OOSTENDE NEW COMMUNAL CEMETERY

West-Vlaanderen

Belgium

GPS Coordinates: Latitude: 51.20988 Longitude: 2.91582

Location Information

Oostende New Communal Cemetery is located in the town of Oostende on the Stuiverstraat, a road leading from the R31 Elisabethlaan.

Travelling towards Brussels on the R31 the Stuiverstraat is located 500 metres after the junction with the N33.

The cemetery is located 800 metres along the Stuiverstraat on the right hand side of the road.

Visiting Information

This cemetery is open from 07.30 hrs to 12.00 hrs and from 13.00 hrs to 16.30 hrs.

Wheelchair access to site possible, but may be by alternative entrance.

Historical Information

From the 13th to the 22nd August, 1914 Oostende (also known as Ostende) was a British seaplane base, and for four days at the end of the month it was protected by the British Marine Brigade. From the 7th to the 12th October it was the seat of the Belgian Government. On the 8th October the 3rd Cavalry Division landed at Oostende; but the port was closed on the 14th and entered by the Germans next day.

Thereafter, Oostende was periodically bombarded by ships of the Royal Navy and bombed by Allied airmen. On 23 April and 10 May 1918, it was raided by the Dover patrol in an attempt to block the port as an outlet for German torpedo boats and submarines based at Bruges. The attack of 23 April failed to block the harbour but that of 10 May, when "Vindictive" was sunk in the channel, partially succeeded. The town was finally entered by Allied forces on 17 October 1918, without opposition.

During the Second World War, the British Expeditionary Force was involved in the later stages of the defence of Belgium following the German invasion in May 1940, and suffered many casualties in covering the withdrawal to Dunkirk. Commonwealth forces did not return until September 1944 (Oostende was liberated by the Canadians on 8 September), but in the intervening years, many airmen were shot down or crashed in raids on strategic objectives in Belgium, or while returning from missions over Germany.

The Commonwealth plots at Oostende New Communal Cemetery contain 50 burials of the First World War and 366 from the Second World War, 75 of the latter unidentified. The plots also contain eight non-war burials and eight war graves of other nationalities.

Total Burials: 432.

World War One Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 43, Canada 1. Total 44.

World War Two Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 277, Canada 8, Australia 3, Poland 3, New Zealand 3, Netherlands 1. Total 295.

Images in this gallery © Werner Van Caneghem

Hotels, etc. on the Digue, Ostend, with the old lighthouse on the left. Taken from the end of the Western Jetty. October 1918.

© IWM (Q 19921)

© IWM (Q 19921)

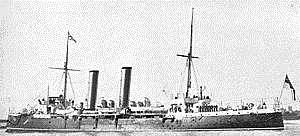

HMS Vindictive

HMS Vindictive

HMS Vindictive was a British protected cruiser of the Arrogant class built at Chatham Dockyard. She was launched on 9 December 1897 and completed in 1899. Serving with the Mediterranean Squadron in 1901.

After a refit in 1909-10 for service with the 3rd Division of the Home Fleet. She later became a tender to the training establishment HMS Vernon in March 1912. Although obsolescent by the outbreak of World War I, in August 1914 she was assigned to the 9th Cruiser Squadron and captured the German merchantmen Schlesien and Slawentzitz on 7 August and 8 September respectively. By 1915 she was stationed on the southeast coast of South America and from 1916 to late 1917 she served in the White Sea.

Early in 1918 she was fitted out for the Zeebrugge Raid. Most of her guns were replaced by howitzers, flame-throwers and mortars. On 23 April 1918 she was in fierce action at Zeebrugge when she went alongside the Mole, and her upperworks were badly damaged by gunfire, her Captain, Alfred Carpenter was awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions during the raid. This event was famously painted by Charles de Lacy, the painting hangs in the Britannia Royal Naval College.

