Berks Cemetery Extension

Percy Charles Richards M. M.

2425 Private

Percy Charles Richards, M. M.

39th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

6th December 1917, aged 34.

Plot II. C. 36.

Son of Louisa Richards, of Rokewood Junction, Victoria, Australia, and the late William Richards.

Picture courtesy of Rod Martin

Percy Charles Richards, M. M.

39th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

6th December 1917, aged 34.

Plot II. C. 36.

Son of Louisa Richards, of Rokewood Junction, Victoria, Australia, and the late William Richards.

Picture courtesy of Rod Martin

Percy Charles Richards M.M.

5th November 1882 - 6th December 1917

(By Rod Martin)

EXPLANATORY NOTE

As a soldier in the Australian Imperial Force, Percy belonged to a number of different units, each proportionally larger in size than the next. First and foremost, he was a member of F Company, 39 Battalion (between 700 and 800 men). This was the unit to which he was assigned while he was completing his training. His commanding officer in 39 Battalion was Lieutenant-Colonel R.O. Henderson.

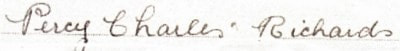

39 Battalion, in turn, was one of four battalions in 10 Brigade. This unit was commanded by Brigadier-General Walter Ramsay McNicoll. It was McNicoll who approved the award of the Military Medal to Percy in 1917.

10 Brigade was part of 3 Division, commanded by Major-General John Monash. The division was composed of four brigades.

3 Division was, in its turn, part of II Anzac Corps, commanded by British Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Godley. The corps comprised three divisions. (The two Anzac corps were later merged to form the Australian Corps, under a promoted Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash.)

Finally, II Anzac Corps was attached to the British Second Army, commanded by General Sir Herbert Plumer.

Where possible, I have referred to the deeds of 39 Battalion, as one can assume that, whatever actions it undertook, Percy was involved in them. When such referral is not possible because of lack of information, I have referred to the next largest unit for which information is available.

Rod Martin

Percy Richards was born in the small settlement of Rokewood Junction, in western Victoria, in 1882. Family records and the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages indicate that it was on 5 November that year. That would have made him thirty-three years and eight months old when he joined the army in July 1916. While enlisting, however, Percy stated in writing on no less than three separate occasions that he was aged thirty-three years and six months – which would have meant that he was born in either January or February 1883. Unfortunately, confirmatory church baptismal records are unavailable, having been destroyed in a bushfire in 1944. So the confusion remains, and the mystery is deepened by the age listed on his gravestone (p. 31).

Percy was the sixth son and seventh child of William and Louisa Richards. Family memories have it that William was a gold miner, born at the Cape of Good Hope in 1845 to Frederick and Charlotte Richards, and brought to Australia with the rest of his family in 1853. Given that the family arrived in Victoria just a year before the Eureka Rebellion, it is likely that Frederick came in search of gold. The family moved several times in their first few years in the colony, as evidenced by the family records, probably following a string of new gold discoveries. A daughter named Charlotte was born in Emerald in 1854 (gold was discovered in Emerald in the 1850s), a son – John – in Raglan in 1857, two children – Sarah and Eliza – at Rokewood in the early 1860s, and another daughter, Louisa, at nearby Pitfield in 1865.

The evidence indicates that William and his wife Louisa, as well as his parents Frederick and Charlotte, were back at Rokewood Junction on a farm by the start of the 1880s.

The family’s information is that the men were still searching for gold, but were increasingly relying upon the farm for their livelihood. Percy was born at Rokewood Junction in 1882 and Charlotte died there in 1888. Frederick also passed away there in 1898.

Little is known about Percy’s childhood. Neville Richards, a family member, has reported that he worked on the farm, as would be expected, and became a competent shearer. He also became a keen gold-seeker (he and his brothers actually found quite a sizeable reef in the local area that was mined commercially for several years). With six older brothers, living in a rural area, he is likely to have been involved in plenty of rough and tumble in his early years, and to have grown up as a ‘nuggety’ type with the ability to defend himself when needed. It is remembered that he had the strong hands and thick-set shoulders of a labourer. His recruitment papers indicate that he had scars on his right shin and left knee, perhaps souvenirs of an active boyhood or reminders of some particularly difficult labouring tasks as a young adult. We can presume that, in line with the requirements of the 1872 Education Act, he went to the local school until he was fourteen and then left to seek employment. Exactly what he did and when is not known, but it would appear that he gained no further qualifications (his response to a question on his enlistment application indicates that he had not been an apprentice), working in a variety of positions in more than one place. Family memories suggest that he travelled widely in search of work. At the time of his enlistment in 1916, he was working as a labourer at Lake Boga, near Swan Hill in northern Victoria. A man who saw him die described him as a “bushman”, and said he knew him in Kerang before he enlisted. One could speculate that he may have been a bit of a wanderer, an itinerant. This is suggested by the fact that he cited Rokewood Junction as his permanent address on his enlistment papers, even though he was signing up at Swan Hill. Certainly, he was still single at the age of thirty-three so he had not “settled down”, to use a well-established phrase, and labouring jobs would not have been likely to bring with them much money, status or security.

When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, there was a rush of young men at the recruiting offices, eager to fight for king and country. Percy’s response to this is unknown. It may be that, at the age of thirty-one, he felt that he was a bit old for what was promised to be a young man’s brief adventure, one that should “be over by Christmas”. It may be that he considered the job he was doing at the time to be more important than going off on some imperial venture overseas. He may have had a moral objection to war and killing. There again, he may have tried to enlist, but been rejected. In terms of height, chest size and age, he fitted within the parameters set by the military. However, as Les Carlyon relates, the doctors at this time could pick and choose in a way they would not be able to do later in the war. They were particularly hard on men with bad teeth and flat feet. Perhaps Percy suffered from one of these afflictions. After all, coming from a large family as he did, being in his thirties, and not being wealthy, it is quite possible that he had had a lifetime of dental neglect (his enlistment papers have written across the top of them a date in August 1916 and the statement : ‘dental treatment’). And did years as a youth in the Australian nineteenth century countryside, many of them probably spent running around in bare feet, possibly lead to flat footedness?

As a soldier in the Australian Imperial Force, Percy belonged to a number of different units, each proportionally larger in size than the next. First and foremost, he was a member of F Company, 39 Battalion (between 700 and 800 men). This was the unit to which he was assigned while he was completing his training. His commanding officer in 39 Battalion was Lieutenant-Colonel R.O. Henderson.

39 Battalion, in turn, was one of four battalions in 10 Brigade. This unit was commanded by Brigadier-General Walter Ramsay McNicoll. It was McNicoll who approved the award of the Military Medal to Percy in 1917.

10 Brigade was part of 3 Division, commanded by Major-General John Monash. The division was composed of four brigades.

3 Division was, in its turn, part of II Anzac Corps, commanded by British Lieutenant-General Sir Alexander Godley. The corps comprised three divisions. (The two Anzac corps were later merged to form the Australian Corps, under a promoted Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash.)

Finally, II Anzac Corps was attached to the British Second Army, commanded by General Sir Herbert Plumer.

Where possible, I have referred to the deeds of 39 Battalion, as one can assume that, whatever actions it undertook, Percy was involved in them. When such referral is not possible because of lack of information, I have referred to the next largest unit for which information is available.

Rod Martin

Percy Richards was born in the small settlement of Rokewood Junction, in western Victoria, in 1882. Family records and the Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages indicate that it was on 5 November that year. That would have made him thirty-three years and eight months old when he joined the army in July 1916. While enlisting, however, Percy stated in writing on no less than three separate occasions that he was aged thirty-three years and six months – which would have meant that he was born in either January or February 1883. Unfortunately, confirmatory church baptismal records are unavailable, having been destroyed in a bushfire in 1944. So the confusion remains, and the mystery is deepened by the age listed on his gravestone (p. 31).

