Too Far Away Thy Grave to See

(All pictures and text by Ken Wright)

From the beginning of recorded history until now, war has been the curse of mankind and by its very nature means the death of many of the combatants and the non-combatants who are caught up in the conflict. Apart from religious or patriotic fanatics, no one who fights for their respective nation wants to die. Most however, are realistic enough to understand that there is a chance they may never return to their loved ones or even to their homeland.

The First World War of 1914-1918 was at the time, supposed to be the war that would end all wars. For the sheer scale of death and destruction, it was horrendous. It was like a sausage machine. Millions of live men were fed into it and it did nothing but churn out corpses in a conflict that was, as history has shown, not the war to end all wars.[1] It was only 21 years later that the world was once again engulfed in conflict. The only lesson mankind has learnt so far from more than two thousand years of killing each other is how to do it more efficiently. Fortunately, a good percentage of the survivor’s experiences and the various battles have been historically recorded. Future generations may, and the emphasis is on ‘may’, learn something from past mistakes and it is hoped, appreciate the sacrifice made by those who fought. But what of those who leave no personal records, books, and letters or are written about in history books. They are just so many grains of sand on a blood stained beach. Who will remember and thank them?

Take for example two men from Australia who volunteered to join the army. There is nothing special about them nor are they related. They were just two ordinary men caught up in a situation not of their making and died thousands of miles apart fighting for King and country and for a cause they believed was a just one. They are both buried far from home, alone and separated in death from those who cared for them. Their passing is possibly representative of all the forgotten victims of that senseless war long ago.

On 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany followed by the Commonwealth of Australia the next day. The British government wasted no time in requesting the Australian government as ‘a great and urgent imperial service’ to seize and destroy the German wireless stations in the south –west Pacific. Included in the message was a request that any territory occupied by this expedition was to be held at the disposal of the Imperial government for the purposes of the peace settlement. [2] The New Zealand government was also asked for action against the Germans on Samoa. Great Britain wanted the wireless installations to be destroyed because they were used by the German East Asian Cruiser Squadron of Vice Admiral Maximillan von Spee which threatened merchant shipping in the region.

Both the Australian and New Zealand governments agreed to the British request and in Australia, moves were made to raise a special mixed force to be known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force. The AN&MEF was assembled under Colonel J.G.Legge and comprised one battalion of infantry (1000 men) enlisted in Sydney plus 500 naval reservists and ex-sailors who would serve as infantry. Another battalion of militia from northern Queensland which had been hurriedly dispatched to garrison Thursday Island contributed 500 volunteers to the force.

Under the command of Colonel William Holmes, the AN&MEF departed Sydney aboard the liner Berrima and stopped at Palm Island off Townsville until the New Zealand force, escorted by the battle cruiser His Majesty's Australian Ship Australia, the cruiser HMAS Melbourne and the French Cruiser Montcalm, occupied Samoa on 30 August. The AN&MEF then moved to Port Moresby where they met the Queensland contingent aboard the transport Kanowna. The force then sailed for German occupied New Guinea on 7 September but the Kanowna was left behind when her stokers refused to work.

Off the eastern tip of New Guinea, the Berrima rendezvoused with Australia and the light cruiser HMAS Sydney plus some destroyers. Melbourne had been detached to destroy the wireless station on Nauru. The task force reached Rabaul on 11 September and found the port free of German forces. Sydney and the destroyer HMAS Warrego landed small parties of naval reservists at the settlements of Kabakaul and Herbertshöhe south west of Rabaul. These parties were reinforced firstly by sailors from Warrego and later by infantry from Berrima. In fighting at Kabakaul the first Australian fatality from enemy action is believed to be Able Seaman W.G.V. Williams who was mortally wounded and died the same day. By nightfall, the small German garrison had surrendered.