She was sunk as a blockship at Ostend during the Second Ostend Raid on 10 May 1918. The wreck was raised on 16 August 1920 and subsequently broken up. The bow section has been preserved in Ostend harbour serving as a memorial. One of Vindictive's 7.5-inch howitzers was acquired and preserved by the Imperial War Museum.

The name "Vindictive" lives on as the aircraft carrier HMS "Cavendish" was later re-named "Vindictive".

After a refit in 1909-10 for service with the 3rd Division of the Home Fleet. She later became a tender to the training establishment HMS Vernon in March 1912. Although obsolescent by the outbreak of World War I, in August 1914 she was assigned to the 9th Cruiser Squadron and captured the German merchantmen Schlesien and Slawentzitz on 7 August and 8 September respectively. By 1915 she was stationed on the southeast coast of South America and from 1916 to late 1917 she served in the White Sea.

Early in 1918 she was fitted out for the Zeebrugge Raid. Most of her guns were replaced by howitzers, flame-throwers and mortars. On 23 April 1918 she was in fierce action at Zeebrugge when she went alongside the Mole, and her upperworks were badly damaged by gunfire, her Captain, Alfred Carpenter was awarded a Victoria Cross for his actions during the raid. This event was famously painted by Charles de Lacy, the painting hangs in the Britannia Royal Naval College.

She was sunk as a blockship at Ostend during the Second Ostend Raid on 10 May 1918. The wreck was raised on 16 August 1920 and subsequently broken up. The bow section has been preserved in Ostend harbour serving as a memorial. One of Vindictive's 7.5-inch howitzers was acquired and preserved by the Imperial War Museum.

The name "Vindictive" lives on as the aircraft carrier HMS "Cavendish" was later re-named "Vindictive".

The remains of HMS VINDICTIVE in the entrance to Ostend harbour where she was sunk as a blockship. (1918)

© IWM (Q 23117)

© IWM (Q 23117)

The seven graves of VINDICTIVE heroes at Ostend. According to the Burgomaster the Germans gave the VINDICTIVE dead an impressive funeral.

© IWM (Q 19252)

© IWM (Q 19252)

H. M. S. Vindictive Memorial

Ostend, Belgium

(Pictures in gallery below © Werner Van Caneghem)

Images in this gallery Johan Pauwels

Bombs burst across buildings and on the quays during an attack by six Bristol Blenheims of No. 88 Squadron RAF at Slykens, east of Ostend on the Ostend-Bruges Canal.

© IWM (HU 93069

Bombs burst across buildings and on the quays during an attack by six Bristol Blenheims of No. 88 Squadron RAF at Slykens, east of Ostend on the Ostend-Bruges Canal.

© IWM (HU 93069

The First Ostend Raid - 1918

The First Ostend Raid (part of Operation ZO) was the first of two attacks by the Royal Navy on the German-held port of Ostend during the late spring of 1918 during the First World War. Ostend was attacked in conjunction with the neighbouring harbour of Zeebrugge on 23 April in order to block the vital strategic port of Bruges, situated 6 miles inland and ideally situated to conduct raiding operations on the British coastline and shipping lanes. Bruges and its satellite ports were a vital part of the German plans in their war on Allied commerce (Handelskrieg) because Bruges was close to the troopship lanes across the English Channel and allowed much quicker access to the Western Approaches for the U-boat fleet than their bases in Germany.

The plan of attack was for the British raiding force to sink two obsolete cruisers in the canal mouth at Ostend and three at Zeebrugge, thus preventing raiding ships leaving Bruges. The Ostend canal was the smaller and narrower of the two channels giving access to Bruges and so was considered a secondary target behind the Zeebrugge Raid. Consequently, fewer resources were provided to the force assaulting Ostend. While the attack at Zeebrugge garnered some limited success, the assault on Ostend was a complete failure. The German marines who defended the port had taken careful preparations and drove the British assault ships astray, forcing the abortion of the operation at the final stage.