Percy was the sixth son and seventh child of William and Louisa Richards. Family memories have it that William was a gold miner, born at the Cape of Good Hope in 1845 to Frederick and Charlotte Richards, and brought to Australia with the rest of his family in 1853. Given that the family arrived in Victoria just a year before the Eureka Rebellion, it is likely that Frederick came in search of gold. The family moved several times in their first few years in the colony, as evidenced by the family records, probably following a string of new gold discoveries. A daughter named Charlotte was born in Emerald in 1854 (gold was discovered in Emerald in the 1850s), a son – John – in Raglan in 1857, two children – Sarah and Eliza – at Rokewood in the early 1860s, and another daughter, Louisa, at nearby Pitfield in 1865.

The evidence indicates that William and his wife Louisa, as well as his parents Frederick and Charlotte, were back at Rokewood Junction on a farm by the start of the 1880s.

The family’s information is that the men were still searching for gold, but were increasingly relying upon the farm for their livelihood. Percy was born at Rokewood Junction in 1882 and Charlotte died there in 1888. Frederick also passed away there in 1898.

Little is known about Percy’s childhood. Neville Richards, a family member, has reported that he worked on the farm, as would be expected, and became a competent shearer. He also became a keen gold-seeker (he and his brothers actually found quite a sizeable reef in the local area that was mined commercially for several years). With six older brothers, living in a rural area, he is likely to have been involved in plenty of rough and tumble in his early years, and to have grown up as a ‘nuggety’ type with the ability to defend himself when needed. It is remembered that he had the strong hands and thick-set shoulders of a labourer. His recruitment papers indicate that he had scars on his right shin and left knee, perhaps souvenirs of an active boyhood or reminders of some particularly difficult labouring tasks as a young adult. We can presume that, in line with the requirements of the 1872 Education Act, he went to the local school until he was fourteen and then left to seek employment. Exactly what he did and when is not known, but it would appear that he gained no further qualifications (his response to a question on his enlistment application indicates that he had not been an apprentice), working in a variety of positions in more than one place. Family memories suggest that he travelled widely in search of work. At the time of his enlistment in 1916, he was working as a labourer at Lake Boga, near Swan Hill in northern Victoria. A man who saw him die described him as a “bushman”, and said he knew him in Kerang before he enlisted. One could speculate that he may have been a bit of a wanderer, an itinerant. This is suggested by the fact that he cited Rokewood Junction as his permanent address on his enlistment papers, even though he was signing up at Swan Hill. Certainly, he was still single at the age of thirty-three so he had not “settled down”, to use a well-established phrase, and labouring jobs would not have been likely to bring with them much money, status or security.

When war broke out in Europe in August 1914, there was a rush of young men at the recruiting offices, eager to fight for king and country. Percy’s response to this is unknown. It may be that, at the age of thirty-one, he felt that he was a bit old for what was promised to be a young man’s brief adventure, one that should “be over by Christmas”. It may be that he considered the job he was doing at the time to be more important than going off on some imperial venture overseas. He may have had a moral objection to war and killing. There again, he may have tried to enlist, but been rejected. In terms of height, chest size and age, he fitted within the parameters set by the military. However, as Les Carlyon relates, the doctors at this time could pick and choose in a way they would not be able to do later in the war. They were particularly hard on men with bad teeth and flat feet. Perhaps Percy suffered from one of these afflictions. After all, coming from a large family as he did, being in his thirties, and not being wealthy, it is quite possible that he had had a lifetime of dental neglect (his enlistment papers have written across the top of them a date in August 1916 and the statement : ‘dental treatment’). And did years as a youth in the Australian nineteenth century countryside, many of them probably spent running around in bare feet, possibly lead to flat footedness?

By Christmas 1914, 52 000 men had enlisted in what became known as the Australian Imperial Force (AIF), and 30 000 of them had departed for the Middle East in the first convoy on 1 November. As Carlyon puts it, enlistments were still averaging about 8 000 a month for the first four months of 1915. But then came Gallipoli. At first, enlistments soared, reaching a peak of 36 575 in July of that year. However, as the casualty lists in the newspapers mounted, numbers dropped off and had declined to about 6 000 a month by July 1916. By that time, the Australian forces were stationed on the Western Front in France, involved in the Battle of the Somme and the butchery of associated confrontations at Fromelles and Pozières.

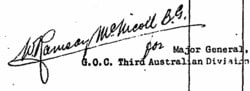

What caused Percy to change his mind and enlist in the armed forces in August of that year is, again, unknown. We know that, by that month, enlistments had dropped to a new and alarming low of 4 144 and that the British War Office called for urgent reinforcements to rebuild the five Australian divisions in France. The aim was for 32 500 extra men by the end of September. A massive recruitment campaign was launched, and it may be that Percy decided that he could no longer hold off, that it was his duty to support those other men in what had become a protracted and desperate struggle the length and breadth of the Western Front. As the official war historian, Charles Bean, writes, the “members [of what became known as the Australian 3 Division] volunteered in no spirit of adventure (the “adventurers” having rushed to the Ist Division), but from sober determination to see the war through.” It may also be the case that, along with many other men, Percy was subjected to moral pressure here in Australia. Stark propaganda of the type seen below became increasingly common “as recruiters tried to convince Australians that it really was their war”. In addition, the long-established and often indiscriminate practice of sending white feathers (symbols of cowardice) to men who had not enlisted was becoming increasingly popular and was used, with devastating results in some cases.

Whatever the reason, Percy volunteered by signing an attestation paper at Swan Hill on 28 July 1916 and stated his age as being thirty-three years and six months. His medical examination details state that he was five feet seven and a half inches tall (approximately 169 centimetres) and 146 pounds in weight (approximately sixty-six kilograms), with a medium complexion, his eyes being grey and his hair brown.

The attestation paper indicates that he was then transferred to Melbourne and formally inducted into the military forces on 4 August, exactly two years after the outbreak of the First World War. At that time, he underwent another medical examination. From there, it is likely that he travelled to a base camp at Ballarat, as did many of the recruits from central and northern Victoria. Evidence of this is the fact that he was disciplined for going absent without leave in Ballarat for one day on 4 September (for which he was fined the day’s pay). While at the camp, he was provided with basic military training for two months or so. On 22 August, he was given the regimental number 2425 and allocated to F Company, part of the Fourth Reinforcements for 39 Battalion AIF.

Along with 150 new compatriots, Percy moved to a base at Royal Park in Melbourne on 5 October and then sailed for Europe on 20 October on the troop transport HMAT Port Lincoln.

What caused Percy to change his mind and enlist in the armed forces in August of that year is, again, unknown. We know that, by that month, enlistments had dropped to a new and alarming low of 4 144 and that the British War Office called for urgent reinforcements to rebuild the five Australian divisions in France. The aim was for 32 500 extra men by the end of September. A massive recruitment campaign was launched, and it may be that Percy decided that he could no longer hold off, that it was his duty to support those other men in what had become a protracted and desperate struggle the length and breadth of the Western Front. As the official war historian, Charles Bean, writes, the “members [of what became known as the Australian 3 Division] volunteered in no spirit of adventure (the “adventurers” having rushed to the Ist Division), but from sober determination to see the war through.” It may also be the case that, along with many other men, Percy was subjected to moral pressure here in Australia. Stark propaganda of the type seen below became increasingly common “as recruiters tried to convince Australians that it really was their war”. In addition, the long-established and often indiscriminate practice of sending white feathers (symbols of cowardice) to men who had not enlisted was becoming increasingly popular and was used, with devastating results in some cases.

Whatever the reason, Percy volunteered by signing an attestation paper at Swan Hill on 28 July 1916 and stated his age as being thirty-three years and six months. His medical examination details state that he was five feet seven and a half inches tall (approximately 169 centimetres) and 146 pounds in weight (approximately sixty-six kilograms), with a medium complexion, his eyes being grey and his hair brown.

The attestation paper indicates that he was then transferred to Melbourne and formally inducted into the military forces on 4 August, exactly two years after the outbreak of the First World War. At that time, he underwent another medical examination. From there, it is likely that he travelled to a base camp at Ballarat, as did many of the recruits from central and northern Victoria. Evidence of this is the fact that he was disciplined for going absent without leave in Ballarat for one day on 4 September (for which he was fined the day’s pay). While at the camp, he was provided with basic military training for two months or so. On 22 August, he was given the regimental number 2425 and allocated to F Company, part of the Fourth Reinforcements for 39 Battalion AIF.