At nightfall on 12 September, the Berrima landed the AN&MEF infantry battalion at Rabaul. The following afternoon, despite the fact that the German governor had not surrendered the territory; a ceremony was carried out to signal the occupation of New Britain. The German administration had withdrawn inland to Toma and at dawn the next day, HMAS Encounter bombarded a ridge near the town, while half a battalion advanced towards the town supported by an artillery piece.

The Germans wisely decided to start surrender negotiations and the two sides came to a mutual gentleman’s agreement on 21 September. All German military resistance in New Guinea would cease and the colony’s governor, Dr Haber could return to Germany. In addition, all German civilians could remain as long as they swore an oath of neutrality. Those who refused would be transported to Australia where they could freely travel back to Germany. The remaining German outposts were occupied by the Australian forces over the next two months. Australia’s first submarines, the AE1 and AE2 also took part in the operation but AE1 mysteriously disappeared while on patrol.2 To date it is not known where or why the submarine was lost.

The initial AN&MEF force was to be augmented by 3 Battalion Tropical Force. The call for volunteers in the various states for service in the tropics was answered in a few days by 4 or 5 times the number required. Many had served in the 1899-1902 Boer War in South Africa and wore their campaign ribbons. One successful volunteer was Joseph Read. He had come to Australia from London to start a new life and took on a plasterer’s trade after his arrival in South Australia. He successfully enlisted on 31 October 1914 in the AN&MEF and became Private Joseph Read, Number 118, D Company, 3 Battalion. He was one of those who had served with the British Army in the Boer War with the 2nd Battalion Dorset shire Regiment between 1901-1902.

By 13 November, the full quotas from the States had been assembled and sent to Liverpool Army Camp outside Sydney with Major F.W. Toll as their Commanding Officer. With the barest of training, the members of 3rd Battalion embarked from Sydney 28 November aboard His Majesty's Australian Transport SS Eastern bound for Rabaul. The other German possessions named by the British Government were gradually occupied by the Australian forces. New Ireland, the Admiralty Islands, Western Islands, Bougainville, New Guinea, Nauru and the German Solomon Islands were all brought under Australian administration until their future could be decided after the war. [3]

Private Read was a member of the occupying forces possibly stationed on Bougainville as his location is not mentioned in his service record. It was on 11 February 1915, he died not from the effects of a German bullet or an unfortunate accident but from the bite of a mosquito. He had contracted Blackwater fever which was a very dangerous complication of malignant malaria. He was buried in the Kieta Cemetery, Bougainville,having served his country for a little over three months and leaving his brother Arthur in Australia as the only one to mourn his passing.

The First World War of 1914-1918 was at the time, supposed to be the war that would end all wars. For the sheer scale of death and destruction, it was horrendous. It was like a sausage machine. Millions of live men were fed into it and it did nothing but churn out corpses in a conflict that was, as history has shown, not the war to end all wars.[1] It was only 21 years later that the world was once again engulfed in conflict. The only lesson mankind has learnt so far from more than two thousand years of killing each other is how to do it more efficiently. Fortunately, a good percentage of the survivor’s experiences and the various battles have been historically recorded. Future generations may, and the emphasis is on ‘may’, learn something from past mistakes and it is hoped, appreciate the sacrifice made by those who fought. But what of those who leave no personal records, books, and letters or are written about in history books. They are just so many grains of sand on a blood stained beach. Who will remember and thank them?

Take for example two men from Australia who volunteered to join the army. There is nothing special about them nor are they related. They were just two ordinary men caught up in a situation not of their making and died thousands of miles apart fighting for King and country and for a cause they believed was a just one. They are both buried far from home, alone and separated in death from those who cared for them. Their passing is possibly representative of all the forgotten victims of that senseless war long ago.

On 4 August 1914, Great Britain declared war on Germany followed by the Commonwealth of Australia the next day. The British government wasted no time in requesting the Australian government as ‘a great and urgent imperial service’ to seize and destroy the German wireless stations in the south –west Pacific. Included in the message was a request that any territory occupied by this expedition was to be held at the disposal of the Imperial government for the purposes of the peace settlement. [2] The New Zealand government was also asked for action against the Germans on Samoa. Great Britain wanted the wireless installations to be destroyed because they were used by the German East Asian Cruiser Squadron of Vice Admiral Maximillan von Spee which threatened merchant shipping in the region.