Three weeks after the failure of the operation, a second attack was launched which proved more successful in sinking a blockship at the entrance to the canal but ultimately did not close off Bruges completely. Further plans to attack Ostend came to nothing during the summer of 1918, and the threat from Bruges would not be finally stopped until the last days of the war, when the town was liberated by Allied land forces.

Bruges

Bruges had been captured by the advancing German divisions during the Race for the Sea and had been rapidly identified as an important strategic asset by the German Navy. Bruges was situated 6 miles inland at the centre of a network of canals which emptied into the sea at the small coastal towns of Zeebrugge and Ostend. This land barrier protected Bruges from bombardment by land or sea by all but the very largest calibre artillery and also secured it against raiding parties from the Royal Navy. Capitalising on the natural advantages of the port, the German Navy constructed extensive training and repair facilities at Bruges, equipped to provide support for several flotillas of destroyers, torpedo boats and U-boats.

By 1916, these raiding forces were causing serious concern in the Admiralty as the proximity of Bruges to the British coast, to the troopship lanes across the English Channel and for the U-boats, to the Western Approaches; the heaviest shipping lanes in the World at the time. In the late spring of 1915, Admiral Reginald Bacon had attempted without success to destroy the lock gates at Ostend with monitors. This effort failed, and Bruges became increasingly important in the Atlantic Campaign, which reached its height in 1917. By early 1918, the Admiralty was seeking ever more radical solutions to the problems raised by unrestricted submarine warfare, including instructing the "Allied Naval and Marine Forces" department to plan attacks on U-boat bases in Belgium.

The "Allied Naval and Marine Forces" was a newly formed department created with the purpose of conducting raids and operations along the coastline of German-held territory. The organisation was able to command extensive resources from both the Royal and French navies and was commanded by Admiral Roger Keyes and his deputy, Commodore Hubert Lynes. Keyes, Lynes and their staff began planning methods of neutralising Bruges in late 1917 and by April 1918 were ready to put their plans into operation.

The Plan

To block Bruges, Keyes and Lynes decided to conduct two raids on the ports through which Bruges had access to the sea. Zeebrugge was to be attacked by a large force consisting of three blockships and numerous supporting warships. Ostend was faced by a similar but smaller force under immediate command of Lynes. The plan was for two obsolete cruisers—HMS Sirius and Brilliant—to be expended in blocking the canal which emptied at Ostend. These ships would be stripped to essential fittings and their lower holds and ballast filled with rubble and concrete. This would make them ideal barriers to access if sunk in the correct channel at the correct angle.

When the weather was right, the force would cross the English Channel in darkness and attack shortly after midnight to coincide with the Zeebrugge Raid a few miles up the coast. By coordinating their operations, the assault forces would stretch the German defenders and hopefully gain the element of surprise. Covering the Inshore Squadron would be heavy bombardment from an offshore squadron of monitors and destroyers as well as artillery support from Royal Marine artillery near Ypres in Allied-held Flanders. Closer support would be offered by several flotillas of motor launches, small torpedo boats and Coastal Motor Boats which would lay smoke screens to obscure the advancing blockships as well as evacuate the crews of the cruisers after they had blocked the channel.

The First Ostend Raid - 1918

The First Ostend Raid (part of Operation ZO) was the first of two attacks by the Royal Navy on the German-held port of Ostend during the late spring of 1918 during the First World War. Ostend was attacked in conjunction with the neighbouring harbour of Zeebrugge on 23 April in order to block the vital strategic port of Bruges, situated 6 miles inland and ideally situated to conduct raiding operations on the British coastline and shipping lanes. Bruges and its satellite ports were a vital part of the German plans in their war on Allied commerce (Handelskrieg) because Bruges was close to the troopship lanes across the English Channel and allowed much quicker access to the Western Approaches for the U-boat fleet than their bases in Germany.