Along with 150 new compatriots, Percy moved to a base at Royal Park in Melbourne on 5 October and then sailed for Europe on 20 October on the troop transport HMAT Port Lincoln.

The ship crossed the Indian Ocean to the Cape of Good Hope, and then sailed north along the west coast of Africa towards Europe. Percy’s statement of service indicates that he transferred to another vessel at Sierra Leone on 2 December. He and his compatriots finally docked in Plymouth on the south coast of England on 9 January 1917. Once on shore, Percy was taken to the training camp at Durrington in Wiltshire, not far from Salisbury Plain, arriving on 10 January. There he joined 10 Training Battalion and received intensive instruction on the finer points of trench warfare from men who had survived on the Western Front in France and Belgium.

Charles Bean tells us that these later recruits, who were destined to form part of 3 Australian Division, were treated with kid gloves by the military. It was the opinion of the overall Australian commander, General Birdwood, that the Australian government, having itself organized this division, had to take a special interest in it. Not for 39 Battalion the experience of the men of 4 and 5 Divisions who had been “forged out of half-veteran material in the dust and sweat of Egypt and then flung into battle like a learner of swimming thrown into deep water”. Instead, its members had the intensive training on Salisbury Plain and then, on 25 April 1917, the third Anzac Day (as it was called by then), Percy and the Fourth Reinforcements were transported to the port of Folkstone in Kent. From there, they sailed across the Straits of Dover to France, probably arriving at the port of Boulogne. After that, they were conveyed to billets in Armentières, a French town not far from the front, deliberately allowed to acclimatize, and issued with equipment such as steel helmets and gas respirators. The area around Armentières was the quietest corner of the British Front. It was known as the “nursery sector”, where new or exhausted divisions were stationed to enjoy a relatively quiet period. When they were selected to go to the front, the troops were marched to their assigned sectors and stationed in reserve trenches, waiting to relieve exhausted and shell-shocked men after their spell in the front line.

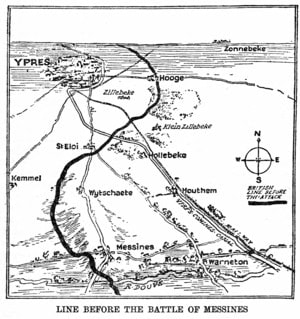

For Percy, this happened around 13 May. On that day he marched about eight kilometres, probably saw plenty of the red poppies for which Flanders is famous, and joined the rest of the battalion, which was attached to the Australian 3 Division, commanded by Major-General John Monash. In May 1917, 3 Division was stationed at Messines in Belgian Flanders, close to the French border and Armentières, and at the far southern end of what had been known since 1915 as the Ypres Front. By this time, the war on the Western Front had been going on for almost three years. Despite incredibly bloody conflicts such as the First and Second Battles of Ypres (1914, 1915), the Somme in 1916 and Arras and Bullecourt in April 1917, the Allied forces had failed to break the stalemate and trench warfare that had developed along the front after September 1914. The Germans were well-entrenched, even more so after they tactically retreated to the stronger fortifications of the so-called Hindenburg Line in February 1917. When Percy arrived at the front, a new offensive in Flanders was being prepared. It would officially be known as the Third Battle of Ypres, but more incorrectly and infamously as the Battle of Passchendaele, after the name of the town that would be its final target. Monash’s 3 Division was going to be a part of the opening encounter – at Messines.

3 Division is described by Bean as being the ‘baby’ of the AIF, untried so far in major engagements. Because of its newness, its appearance and proficiency in exercises, plus the belief that it was the darling of the Australian Department of Defence, the division was often referred to derisively by other units as the ‘neutrals’, the ‘Lark Hill Lancers’ (after the name of their training camp at Durrington) or, most generally, as the ‘Eggs-a-cook’* on account of its oval shoulder patches.

* A term picked up in Egypt by troops. It was evidently the cry of Egyptian sellers of boiled eggs.

Monash added to this apparent uniqueness by ordering the men to distinguish themselves further by wearing their hat brims flat, instead of looped as was the case in the rest of the AIF. According to Bean, the troops wanted desperately to be accepted as comrades by the rest of the army, not to be seen as something separate and distinct, subject to resultant ridicule. They were not happy about their hats!

As part of this ‘new’ force, Percy and the Fourth Reinforcements appeared at Messines just in time to be involved in the action planned for 7 June. The intention of the British commander-in-chief, Sir Douglas Haig, was to “turn the German flank from the Ypres salient, occupy the Belgian coast and capture the enemy’s submarine pens [at Ostend and Zeebrugge]”. Haig argued that such a move would place enormous pressure on the Germans, who would be forced to transfer extra forces into the Ypres area to avoid losing it, thus taking pressure off the beleaguered French Army further south, already suffering mutinies. In addition, capture of the submarine pens would remove much of the threat to allied convoys in the Atlantic, involved in transporting troops, equipment and food from North America. Moreover, he argued, German morale, already crumbling, would be devastated by the inevitable losses in Flanders.

Charles Bean tells us that these later recruits, who were destined to form part of 3 Australian Division, were treated with kid gloves by the military. It was the opinion of the overall Australian commander, General Birdwood, that the Australian government, having itself organized this division, had to take a special interest in it. Not for 39 Battalion the experience of the men of 4 and 5 Divisions who had been “forged out of half-veteran material in the dust and sweat of Egypt and then flung into battle like a learner of swimming thrown into deep water”. Instead, its members had the intensive training on Salisbury Plain and then, on 25 April 1917, the third Anzac Day (as it was called by then), Percy and the Fourth Reinforcements were transported to the port of Folkstone in Kent. From there, they sailed across the Straits of Dover to France, probably arriving at the port of Boulogne. After that, they were conveyed to billets in Armentières, a French town not far from the front, deliberately allowed to acclimatize, and issued with equipment such as steel helmets and gas respirators. The area around Armentières was the quietest corner of the British Front. It was known as the “nursery sector”, where new or exhausted divisions were stationed to enjoy a relatively quiet period. When they were selected to go to the front, the troops were marched to their assigned sectors and stationed in reserve trenches, waiting to relieve exhausted and shell-shocked men after their spell in the front line.

For Percy, this happened around 13 May. On that day he marched about eight kilometres, probably saw plenty of the red poppies for which Flanders is famous, and joined the rest of the battalion, which was attached to the Australian 3 Division, commanded by Major-General John Monash. In May 1917, 3 Division was stationed at Messines in Belgian Flanders, close to the French border and Armentières, and at the far southern end of what had been known since 1915 as the Ypres Front. By this time, the war on the Western Front had been going on for almost three years. Despite incredibly bloody conflicts such as the First and Second Battles of Ypres (1914, 1915), the Somme in 1916 and Arras and Bullecourt in April 1917, the Allied forces had failed to break the stalemate and trench warfare that had developed along the front after September 1914. The Germans were well-entrenched, even more so after they tactically retreated to the stronger fortifications of the so-called Hindenburg Line in February 1917. When Percy arrived at the front, a new offensive in Flanders was being prepared. It would officially be known as the Third Battle of Ypres, but more incorrectly and infamously as the Battle of Passchendaele, after the name of the town that would be its final target. Monash’s 3 Division was going to be a part of the opening encounter – at Messines.

3 Division is described by Bean as being the ‘baby’ of the AIF, untried so far in major engagements. Because of its newness, its appearance and proficiency in exercises, plus the belief that it was the darling of the Australian Department of Defence, the division was often referred to derisively by other units as the ‘neutrals’, the ‘Lark Hill Lancers’ (after the name of their training camp at Durrington) or, most generally, as the ‘Eggs-a-cook’* on account of its oval shoulder patches.

* A term picked up in Egypt by troops. It was evidently the cry of Egyptian sellers of boiled eggs.

Monash added to this apparent uniqueness by ordering the men to distinguish themselves further by wearing their hat brims flat, instead of looped as was the case in the rest of the AIF. According to Bean, the troops wanted desperately to be accepted as comrades by the rest of the army, not to be seen as something separate and distinct, subject to resultant ridicule. They were not happy about their hats!