Both the Australian and New Zealand governments agreed to the British request and in Australia, moves were made to raise a special mixed force to be known as the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force. The AN&MEF was assembled under Colonel J.G.Legge and comprised one battalion of infantry (1000 men) enlisted in Sydney plus 500 naval reservists and ex-sailors who would serve as infantry. Another battalion of militia from northern Queensland which had been hurriedly dispatched to garrison Thursday Island contributed 500 volunteers to the force.

Under the command of Colonel William Holmes, the AN&MEF departed Sydney aboard the liner Berrima and stopped at Palm Island off Townsville until the New Zealand force, escorted by the battle cruiser His Majesty's Australian Ship Australia, the cruiser HMAS Melbourne and the French Cruiser Montcalm, occupied Samoa on 30 August. The AN&MEF then moved to Port Moresby where they met the Queensland contingent aboard the transport Kanowna. The force then sailed for German occupied New Guinea on 7 September but the Kanowna was left behind when her stokers refused to work.

Off the eastern tip of New Guinea, the Berrima rendezvoused with Australia and the light cruiser HMAS Sydney plus some destroyers. Melbourne had been detached to destroy the wireless station on Nauru. The task force reached Rabaul on 11 September and found the port free of German forces. Sydney and the destroyer HMAS Warrego landed small parties of naval reservists at the settlements of Kabakaul and Herbertshöhe south west of Rabaul. These parties were reinforced firstly by sailors from Warrego and later by infantry from Berrima. In fighting at Kabakaul the first Australian fatality from enemy action is believed to be Able Seaman W.G.V. Williams who was mortally wounded and died the same day. By nightfall, the small German garrison had surrendered.

At nightfall on 12 September, the Berrima landed the AN&MEF infantry battalion at Rabaul. The following afternoon, despite the fact that the German governor had not surrendered the territory; a ceremony was carried out to signal the occupation of New Britain. The German administration had withdrawn inland to Toma and at dawn the next day, HMAS Encounter bombarded a ridge near the town, while half a battalion advanced towards the town supported by an artillery piece.

The Germans wisely decided to start surrender negotiations and the two sides came to a mutual gentleman’s agreement on 21 September. All German military resistance in New Guinea would cease and the colony’s governor, Dr Haber could return to Germany. In addition, all German civilians could remain as long as they swore an oath of neutrality. Those who refused would be transported to Australia where they could freely travel back to Germany. The remaining German outposts were occupied by the Australian forces over the next two months. Australia’s first submarines, the AE1 and AE2 also took part in the operation but AE1 mysteriously disappeared while on patrol.2 To date it is not known where or why the submarine was lost.

The initial AN&MEF force was to be augmented by 3 Battalion Tropical Force. The call for volunteers in the various states for service in the tropics was answered in a few days by 4 or 5 times the number required. Many had served in the 1899-1902 Boer War in South Africa and wore their campaign ribbons. One successful volunteer was Joseph Read. He had come to Australia from London to start a new life and took on a plasterer’s trade after his arrival in South Australia. He successfully enlisted on 31 October 1914 in the AN&MEF and became Private Joseph Read, Number 118, D Company, 3 Battalion. He was one of those who had served with the British Army in the Boer War with the 2nd Battalion Dorset shire Regiment between 1901-1902.