The plan of attack was for the British raiding force to sink two obsolete cruisers in the canal mouth at Ostend and three at Zeebrugge, thus preventing raiding ships leaving Bruges. The Ostend canal was the smaller and narrower of the two channels giving access to Bruges and so was considered a secondary target behind the Zeebrugge Raid. Consequently, fewer resources were provided to the force assaulting Ostend. While the attack at Zeebrugge garnered some limited success, the assault on Ostend was a complete failure. The German marines who defended the port had taken careful preparations and drove the British assault ships astray, forcing the abortion of the operation at the final stage.

Three weeks after the failure of the operation, a second attack was launched which proved more successful in sinking a blockship at the entrance to the canal but ultimately did not close off Bruges completely. Further plans to attack Ostend came to nothing during the summer of 1918, and the threat from Bruges would not be finally stopped until the last days of the war, when the town was liberated by Allied land forces.

Bruges

Bruges had been captured by the advancing German divisions during the Race for the Sea and had been rapidly identified as an important strategic asset by the German Navy. Bruges was situated 6 miles inland at the centre of a network of canals which emptied into the sea at the small coastal towns of Zeebrugge and Ostend. This land barrier protected Bruges from bombardment by land or sea by all but the very largest calibre artillery and also secured it against raiding parties from the Royal Navy. Capitalising on the natural advantages of the port, the German Navy constructed extensive training and repair facilities at Bruges, equipped to provide support for several flotillas of destroyers, torpedo boats and U-boats.

By 1916, these raiding forces were causing serious concern in the Admiralty as the proximity of Bruges to the British coast, to the troopship lanes across the English Channel and for the U-boats, to the Western Approaches; the heaviest shipping lanes in the World at the time. In the late spring of 1915, Admiral Reginald Bacon had attempted without success to destroy the lock gates at Ostend with monitors. This effort failed, and Bruges became increasingly important in the Atlantic Campaign, which reached its height in 1917. By early 1918, the Admiralty was seeking ever more radical solutions to the problems raised by unrestricted submarine warfare, including instructing the "Allied Naval and Marine Forces" department to plan attacks on U-boat bases in Belgium.

The "Allied Naval and Marine Forces" was a newly formed department created with the purpose of conducting raids and operations along the coastline of German-held territory. The organisation was able to command extensive resources from both the Royal and French navies and was commanded by Admiral Roger Keyes and his deputy, Commodore Hubert Lynes. Keyes, Lynes and their staff began planning methods of neutralising Bruges in late 1917 and by April 1918 were ready to put their plans into operation.

The Plan

To block Bruges, Keyes and Lynes decided to conduct two raids on the ports through which Bruges had access to the sea. Zeebrugge was to be attacked by a large force consisting of three blockships and numerous supporting warships. Ostend was faced by a similar but smaller force under immediate command of Lynes. The plan was for two obsolete cruisers—HMS Sirius and Brilliant—to be expended in blocking the canal which emptied at Ostend. These ships would be stripped to essential fittings and their lower holds and ballast filled with rubble and concrete. This would make them ideal barriers to access if sunk in the correct channel at the correct angle.

When the weather was right, the force would cross the English Channel in darkness and attack shortly after midnight to coincide with the Zeebrugge Raid a few miles up the coast. By coordinating their operations, the assault forces would stretch the German defenders and hopefully gain the element of surprise. Covering the Inshore Squadron would be heavy bombardment from an offshore squadron of monitors and destroyers as well as artillery support from Royal Marine artillery near Ypres in Allied-held Flanders. Closer support would be offered by several flotillas of motor launches, small torpedo boats and Coastal Motor Boats which would lay smoke screens to obscure the advancing blockships as well as evacuate the crews of the cruisers after they had blocked the channel.