As part of this ‘new’ force, Percy and the Fourth Reinforcements appeared at Messines just in time to be involved in the action planned for 7 June. The intention of the British commander-in-chief, Sir Douglas Haig, was to “turn the German flank from the Ypres salient, occupy the Belgian coast and capture the enemy’s submarine pens [at Ostend and Zeebrugge]”. Haig argued that such a move would place enormous pressure on the Germans, who would be forced to transfer extra forces into the Ypres area to avoid losing it, thus taking pressure off the beleaguered French Army further south, already suffering mutinies. In addition, capture of the submarine pens would remove much of the threat to allied convoys in the Atlantic, involved in transporting troops, equipment and food from North America. Moreover, he argued, German morale, already crumbling, would be devastated by the inevitable losses in Flanders.

The validity of all of these reasons has been disputed and often discounted by historians in the years since. Many believe that Haig’s real purpose in ordering the attack was a desperate effort to win the war before the Americans arrived on the Western Front (they had joined the war in April that year) and seized the glory for themselves. The thought of this, they say, made him hang on grimly at Ypres, despite massive casualties and increasing pressure from all sides to call off the battle. As John Masters argues, What no one, looking back, can understand is why he hoped to succeed. The year before, on the Somme the British Army attacked for four months, suffered 400,000 casualties, and advanced an average of about 3 miles on a front 20 miles wide. nothing had happened and nothing was proposed that would alter this state of affairs-– but the men were now expected to advance 35 miles, the first 15 of them in under two weeks. Whatever Haig's real reasons the Germans had the advantage of holding what high ground there is in Flanders, most notably Messines Ridge, whence they could watch the British preparing for the new offensive. The ridge had long been a problem. Philip Gibbs describes it as “a curse to all our men who have held the Ypres salient – a high barrier against them, behind which the enemy stacked his guns, shooting at them every kind of explosive”. Therefore, it made sense to the British planners to capture this first of all. In doing so, they would remove a large thorn in their side, and then use its natural advantages in a move to sweep the Germans north and then east, hopefully causing the collapse of their army. The British had been planning to capture the ridge since late 1915, taking the bold step of tunnelling beneath it and planting nineteen huge mines at depths of fifteen to thirty metres, immediately below the German trenches. The mines were in place and ready to be blown by 7 June. Their detonation would mark the beginning of the Third Battle of Ypres, hopefully, in Haig’s mind, the decisive conflict of the war. 3 Division, the only Australian force to be involved in the first phase of the battle, was the southernmost of the nine divisions scheduled to attack, and was assigned to capture the southern shoulder of Messines Ridge.

The Germans, of course, had not been sitting idle while all these preparations were going on. They had detected some regrouping of the British divisions, and were curious as to what was happening. As a result, they staged a number of raids on the Australian lines in May, and Percy may have been involved in fending some of them off. In addition, they bombarded the area around Ploegsteert Wood, where 3 Division was based, with gas shells on a number of occasions. However, it was apparent on 7 June that the Germans had no idea about the mining operations and the British plans. Following a preparatory bombardment of the German lines on the ridge during the previous seven days, the mines were detonated at 3.10 am on the morning of 7 June. Approximately 400 000 kilograms of TNT exploded over a period of forty-five seconds. At that stage, it was the largest man-made explosion in history. As Carlyon has described it,

One hundred and thirty miles away Londoners heard it as a distant roar. Fifteen miles to the east German soldiers in Lille ran in panic, fearing an earthquake. Buildings swayed and window glass fell into the streets. Perhaps 10, 000 Germans died as the mines went up, some of them simply atomised. The earth trembled, a wave of hot air ran up the ridge and beyond, black clouds of dust and smoke rolled over the German rear positions and blotted out the light of the sinking moon, craters hundreds of feet wide opened up and the sky rained clods of Flemish clay. The Germans who survived were half-mad and wanted to surrender.

Percy probably heard the explosion. If so, however, it would have been from a distance, and he certainly did not see the results, which are described by Gibbs as being “the most terribly beautiful thing, the most diabolical splendour, I have seen in war”. Another eyewitness, infantryman Edward Lynch, describes it as being like “an enormous black tin hat rising slowly out of the hill”. Six days before this cataclysmic event, Percy had been wounded accidentally in the explosion of an ammunition dump in Ploegsteert Wood, close to the line at Messines Ridge (the explosion may have been set off by the German counter-shelling that occurred after the beginning of the seven-day bombardment). He had received a “slight wound” to the left side of his face while preparing the dump for the upcoming battle. He was probably evacuated to the casualty clearing station at Steenwerck in the rear and then transported by 9 Australian Field Ambulance to a military hospital in Boulogne for treatment and recuperation. He was discharged from the hospital on 11 June and it took him nine days to rejoin his battalion. He arrived back, probably covering the final journey to the front on foot, on 20 June. In consequence, he missed the massive explosion, he missed the advance of 3 Division through Ploegsteert Wood just before the detonation, he missed the German gas bombardment of the wood that occurred at that time, causing at least 500 casualties in 39 Battalion (two-thirds of its total strength) before the formal battle had even started, and he missed the division’s actual attack across no man’s land, and the action that led to the capture of the ridge in just a single day.

By the end of that day, all three British objectives had been achieved and, to use Peter Cochrane’s words, Messines was recorded as one of the great set-piece victories of the war. However, a bitter price had been paid for the three kilometres of territory that had been gained: 6 800 Australian casualties. 306 of them were from 39 Battalion. Some of them were probably Percy’s comrades.

By the time Percy returned to the front on 20 June, the Battle of Messines was over. The Germans had conducted a strategic retreat to more defensible lines on 10 June, and allowed the British forces to occupy their old trenches on the ridge. 10 Brigade, of which 39 Battalion was a part, had been relieved on the night of 8 June after suffering heavy shelling and high casualties. It now sat back near the town of St. Yves, recuperating and licking its wounds, but with the smell of victory in its nostrils.

Spirits would no doubt have been high when Percy arrived back at the lines, doubly so because the initial attack at Ypres, planned for 31 July, would not include any Australians. As Carlyon tells us, they had been scheduled for a long rest. The bravery and daring of the Australian soldiers had been known to the British commanders since the bloody battles of Fromelles and Pozières in the previous year and, increasingly, they had been used as shock troops since that time. The initial attack on Messines Ridge was another such example. As American correspondent Frederick Palmer wrote of Australia in 1917:

I want to see the land that breeds such men. They are free men if ever there were such; free whether they come from town or bush . . . Whenever I saw an Australian I thought: “Here is a very proud, individual man,” but also an Australian, particularly an Australian.

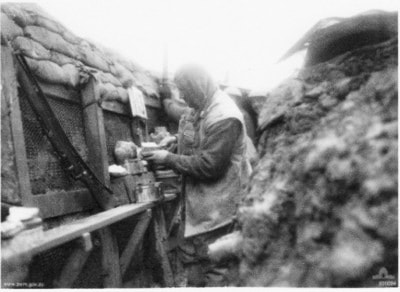

They were now to be given a richly deserved break from the conflict. However, rest or not, the troops were still close to the front line, and to action. As Lynch reflects, “Even the quietest parts of the line take their toll. Even in a quiet innings the wickets fall and players get their despatch to the pavilion, their innings ended”. On 23 June, its rest over, 3 Division took over the captured sector just north of St. Yves and west of the town of Warneton, which was still in German hands. There the troops established three lines of defence.

This work was done under pressure, however. Bean tells us that the German artillery, machine guns and snipers were kept busy in efforts to counteract the Australians’ industriousness. Nevertheless, despite all this hard work and a number of small actions, none of the Australian brigades was close enough to the German line to conduct an effective attack on it. Minor operations were undertaken in the area by units from 3 Division, with some success, but 39 Battalion’s general role at this time was to hold and further secure its section of the line. Percy would have experienced a lot of trench-digging and other construction work. His labouring background probably came in very handy!