By 13 November, the full quotas from the States had been assembled and sent to Liverpool Army Camp outside Sydney with Major F.W. Toll as their Commanding Officer. With the barest of training, the members of 3rd Battalion embarked from Sydney 28 November aboard His Majesty's Australian Transport SS Eastern bound for Rabaul. The other German possessions named by the British Government were gradually occupied by the Australian forces. New Ireland, the Admiralty Islands, Western Islands, Bougainville, New Guinea, Nauru and the German Solomon Islands were all brought under Australian administration until their future could be decided after the war. [3]

Private Read was a member of the occupying forces possibly stationed on Bougainville as his location is not mentioned in his service record. It was on 11 February 1915, he died not from the effects of a German bullet or an unfortunate accident but from the bite of a mosquito. He had contracted Blackwater fever which was a very dangerous complication of malignant malaria. He was buried in the Kieta Cemetery, Bougainville,having served his country for a little over three months and leaving his brother Arthur in Australia as the only one to mourn his passing.

Private Read's grave in Kieta Cemetery, Bougainville, Papua New Guinea

The second man, John Thomas Holdroyd, left York in England also for a new life in Australia, and worked as a miner living with his wife Lara in Hicksborough in Victoria. He enlisted in the Australian Army on 1 February 1916 and became Private Holdroyd, Number 5370, 14 Reinforcements, 22 Infantry Battalion Australian Imperial Forces. After basic training he and his battalion sailed for Plymouth-England aboard HMAT Themistocles from Melbourne 28 July 1916, and then onto France and the terrible battles on the Western Front.

The 22nd Battalion had been originally formed in March 1915 at Broadmeadows, an outer suburb of Melbourne, and became part of the 6th Brigade, 2nd Division. The men of the battalion embarked for Egypt early May and first saw action in the beginning of September during the disastrous Gallipoli campaign on the Turkish coast. They were evacuated along with the rest of the British forces in December when it was decided the campaign was un-winnable. It was not until March 1916 when the battalion left for France and their arrival at the Western Front, were they were to become part of the 1st Anzac Corps and experience action in the reserve breastwork near Fleurbaix. The battalion fought again at Pozieres as part of the massive British offensive on the Somme.

It was during the months of September/October they were moved to the Ypres sector then back to the Somme for the winter. Private Holdroyd joined his battalion in the field on 4th December and spent the first five months of 1917 with his battalion engaged in bloody trench warfare from Bullecourt to Broodseinde in Flanders. The 1st Anzac Corps was eventually withdrawn from the line to rest and refit during to May

The British Allied Commander General Douglas Haig planned a new offensive around 20 September against Westhoek Ridge and chose for the task the four Australian divisions of the 1st Anzac Corps which by now had spent the past three months in the rear areas in Flanders. They had been enjoying what was possibly the finest rest ever given to British Empire troops in France. The depleted ranks had been filled by reinforcements and the training was said to have reached the highest peak attained by the A.I.F during the war.

On 16 September after a night march through Ypres and out along a road that was shelled by the Germans quite often, the 1st and 2nd divisions took over the section of the battle front on the main ridge at Glencorse Wood and a low spur to the north of it at Westhoek.

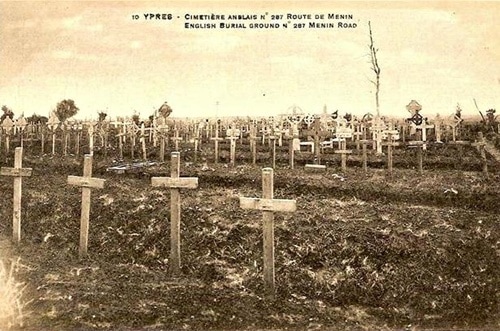

Private John Thomas Holdroyd never made it to his battalion’s allocated section of the front. His service records state he died of wounds on 16 September 1917 and that additional details of his death were unavailable at the time. Without further information, it is only conjecture, but he may have been wounded by shellfire on the road enroute from Ypres to Glencorse Wood. Private Holdroyd is buried in the Menin Road South Military Cemetery Ypres, Belgium.[4]

These two men, Privates Read and Holdroyd were fortunate in as much as they at least have a final resting place with a headstone, a place of reverence where a casual visitor may pause for a moment and if inclined with head bowed, say ‘thank you’. For the unknown thousands from that terrible war who have no known grave there are of course official records and monuments to their passing but they will never have someone pay their respects by their individual gravesides. To the religious, they are, ‘known only unto God’, or they are destined to remain forever forgotten.