The Attack

The assaults on Zeebrugge and Ostend were eventually launched on 23 April, after twice being delayed by poor weather. The Ostend force arrived off the port shortly before midnight and made final preparations; the monitors took up position offshore and the small craft moved forward to begin laying smoke. Covering the approach, the monitors opened fire on German shore defences, including the powerful "Tirpitz" battery, which carried 11 inch guns. As a long range artillery duel developed, the cruisers began their advance towards the harbour mouth, searching for the marker buoys which indicated the correct passage through the diverse sandbanks which made navigation difficult along the Belgian coast.

It was at this stage that the attack began to go seriously wrong. Strong winds blowing off the land swept the smoke screen into the face of the advancing cruisers, blinding their commanders who attempted to navigate by dead reckoning. The same wind disclosed the Inshore Squadron to the German defenders who immediately opened up a withering fire on the blockships. With their volunteer crews suffering heavy casualties, the commanders increased speed despite the poor visibility and continued groping through the narrow channels inshore, searching for the Stroom Bank buoy which directed shipping into the canal.

Commander Alfred Godsal led the assault in HMS Brilliant and it was he who stumbled into the most effective German counter-measure first. As Brilliant staggered through the murk, the lookout spotted the buoy ahead and Godsal headed directly for it, coming under even heavier fire as he did so. Passing the navigation marker at speed, the cruiser was suddenly brought to a halt with a juddering lurch, throwing men to the decks and sticking fast in deep mud well outside the harbour mouth. Before warnings could be relayed to the Sirius following up close behind, she too passed the buoy and her captain Lieutenant-Commander Henry Hardy was shocked to see Brilliant dead ahead. With no time to manoeuvre, Sirius ploughed into the port quarter of Brilliant, the blockships settling into the mud in a tangle of wreckage.

Artillery and long-range machine gun fire continued to riddle the wrecks and the combined crews were ordered to evacuate as the officers set the scuttling charges which would sink the blockships in their current, useless locations. As men scrambled down the side of the cruisers into Coastal Motor Boats which would relay them to the Offshore Squadron, destroyers moved closer to Ostend to cover the retreat and the monitors continued their heavy fire. Godsal was the last to leave, picked up by launch ML276 commanded by Lieutenant Rowley Bourke. With the main assault a complete failure, the blockading forces returned to Dover and Dunkirk to assess the disaster.

"Their Lordships will share our disappointment at the defeat of our plans by the legitimate ruse of the enemy."

Admiral Keyes' report to the Admiralty.

When the forces had reassembled and the commanders conferred, the full facts of the failed operation were revealed. The German commander of Ostend had been better prepared than his counterpart at Zeebrugge and had recognised that without the navigation buoy no night attack on Ostend could be successful without a strong familiarity with the port, which none of the British navigators possessed. However, rather than simply remove the buoy, the German commander had ordered it moved 2,400 yards east of the canal mouth into the centre of a wide expanse of sandbanks, acting as a fatal decoy for any assault force.

The Aftermath

The assault at Zeebrugge a few miles away from Ostend was more successful and the blocking of the major channel did cause some consternation amongst the German forces in Bruges. The larger raiders could no longer leave the port, but smaller ships, including most submarines, were still able to traverse via Ostend. In addition, within hours a narrow channel had also been carved through Zeebrugge too, although British intelligence did not realise this for several weeks. The defeat at Ostend did not entirely dampen the exuberant British media and public reaction to Zeebrugge, but in the Admiralty and particularly in the Allied Naval and Marine Forces the failure to completely neutralise Bruges rankled.

A second operation was planned for 10 May using the cruiser HMS Vindictive and proved more successful, but ultimately it also failed to completely close off Bruges. A third planned operation was never conducted as it rapidly became clear that the new channel carved at Zeebrugge was enough to allow access for U-boats, thus calling for an even larger double assault, which would stretch the resources of the "Allied Naval and Marine Forces" too far. British losses in the three futile attempts to close Bruges cost over 600 casualties and the loss of several ships but Bruges would remain an active raiding base for the German Navy until October 1918.