The Battle of Passchendaele was a disaster for the British. The successful attack at Messines had warned the Germans that a major offensive at Ypres was imminent, and they reinforced their lines accordingly. And so tardy was the main attack after Messines that they had over a month in which to do it. With nearly a million men on each side, and with the Germans entrenched in their heavily fortified Hindenburg Line, Haig had neither a strategic nor a numerical advantage on the Ypres Front. When the first troops went over the tops of the trenches on 31 July, they would do so against the best advice of military and political planners. One of the biggest problems they would face would be mud, “gluey, intolerable mud”, as Leon Wolff describes it. The ground at Ypres is heavy clay. Water never drains away naturally. What is more, continual bombardments since 1914 had churned up the ground and destroyed the delicate drainage system that had been constructed by farmers many centuries before to make the area arable. When combined with rain, the new preliminary bombardment in 1917 would turn this ground into almost impassable mud. And rain it certainly did, causing British prime minister David Lloyd George to christen the conflict ‘the battle of the mud’.

As A. J. P. Taylor puts it:

Failure was obvious by the end of the first day to everyone except Haig and his immediate circle. The greatest advance was less than half a mile. The main German line was nowhere reached. Rain fell heavily. The ground, turned up by shellfire, turned to mud. Haig sent in tanks. These also vanished in the mud. Imperceptibly Haig changed his tone.

The only purpose of the battle [now] was to kill Germans and shake their morale.

Most war historians agree with Taylor. Captain Basil Liddell Hart describes the conflict as “the gloomiest drama in British military history . . . ‘Passchendaele’ has come to be . . . a synonym for military failure – a name black-bordered in the records of the British Army.” Even writing from a contemporary perspective, Bean called the plan ‘a huge gamble’. “They don’t realise,” he wrote about the British commanders, “how desperately hard it will be to fight down such opposition in the mud, rifles choked, L[ewis] G[uns] out of action, men tired and slow . . . Every step means dragging one foot out of the mud . . . I shall be very surprised if this fight succeeds.” At no stage in the war did Haig go anywhere near the front line, so he never had a real appreciation of the conditions in which the men were fighting. When his chief of staff visited the fighting zone - at Ypres – for the first time in November, he burst into tears and cried: “Good God, did we really send men to fight in that?” By then, however, his grief was all too late. “Passchendaele”, writes John Masters,

Sums up the Great War in itself, because Passchendaele is courage and sacrifice beyond understanding; Passchendaele is the ultimate in acceptance, in discipline; Passchendaele is mud, sleet, lice, mud, noise, jagged steel, horror piled on reeking horror, men and animals torn in pieces, mud seeded with brains and blood, mud heaving with putrifying thousands of fathers, sons and lovers; Passchendaele is appalling muddle, waste to terrify the soul. A German general described it as . . . the greatest martyrdom of the World War.

The Germans, of course, had not been sitting idle while all these preparations were going on. They had detected some regrouping of the British divisions, and were curious as to what was happening. As a result, they staged a number of raids on the Australian lines in May, and Percy may have been involved in fending some of them off. In addition, they bombarded the area around Ploegsteert Wood, where 3 Division was based, with gas shells on a number of occasions. However, it was apparent on 7 June that the Germans had no idea about the mining operations and the British plans. Following a preparatory bombardment of the German lines on the ridge during the previous seven days, the mines were detonated at 3.10 am on the morning of 7 June. Approximately 400 000 kilograms of TNT exploded over a period of forty-five seconds. At that stage, it was the largest man-made explosion in history. As Carlyon has described it,

One hundred and thirty miles away Londoners heard it as a distant roar. Fifteen miles to the east German soldiers in Lille ran in panic, fearing an earthquake. Buildings swayed and window glass fell into the streets. Perhaps 10, 000 Germans died as the mines went up, some of them simply atomised. The earth trembled, a wave of hot air ran up the ridge and beyond, black clouds of dust and smoke rolled over the German rear positions and blotted out the light of the sinking moon, craters hundreds of feet wide opened up and the sky rained clods of Flemish clay. The Germans who survived were half-mad and wanted to surrender.

Percy probably heard the explosion. If so, however, it would have been from a distance, and he certainly did not see the results, which are described by Gibbs as being “the most terribly beautiful thing, the most diabolical splendour, I have seen in war”. Another eyewitness, infantryman Edward Lynch, describes it as being like “an enormous black tin hat rising slowly out of the hill”. Six days before this cataclysmic event, Percy had been wounded accidentally in the explosion of an ammunition dump in Ploegsteert Wood, close to the line at Messines Ridge (the explosion may have been set off by the German counter-shelling that occurred after the beginning of the seven-day bombardment). He had received a “slight wound” to the left side of his face while preparing the dump for the upcoming battle. He was probably evacuated to the casualty clearing station at Steenwerck in the rear and then transported by 9 Australian Field Ambulance to a military hospital in Boulogne for treatment and recuperation. He was discharged from the hospital on 11 June and it took him nine days to rejoin his battalion. He arrived back, probably covering the final journey to the front on foot, on 20 June. In consequence, he missed the massive explosion, he missed the advance of 3 Division through Ploegsteert Wood just before the detonation, he missed the German gas bombardment of the wood that occurred at that time, causing at least 500 casualties in 39 Battalion (two-thirds of its total strength) before the formal battle had even started, and he missed the division’s actual attack across no man’s land, and the action that led to the capture of the ridge in just a single day.

By the end of that day, all three British objectives had been achieved and, to use Peter Cochrane’s words, Messines was recorded as one of the great set-piece victories of the war. However, a bitter price had been paid for the three kilometres of territory that had been gained: 6 800 Australian casualties. 306 of them were from 39 Battalion. Some of them were probably Percy’s comrades.

By the time Percy returned to the front on 20 June, the Battle of Messines was over. The Germans had conducted a strategic retreat to more defensible lines on 10 June, and allowed the British forces to occupy their old trenches on the ridge. 10 Brigade, of which 39 Battalion was a part, had been relieved on the night of 8 June after suffering heavy shelling and high casualties. It now sat back near the town of St. Yves, recuperating and licking its wounds, but with the smell of victory in its nostrils.

Spirits would no doubt have been high when Percy arrived back at the lines, doubly so because the initial attack at Ypres, planned for 31 July, would not include any Australians. As Carlyon tells us, they had been scheduled for a long rest. The bravery and daring of the Australian soldiers had been known to the British commanders since the bloody battles of Fromelles and Pozières in the previous year and, increasingly, they had been used as shock troops since that time. The initial attack on Messines Ridge was another such example. As American correspondent Frederick Palmer wrote of Australia in 1917:

I want to see the land that breeds such men. They are free men if ever there were such; free whether they come from town or bush . . . Whenever I saw an Australian I thought: “Here is a very proud, individual man,” but also an Australian, particularly an Australian.

They were now to be given a richly deserved break from the conflict. However, rest or not, the troops were still close to the front line, and to action. As Lynch reflects, “Even the quietest parts of the line take their toll. Even in a quiet innings the wickets fall and players get their despatch to the pavilion, their innings ended”. On 23 June, its rest over, 3 Division took over the captured sector just north of St. Yves and west of the town of Warneton, which was still in German hands. There the troops established three lines of defence.

This work was done under pressure, however. Bean tells us that the German artillery, machine guns and snipers were kept busy in efforts to counteract the Australians’ industriousness. Nevertheless, despite all this hard work and a number of small actions, none of the Australian brigades was close enough to the German line to conduct an effective attack on it. Minor operations were undertaken in the area by units from 3 Division, with some success, but 39 Battalion’s general role at this time was to hold and further secure its section of the line. Percy would have experienced a lot of trench-digging and other construction work. His labouring background probably came in very handy!

The Battle of Passchendaele was a disaster for the British. The successful attack at Messines had warned the Germans that a major offensive at Ypres was imminent, and they reinforced their lines accordingly. And so tardy was the main attack after Messines that they had over a month in which to do it. With nearly a million men on each side, and with the Germans entrenched in their heavily fortified Hindenburg Line, Haig had neither a strategic nor a numerical advantage on the Ypres Front. When the first troops went over the tops of the trenches on 31 July, they would do so against the best advice of military and political planners. One of the biggest problems they would face would be mud, “gluey, intolerable mud”, as Leon Wolff describes it. The ground at Ypres is heavy clay. Water never drains away naturally. What is more, continual bombardments since 1914 had churned up the ground and destroyed the delicate drainage system that had been constructed by farmers many centuries before to make the area arable. When combined with rain, the new preliminary bombardment in 1917 would turn this ground into almost impassable mud. And rain it certainly did, causing British prime minister David Lloyd George to christen the conflict ‘the battle of the mud’.