Read’s headstone at Kieta on Bougainville has no epitaph, but Holdroyd’s head stone at Ypres in Belgium, thousands of miles apart and so far from their adopted country, has a fitting description that is suitable for them both. ‘Too far away, thy grave to see, but not too far to think of thee’.

The 22nd Battalion had been originally formed in March 1915 at Broadmeadows, an outer suburb of Melbourne, and became part of the 6th Brigade, 2nd Division. The men of the battalion embarked for Egypt early May and first saw action in the beginning of September during the disastrous Gallipoli campaign on the Turkish coast. They were evacuated along with the rest of the British forces in December when it was decided the campaign was un-winnable. It was not until March 1916 when the battalion left for France and their arrival at the Western Front, were they were to become part of the 1st Anzac Corps and experience action in the reserve breastwork near Fleurbaix. The battalion fought again at Pozieres as part of the massive British offensive on the Somme.

It was during the months of September/October they were moved to the Ypres sector then back to the Somme for the winter. Private Holdroyd joined his battalion in the field on 4th December and spent the first five months of 1917 with his battalion engaged in bloody trench warfare from Bullecourt to Broodseinde in Flanders. The 1st Anzac Corps was eventually withdrawn from the line to rest and refit during to May

The British Allied Commander General Douglas Haig planned a new offensive around 20 September against Westhoek Ridge and chose for the task the four Australian divisions of the 1st Anzac Corps which by now had spent the past three months in the rear areas in Flanders. They had been enjoying what was possibly the finest rest ever given to British Empire troops in France. The depleted ranks had been filled by reinforcements and the training was said to have reached the highest peak attained by the A.I.F during the war.

On 16 September after a night march through Ypres and out along a road that was shelled by the Germans quite often, the 1st and 2nd divisions took over the section of the battle front on the main ridge at Glencorse Wood and a low spur to the north of it at Westhoek.

Private John Thomas Holdroyd never made it to his battalion’s allocated section of the front. His service records state he died of wounds on 16 September 1917 and that additional details of his death were unavailable at the time. Without further information, it is only conjecture, but he may have been wounded by shellfire on the road enroute from Ypres to Glencorse Wood. Private Holdroyd is buried in the Menin Road South Military Cemetery Ypres, Belgium.[4]

These two men, Privates Read and Holdroyd were fortunate in as much as they at least have a final resting place with a headstone, a place of reverence where a casual visitor may pause for a moment and if inclined with head bowed, say ‘thank you’. For the unknown thousands from that terrible war who have no known grave there are of course official records and monuments to their passing but they will never have someone pay their respects by their individual gravesides. To the religious, they are, ‘known only unto God’, or they are destined to remain forever forgotten.

Read’s headstone at Kieta on Bougainville has no epitaph, but Holdroyd’s head stone at Ypres in Belgium, thousands of miles apart and so far from their adopted country, has a fitting description that is suitable for them both. ‘Too far away, thy grave to see, but not too far to think of thee’.

Footnotes.

1- The famous novelist and poet Robert Graves originally wrote the description of the world of trench stalemate the First World War was to become.

2- Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 Vol.X. The Australians at Rabaul, S.S. Mackenzie, 1927.

3- The League of Nations placed the territory together with the rest of German New Guinea under Australian mandate in 1920.

4- Plot 1 Row Q Grave 38.

© Ken Wright. 2009.

1- The famous novelist and poet Robert Graves originally wrote the description of the world of trench stalemate the First World War was to become.

2- Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918 Vol.X. The Australians at Rabaul, S.S. Mackenzie, 1927.

3- The League of Nations placed the territory together with the rest of German New Guinea under Australian mandate in 1920.

4- Plot 1 Row Q Grave 38.

© Ken Wright. 2009.