The assaults on Zeebrugge and Ostend were eventually launched on 23 April, after twice being delayed by poor weather. The Ostend force arrived off the port shortly before midnight and made final preparations; the monitors took up position offshore and the small craft moved forward to begin laying smoke. Covering the approach, the monitors opened fire on German shore defences, including the powerful "Tirpitz" battery, which carried 11 inch guns. As a long range artillery duel developed, the cruisers began their advance towards the harbour mouth, searching for the marker buoys which indicated the correct passage through the diverse sandbanks which made navigation difficult along the Belgian coast.

It was at this stage that the attack began to go seriously wrong. Strong winds blowing off the land swept the smoke screen into the face of the advancing cruisers, blinding their commanders who attempted to navigate by dead reckoning. The same wind disclosed the Inshore Squadron to the German defenders who immediately opened up a withering fire on the blockships. With their volunteer crews suffering heavy casualties, the commanders increased speed despite the poor visibility and continued groping through the narrow channels inshore, searching for the Stroom Bank buoy which directed shipping into the canal.

Commander Alfred Godsal led the assault in HMS Brilliant and it was he who stumbled into the most effective German counter-measure first. As Brilliant staggered through the murk, the lookout spotted the buoy ahead and Godsal headed directly for it, coming under even heavier fire as he did so. Passing the navigation marker at speed, the cruiser was suddenly brought to a halt with a juddering lurch, throwing men to the decks and sticking fast in deep mud well outside the harbour mouth. Before warnings could be relayed to the Sirius following up close behind, she too passed the buoy and her captain Lieutenant-Commander Henry Hardy was shocked to see Brilliant dead ahead. With no time to manoeuvre, Sirius ploughed into the port quarter of Brilliant, the blockships settling into the mud in a tangle of wreckage.

Artillery and long-range machine gun fire continued to riddle the wrecks and the combined crews were ordered to evacuate as the officers set the scuttling charges which would sink the blockships in their current, useless locations. As men scrambled down the side of the cruisers into Coastal Motor Boats which would relay them to the Offshore Squadron, destroyers moved closer to Ostend to cover the retreat and the monitors continued their heavy fire. Godsal was the last to leave, picked up by launch ML276 commanded by Lieutenant Rowley Bourke. With the main assault a complete failure, the blockading forces returned to Dover and Dunkirk to assess the disaster.

"Their Lordships will share our disappointment at the defeat of our plans by the legitimate ruse of the enemy."

Admiral Keyes' report to the Admiralty.

When the forces had reassembled and the commanders conferred, the full facts of the failed operation were revealed. The German commander of Ostend had been better prepared than his counterpart at Zeebrugge and had recognised that without the navigation buoy no night attack on Ostend could be successful without a strong familiarity with the port, which none of the British navigators possessed. However, rather than simply remove the buoy, the German commander had ordered it moved 2,400 yards east of the canal mouth into the centre of a wide expanse of sandbanks, acting as a fatal decoy for any assault force.

The Aftermath

The assault at Zeebrugge a few miles away from Ostend was more successful and the blocking of the major channel did cause some consternation amongst the German forces in Bruges. The larger raiders could no longer leave the port, but smaller ships, including most submarines, were still able to traverse via Ostend. In addition, within hours a narrow channel had also been carved through Zeebrugge too, although British intelligence did not realise this for several weeks. The defeat at Ostend did not entirely dampen the exuberant British media and public reaction to Zeebrugge, but in the Admiralty and particularly in the Allied Naval and Marine Forces the failure to completely neutralise Bruges rankled.

A second operation was planned for 10 May using the cruiser HMS Vindictive and proved more successful, but ultimately it also failed to completely close off Bruges. A third planned operation was never conducted as it rapidly became clear that the new channel carved at Zeebrugge was enough to allow access for U-boats, thus calling for an even larger double assault, which would stretch the resources of the "Allied Naval and Marine Forces" too far. British losses in the three futile attempts to close Bruges cost over 600 casualties and the loss of several ships but Bruges would remain an active raiding base for the German Navy until October 1918.