As A. J. P. Taylor puts it:

Failure was obvious by the end of the first day to everyone except Haig and his immediate circle. The greatest advance was less than half a mile. The main German line was nowhere reached. Rain fell heavily. The ground, turned up by shellfire, turned to mud. Haig sent in tanks. These also vanished in the mud. Imperceptibly Haig changed his tone.

The only purpose of the battle [now] was to kill Germans and shake their morale.

Most war historians agree with Taylor. Captain Basil Liddell Hart describes the conflict as “the gloomiest drama in British military history . . . ‘Passchendaele’ has come to be . . . a synonym for military failure – a name black-bordered in the records of the British Army.” Even writing from a contemporary perspective, Bean called the plan ‘a huge gamble’. “They don’t realise,” he wrote about the British commanders, “how desperately hard it will be to fight down such opposition in the mud, rifles choked, L[ewis] G[uns] out of action, men tired and slow . . . Every step means dragging one foot out of the mud . . . I shall be very surprised if this fight succeeds.” At no stage in the war did Haig go anywhere near the front line, so he never had a real appreciation of the conditions in which the men were fighting. When his chief of staff visited the fighting zone - at Ypres – for the first time in November, he burst into tears and cried: “Good God, did we really send men to fight in that?” By then, however, his grief was all too late. “Passchendaele”, writes John Masters,

Sums up the Great War in itself, because Passchendaele is courage and sacrifice beyond understanding; Passchendaele is the ultimate in acceptance, in discipline; Passchendaele is mud, sleet, lice, mud, noise, jagged steel, horror piled on reeking horror, men and animals torn in pieces, mud seeded with brains and blood, mud heaving with putrifying thousands of fathers, sons and lovers; Passchendaele is appalling muddle, waste to terrify the soul. A German general described it as . . . the greatest martyrdom of the World War.

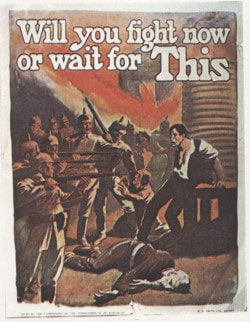

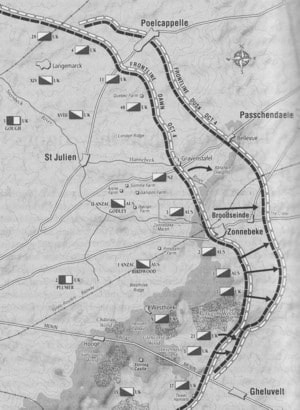

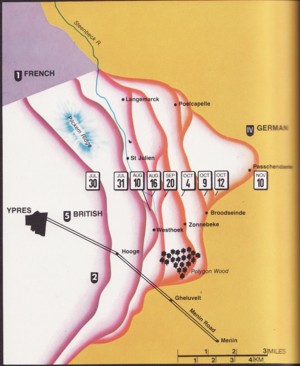

While the attacks at Ypres dragged on into August, Percy and his compatriots remained in the Messines area, being involved in minor skirmishes with their German counterparts and training for their inevitable involvement in the major conflict to the north. It would appear, however, that, at one stage for a short while, General Monash took his division to rest at Boulogne on the coast, where the men enjoyed sunshine and sports days. By 26 August, it had been decided that I Anzac Corps would soon relieve a British corps on the battlefield, and II Anzac Corps (to which Percy’s 3 Division belonged) would come in at a later stage, possibly to I Anzac’s left. I Anzac marched north to do this and entered the front line near Westhoek and Glencorse Wood on 16 September (see map p. 7 ). They went into attack on 20 September in heavy mud after overnight rain. Carlyon writes that many of them were wet from the waist down and carrying several pounds of mud on each boot (as well as their sixty-pound packs) as they assembled for the jump-off. Despite these handicaps, the troops gained a limited victory in what became known as the Battle of Menin Road. They advanced about 1 200 metres, but at the cost of 5 000 casualties. The total gain in territory as a result of this battle was about nine square kilometres. As Carlyon points out, it was hardly going to win the war. Haig, however, was delighted, and he was encouraged to move on and try to take Polygon Wood and Passchendaele Ridge. The attack at Polygon Wood, which began on 26 September and again featured I Anzac Corps, was also judged a success, with five and a half square kilometres of territory taken – but again at enormous human cost. There were 5 400 Australian casualties alone. As Carlyon puts it,

“In a week, in two short and ‘successful’ battles, the Australians had lost 10, 000 men to advance the allied line in Belgium a few thousand yards”.

After Polygon Wood, 4 and 5 Australian Divisions left the front line, and were replaced by 1, 2 and 3 Divisions, each of which moved north for the next step in the advance on Passchendaele. This would be the Battle of Broodseinde. According to Bean, this third step in the offensive was the most important. The objective was the section of the main ridge known as the ‘Broodseinde Ridge’. Since its abandonment by the British during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, this ridge had formed the main buttress of the German position in the area. From it, the Germans were able to look out on the British front in practically all directions. Capture this ridge, the allied planners believed, and their troops could sweep across it to Passchendaele. II Anzac Corps would be at the forefront, capturing the most strategic part of the ridge and then playing the chief part by extending the capture of the ridge to beyond Passchendaele. 3 Division, as can be seen from the map below, would lead the attack towards Broodseinde village.

The 3rd Australian Division can be seen just behind the line, directly west of the town of Broodseinde. Bean tells us that the date for the first attack was set for 4 October, almost as soon as II Anzac Corps could reach the battlefield from its rest areas in the south. There was some haste involved as autumn was advancing, and the chances of the weather deteriorating were increasing every day. 3 Division reached the front on 29 September, and found the roads, tracks and telegraph lines in poor condition – something the men were not able to do much about before the planned attack five days later.

The chief danger at Broodseinde, according to Bean, was the chance of a break in the weather. Up until 2 October, Percy and 3 Division had been plagued by dust clouds as they moved into position. With exquisite timing, however, the rain started setting in for winter on the third, just before the initial attack was to go ahead. Masters writes that it was a steady, cold rain with icy winds. He continues: By this time the battlefield had absorbed about eighty million shells (twenty million more were to come). Both army commanders . . . pressed to end the campaign; but Haig noticed that the enemy were in possession of the Passchendaele ridge.Let them just be cleared off that, and then there would be no better winter quarters – high ground, no mud, a good lateral road behind the front. No one seems to have pointed out that the assaults on the ridge would certainly create mud where none had been before.

For the men of 3 Division, the attack took place on a very narrow front near Zonnebeke at 6.00 am. Many of them found that they had to cross a veritable bog, as most of the existent tracks in the area had been destroyed by the preliminary bombardment. They moved on, however, against fierce German resistance and bombardment, and achieved their initial objective. The attack was, says Bean, “an overwhelming success”. To put this success into perspective, however, we need to remember that the Australian forces had advanced less than two kilometres, and had lost 6 432 men in the process. 39 Battalion alone lost eight officers and 202 men. As Masters puts it, Broodseinde was a success to the extent of another mile deep, seven miles wide, “but no one cared any more”. The troops of 3 Division dug in quickly at their objective (“perhaps the most complete and accurately-sited front and support lines ever made by Australians in battle,” writes Bean) and successfully fought of German counter attacks. Regardless of the limited nature of their success, their skill and bravery cannot be understated. As one would expect with an official history, Bean puts a positive perspective on the Battle of Broodseinde in writing: among many well-informed observers at the front, there was a definite feeling that this battle was the most complete success so far won by the British Army in France. For the first time in years, at noon on October 4th on the heights in Ypres, British troops on the Western Front stood face to face with the possibility of decisive success.