The Second Ostend Raid

The three VC's

The three VC's

The Second Ostend Raid (officially known as Operation VS) was the later of two failed attempts made during the spring of 1918 by the United Kingdom's Royal Navy to block the channels leading to the Belgian port of Ostend as a part of its conflict with the German Empire during World War I. The German Navy had used the port since 1915 as a base for their U-boat activities during the battle of the Atlantic and the strategic advantages conferred by the Belgian ports in the conflict were very important.

A successful blockade of these bases would force German submarines to operate out of more distant ports, such as Wilhelmshaven, on the German coast. This would expose them for longer to Allied countermeasures and reduce the time they could spend raiding. The ports of Ostend and Zeebrugge (which had been partially blocked in the Zeebrugge Raid three weeks previously) provided sea access via canals for the major inland port of Bruges. Bruges was used as a base for small warships and submarines. As it was 6 miles inland, it was immune to most naval artillery fire and coastal raids, providing a safe harbour for training and repair.

The Ostend Raid was largely a failure as a result of heavy German resistance and British navigational difficulties in poor weather. In anticipation of a raid, the Germans had removed the navigation buoys and without them the British had difficulty finding the narrow channel into the harbour in poor weather. When they did discover the entrance, German resistance proved too strong for the operation to be completed as originally planned: the obsolete cruiser HMS Vindictive was sunk, but only partially blocked the channel.

Despite its failure, the raid was presented in Britain as a courageous and daring gamble which came very close to success. Three Victoria Crosses and numerous other gallantry medals were awarded to sailors who participated in the operation. British forces had moderate casualties in the raid, compared to minimal German losses.

The Importance of Bruges

After the German Army captured much of Belgium following the battle of the Frontiers in 1914, the Allied forces were left holding a thin strip of coastline to the west of the Yser. The remainder of the Belgian coast came under the occupation of German Marine Divisions, including the important strategic ports of Antwerp and Bruges. Whilst Antwerp was a deep water port vulnerable to British attack from the sea, Bruges, sitting 6 miles inland, was comparatively safe from naval bombardment or coastal raids. A network of canals connected Bruges with the coast at Ostend and Zeebrugge, through which small warships such as destroyers, light cruisers and submarines could travel and find a safe harbour from which to launch raids into the English Channel and along the coasts of southeast England. U-boats could also depart from Bruges at night, cutting a day off the journey to the Western Approaches, more easily avoiding the North Sea Mine Barrage and allowing U-boat captains to gain familiarity with the net and mine defences of the English Channel, through which they had to pass to reach the main battlegrounds of the Atlantic.

In 1915–1916, the German Navy had developed Bruges from a small Flanders port into a major naval centre with large concrete bunkers to shelter U-boats, extensive barracks and training facilities for U-boat crews, and similar facilities for other classes of raiding warship. Bruges was therefore a vital asset in the German Navy's increasingly desperate struggle to prevent Britain from receiving food and materiel from the rest of the world. The significance of Bruges was not lost on British naval planners and two previous attempts to close the exit at Ostend, the smaller and narrower of the Bruges canals, had ended in failure. On 7 September 1915, four Lord Clive-class monitors of the Dover Patrol had bombarded the dockyard, while German coastal artillery returned fire. Only 14 rounds were fired by the British with the result that only part of the dockyard was set on fire. In a bombardment on 22 September 1917, the lock gates were hit causing the basin to drain at low water.

Two years passed before the next attempt on the Ostend locks. The First Ostend Raid was conducted in tandem with the similar Zeebrugge Raid led by Acting Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes on 23 April 1918; a large scale operation to block the wider canal at Zeebrugge. Both attacks largely failed, but while at Zeebrugge the operation came so close to success that it took several months for the British authorities to realise that it had been unsuccessful, at Ostend the attack had ended catastrophically. Both blockships intended to close off the canal had grounded over half a mile from their intended location and been scuttled by their crews under heavy artillery and long-range small arms fire, which caused severe casualties. Thus while Zeebrugge seemed to be blocked entirely, Ostend was open wide, nullifying any success which might have been achieved at the other port.