Haig was chuffed by the success at Broodseinde. It cemented his incorrect belief that the Germans were on the point of collapse. Even Monash was caught up in the euphoria, writing to his wife that “great happenings are possible in the very near future”.Both men encouraged a quick advance to the ultimate target: the capture of Passchendaele. It was to be achieved in two steps: a short preparatory advance scheduled for 10 October, and then a much deeper advance on the thirteenth, finishing with the fall of the town. 3 Division would be at the centre of both attacks. As ‘Robbie’ Burns reminds us, however, the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry, and the rain that began as a drizzle on 3 October really set in after noon on the fourth. At 4.00 pm on 8 October, it became a torrent. The meteorological experts saw no improvement in sight. Yet Haig decided to go on with the attacks, bringing each one forward by a day, rather than abandoning his strategic designs for 1917. As Carlyon puts it, if he took Passchendaele, he could at least say that he had thrown the Germans off the ridges. This was despite the fact that the almost impassable mud made the movement and proper location of supporting artillery, and the maintenance of the infantry’s freshness, almost impossible. Against their better judgement, his commanders turned deaf ears and blind eyes. Passchendaele, comments Taylor, was the blindest slaughter of a blind war.

The first attack, at 5.20 am on 9 October, was an unmitigated disaster. New reinforcements even had difficulty in getting to the front in time to go over the top, so bad were the conditions. And when they did, they were exhausted before they started. This ‘Battle of Poelcappelle’, as it was later called, achieved no appreciable gain (the front line hardly moved), and 1 253 Australian casualties. Despite this, and the continuing rain, Haig was determined to push on with the attack on 12 October which, he hoped, would result in the fall of Passchendaele. This assault would feature the men of 3 Division. Because of Haig’s misreading of the results at Poelcappelle, the men were given an almost Herculean task: cover at least two kilometres in one day, at a pace greater than ever achieved over dry land since the beginning of trench warfare in 1914 – and without adequate artillery cover as many of the batteries (along with their shells) were bogged down and unable to reach their intended positions by the set time.

Percy’s brigade – the tenth – was one of two selected to lead the attack towards Passchendaele ridge and village. Bean tells us that, on the night of 10th October, the men were on the flats east of Ypres. They had no tents and were "bivouacked in the wet grass, under such timber or old sheets of iron as they could find". As they approached the front the next evening, already tired and wet, they were constantly bombarded by the Germans, not only with high explosive, but also with gas. It is possible that some of this gas was the new mustard type (later given the significant name of ‘Yperite’ in recognition of the location of its first usage) that burned on contact with exposed parts of the body, or if inhaled. They finally got into position by 3.20 am, and it started raining heavily at 3.30. All the men could do was pull their waterproof sheets over their heads and try to sleep. Fortunately, the rain stopped at 4.20, and the attack started an hour later, preceded by a hopelessly inadequate bombardment of the ridge.

“In a week, in two short and ‘successful’ battles, the Australians had lost 10, 000 men to advance the allied line in Belgium a few thousand yards”.

After Polygon Wood, 4 and 5 Australian Divisions left the front line, and were replaced by 1, 2 and 3 Divisions, each of which moved north for the next step in the advance on Passchendaele. This would be the Battle of Broodseinde. According to Bean, this third step in the offensive was the most important. The objective was the section of the main ridge known as the ‘Broodseinde Ridge’. Since its abandonment by the British during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915, this ridge had formed the main buttress of the German position in the area. From it, the Germans were able to look out on the British front in practically all directions. Capture this ridge, the allied planners believed, and their troops could sweep across it to Passchendaele. II Anzac Corps would be at the forefront, capturing the most strategic part of the ridge and then playing the chief part by extending the capture of the ridge to beyond Passchendaele. 3 Division, as can be seen from the map below, would lead the attack towards Broodseinde village.

The 3rd Australian Division can be seen just behind the line, directly west of the town of Broodseinde. Bean tells us that the date for the first attack was set for 4 October, almost as soon as II Anzac Corps could reach the battlefield from its rest areas in the south. There was some haste involved as autumn was advancing, and the chances of the weather deteriorating were increasing every day. 3 Division reached the front on 29 September, and found the roads, tracks and telegraph lines in poor condition – something the men were not able to do much about before the planned attack five days later.

The chief danger at Broodseinde, according to Bean, was the chance of a break in the weather. Up until 2 October, Percy and 3 Division had been plagued by dust clouds as they moved into position. With exquisite timing, however, the rain started setting in for winter on the third, just before the initial attack was to go ahead. Masters writes that it was a steady, cold rain with icy winds. He continues: By this time the battlefield had absorbed about eighty million shells (twenty million more were to come). Both army commanders . . . pressed to end the campaign; but Haig noticed that the enemy were in possession of the Passchendaele ridge.Let them just be cleared off that, and then there would be no better winter quarters – high ground, no mud, a good lateral road behind the front. No one seems to have pointed out that the assaults on the ridge would certainly create mud where none had been before.

For the men of 3 Division, the attack took place on a very narrow front near Zonnebeke at 6.00 am. Many of them found that they had to cross a veritable bog, as most of the existent tracks in the area had been destroyed by the preliminary bombardment. They moved on, however, against fierce German resistance and bombardment, and achieved their initial objective. The attack was, says Bean, “an overwhelming success”. To put this success into perspective, however, we need to remember that the Australian forces had advanced less than two kilometres, and had lost 6 432 men in the process. 39 Battalion alone lost eight officers and 202 men. As Masters puts it, Broodseinde was a success to the extent of another mile deep, seven miles wide, “but no one cared any more”. The troops of 3 Division dug in quickly at their objective (“perhaps the most complete and accurately-sited front and support lines ever made by Australians in battle,” writes Bean) and successfully fought of German counter attacks. Regardless of the limited nature of their success, their skill and bravery cannot be understated. As one would expect with an official history, Bean puts a positive perspective on the Battle of Broodseinde in writing: among many well-informed observers at the front, there was a definite feeling that this battle was the most complete success so far won by the British Army in France. For the first time in years, at noon on October 4th on the heights in Ypres, British troops on the Western Front stood face to face with the possibility of decisive success.

Haig was chuffed by the success at Broodseinde. It cemented his incorrect belief that the Germans were on the point of collapse. Even Monash was caught up in the euphoria, writing to his wife that “great happenings are possible in the very near future”.Both men encouraged a quick advance to the ultimate target: the capture of Passchendaele. It was to be achieved in two steps: a short preparatory advance scheduled for 10 October, and then a much deeper advance on the thirteenth, finishing with the fall of the town. 3 Division would be at the centre of both attacks. As ‘Robbie’ Burns reminds us, however, the best-laid plans of mice and men often go awry, and the rain that began as a drizzle on 3 October really set in after noon on the fourth. At 4.00 pm on 8 October, it became a torrent. The meteorological experts saw no improvement in sight. Yet Haig decided to go on with the attacks, bringing each one forward by a day, rather than abandoning his strategic designs for 1917. As Carlyon puts it, if he took Passchendaele, he could at least say that he had thrown the Germans off the ridges. This was despite the fact that the almost impassable mud made the movement and proper location of supporting artillery, and the maintenance of the infantry’s freshness, almost impossible. Against their better judgement, his commanders turned deaf ears and blind eyes. Passchendaele, comments Taylor, was the blindest slaughter of a blind war.

The first attack, at 5.20 am on 9 October, was an unmitigated disaster. New reinforcements even had difficulty in getting to the front in time to go over the top, so bad were the conditions. And when they did, they were exhausted before they started. This ‘Battle of Poelcappelle’, as it was later called, achieved no appreciable gain (the front line hardly moved), and 1 253 Australian casualties. Despite this, and the continuing rain, Haig was determined to push on with the attack on 12 October which, he hoped, would result in the fall of Passchendaele. This assault would feature the men of 3 Division. Because of Haig’s misreading of the results at Poelcappelle, the men were given an almost Herculean task: cover at least two kilometres in one day, at a pace greater than ever achieved over dry land since the beginning of trench warfare in 1914 – and without adequate artillery cover as many of the batteries (along with their shells) were bogged down and unable to reach their intended positions by the set time.

Percy’s brigade – the tenth – was one of two selected to lead the attack towards Passchendaele ridge and village. Bean tells us that, on the night of 10th October, the men were on the flats east of Ypres. They had no tents and were "bivouacked in the wet grass, under such timber or old sheets of iron as they could find". As they approached the front the next evening, already tired and wet, they were constantly bombarded by the Germans, not only with high explosive, but also with gas. It is possible that some of this gas was the new mustard type (later given the significant name of ‘Yperite’ in recognition of the location of its first usage) that burned on contact with exposed parts of the body, or if inhaled. They finally got into position by 3.20 am, and it started raining heavily at 3.30. All the men could do was pull their waterproof sheets over their heads and try to sleep. Fortunately, the rain stopped at 4.20, and the attack started an hour later, preceded by a hopelessly inadequate bombardment of the ridge.

Bean reports that, despite the depressing conditions, 3 Division was eager to achieve the distinction of capturing Passchendaele and even took an Australian flag along to plant in the centre of the town. However, there was confusion from the moment the troops went over the tops of the trenches, created by the almost impassable mud and inadequate or damaged communication lines. In addition, of course, the Germans were providing fierce opposition, forcing the Australians to advance by hopping from one water-filled shell hole to another. Casualties were high. Nevertheless, one small party pushed on for Passchendaele village, captured a pillbox, and reached the church. When they saw no other troops coming up to join them, however, they withdrew back to their line.

The men of 10 Brigade had reached their first objective, but they were under heavy fire and in danger of being outflanked by the Germans. Monash ordered 39 Battalion, supposedly in reserve, forward to reinforce the front line. In reality, however, 39 Battalion had already been involved in the fighting to a large extent, and had suffered a considerable number of casualties (180 in total for the day). There were no reinforcements. At 3.00 pm the rain started again, and the Germans continued to infiltrate, so the officers of 10 Brigade decided to withdraw. The withdrawal was completed by 3.30, and 3 Division was almost back to its starting point. Many men were left behind in the morass. 3 Division suffered 3 200 casualties (out of a total of almost 11 000), hundreds of them losing their lives by drowning in the mud and water-filled shell holes while going up to the line, or becoming stuck fast and being picked off by German snipers. Moreover, many mules and horses drowned, especially those carrying heavy shells, and, in Masters’ words, guns vanished by the battery, swallowed up in the heaving ocean of mud. Bean comments that “. . . while the attacking troops had been exhausted and depressed, the Germans, in spite of the severity of the casualties on their side also, had been encouraged and reinvigorated.” German commander Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria commented in his diary that the rain was their “most effective ally”.

The attack on 12 October negated much of the success at Polygon Wood and Broodseinde. Nevertheless, Haig decided to continue on, planning to use Canadian forces in another assault on 26 October. II Anzac Corps stayed in line until 22 October, constantly bombarded with shell and mustard gas. Bean points out that The Germans used this new agent with dreadful success, masking the shoots with a bombardment of high explosive and throwing in first “sneezing gas” . . . which rendered it difficult to keep the respirators on, and then changing over to mustard gas . . . Masks would have to be worn during the whole bombardment, precluding sleep. Bivouacs [field camps] were frequently knocked in and their ground, saturated with mustard oil, could not be reoccupied.

During this time, the Germans vacated some of the territory initially captured on 12 October, and 3 Division reoccupied it. On 22 October, along with the rest of II Anzac Corps, 3 Division was taken out of the line for a short rest and replaced by Canadian troops. Their attack on 26 October was almost a carbon copy of the Australians’ one on the twelfth, with identical results. The weather was deteriorating now: continuing rain, but accompanied by very low temperatures and high winds. In the three subsequent attacks - on 30 October and 6 and 10 November - the Canadians finally captured Passchendaele and some territory beyond it. However, the strategic situation in Belgium changed little as a result. Something less than eight kilometres of territory had been gained, mainly, As Bryan Cooper comments, “a few miles of cratered mud-flat and the ruins of a village that was called Passchendaele”. The Hindenburg Line remained unbroken and unflanked. The estimated cost of this ‘success’ was 70 000 allied dead and 205 000 casualties. Liddell Hart sums up this futile conflict:. . . when, on November 4th, a sudden advance . . . gained the empty satisfaction of occupying the site of Passchendaele village, the official curtain was at last run down on the pitiful tragedy of ‘Third Ypres’. It was the long overdue close of a campaign which had brought the British armies to the verge of exhaustion, one in which had been enacted the most dolorous scenes in British military history, and for which the only justification evoked the reply that, in order to absorb the enemy’s attention and forces, Haig chose the spot most difficult for himself and least vital to his enemy. Intending to absorb the enemy’s reserves, his own were absorbed.

Cochrane provides the Australian perspective in writing:

1917 was the worst year of the war for Australian casualties: 55,000 in all, 38,000 at Passchendaele alone. The futility of this final fling in the Ypres campaign was reflected in horrific statistics – 35 Australian killed for every metre of ground seized. Among the survivors the most potent memories were of men drowning in mud, unreachable, their cries followed by the most awful silence; the living were racked with guilt and sadness.

The immediate reason for the ending of the battle at Passchendaele was the collapse of the allied Italian army against the Germans and Austrians at the Battle of Caporetto, and the resultant need to send more forces to that battlefront to bolster the devastated Italians. Percy and all the surviving men in Flanders must have breathed an intense sigh of relief that their offensive had finally been called off. Third Ypres had, in Bean’s words, made a clean sweep of more than half the Australian infantry, 38 000 casualties being suffered. 3 Division suffered particularly badly, to the point where its integrity as a fighting unit was under threat. It was short of about 1 500 men. With recruitment numbers in Australia being so low, it (as well as its fellow divisions) would have to be reinforced mainly by its returning sick and wounded. In late October, the overall Australian commander General Birdwood, encouraged by prime minister ‘Billy’ Hughes, suggested combining 1, 2, 3 and 5 Divisions into one Australian Corps under Monash, with 4 Division being located at Boulogne as a depot division for the others. The new corps would be rested on the now quiet Messines Front for the winter, preparing to be involved on offensives planned for the Spring of 1918. Haig willingly accepted this plan, and Bean tell us that everyone was delighted with the idea. The men of the 3rd Division, in particular, were “overjoyed”. Now they could be brigaded with the main body of Australian infantry, instead of being seen as something ‘different’ because of their origins. Bean reports that “ the brims of the felt hats, which, to create esprit de corps by a distinction from other divisions, General Monash had caused to be worn unlooped, were turned up the same day”.

So, on 13 November, 3 and 5 Divisions of the new Australian Corps began to take over the southern and northern sectors of the Messines Front. For Percy and the rest of 39 Battalion, this meant returning to the area between Ploegsteert Wood and St. Yves. By this time, the weather was freezing, and Birdwood was keen to see that the men were as comfortable as possible. In particular, he wanted to avoid large-scale outbreaks of “trench foot” (caused by immersion in constantly wet ground) and chest infections. He arranged for the regular drying and changing of socks in the trenches, and encouraged football and other sport competitions, as well as cinema shows, concerts and canteens for the men in the rear. Bean reports that, for the next two months, battalion football competitions were the extreme interest behind the Messines Front. The men wore jumpers in battalion colours and played on specially marked grounds.

However, every man also had to do his rotation in the front line nearby. The end of the battle at Passchendaele did not lead to any cessation in hostilities along the front. The intensity of the conflict had declined as both sides licked their wounds, but the occasional high explosive or gas shell, grenade, machine gunning, sniping and night time raid (usually done to seek information about the enemy dispositions) continued unabated. The trenches remained a maelstrom of rain, mud, barbed wire, and dismembered and half-buried corpses, interred and then exposed again by constant shellfire. It was while he was undertaking such a rotation that Percy was involved in a night time raid on the opposing German trenches on 30 November. Eighty-two men and four officers sneaked across no man’s land, through the wire, and entered the enemy stronghold. As the citation for Percy’s award puts it:

"Near WARNETON, during a raid on the enemy, on the night 30th November/1st December 1917, this man displayed conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty. He did very fine work in company with Private DONOHUE in searching and bombing enemy dugouts during raid and was instrumental in securing a live prisoner".

For this brave action, Percy was awarded the Military Medal on 4 December. He must have been very proud of his achievement. A captured enemy soldier was a real prize, as he could be interrogated by the intelligence officers and might provide valuable information about troop movements and the location of various units.