The Plan

As British forces on the southeast coast of Britain regrouped, re-grouped and repaired following heavy losses at Zeebrugge, Keyes planned a return to Ostend with the intention of blocking the canal and consequently severing Bruges from the sea, closing the harbour and trapping the 18 U-boats and 25 destroyers present for months to come. Volunteers from amongst the force which had failed in April aided the planning with advice based on bitter experience. Among these volunteers were Lieutenant-Commander Henry Hardy of HMS Sirius, Commander Alfred Godsal, former captain of HMS Brilliant, and Brilliant's first lieutenant Victor Crutchley. These officers approached Commodore Hubert Lynes and Admiral Roger Keyes with a refined plan for a second attempt to block the port. Other officers came forward to participate as well and Keyes and Lynes devised an operational plan to attack the canal mouth at Ostend once more.

Two obsolete cruisers—the aged HMS Sappho and the battered veteran of Zeebrugge, HMS Vindictive—were fitted out for the operation by having their non-essential equipment stripped out, their essential equipment reinforced and picked crews selected from volunteers. The ships' forward ballast tanks were filled with concrete to both protect their bows during the attack, and act as a more lasting obstacle once sunk. Vindictive was commanded by Godsal; her six officers and 48 crew were all volunteer veterans of the previous failed attempt by Brilliant. The two sacrificial cruisers were, as with the previous attack, accompanied by four heavy monitors under Keyes' command, eight destroyers under Lynes in HMS Faulknor and five motor launches. Like the blockships, the launches were all crewed by volunteers; mostly veterans of previous operations against the Belgian ports.

The plan was similar to the failed operation of three weeks previously. Weather dependent, under cover of a smoke screen, aerial bombardment and offshore artillery, the blockships would steam directly into the channel, turn sideways and scuttle themselves. Their advance would be covered by artillery fire against German shore positions from the heavy monitors at distance and at closer range by gunfire from the destroyers. This cover was vital because Ostend was protected by a very strong 11 inch gun position known as the Tirpitz battery. Once the operation had been concluded, the motor launches would draw along the seaward side of the blockships, remove the surviving crews and take them to the monitors for passage back to Britain. This operation was to thoroughly block the channel, and — coupled with the blockage at Zeebrugge (which the British authorities believed to be fully closed) — was to prevent use of Bruges by German raiding craft for months to come.

Attack

All preparations for the operation were completed by the first week of May and on 9 May the weather was nearly perfect for the attack. The British armada had collected at Dunkirk in Allied-held France and departed port shortly after dark. Two minutes after midnight, the force suffered a setback when Sappho suffered a minor boiler explosion and had to return to Dunkirk, unable to complete the journey. Although this accident halved the ability of the force to block Ostend, Lynes decided to continue the operation, and at 01:30, the force closed on the port, making the final preparations for the assault. Torpedoes fired from motor launches demolished machine gun posts on the ends of the piers marking the canal, beginning the attack. Ten heavy bombers of the newly formed Royal Air Force then dropped incendiary bombs on German positions, but did not cause significant damage. In spite of the fog, air operations continued as planned under the overall direction of Brigadier-General Charles Lambe. At the same time as the aerial bombardment began, the long range artillery of the Royal Marine Artillery opened fire on Ostend from Allied positions around the Belgian town of Ypres.

"The star-shells paled and were lost as they sank in it; the beams of the searchlights seemed to break off short upon its front. It blinded the observers of the great batteries when suddenly, upon the warning of the explosions, the guns roared into action. It was then that those on the destroyers became aware that what had seemed to be merely smoke was wet and cold, that the rigging was beginning to drip, that there were no longer any stars – a sea-fog had come on."

British Admiralty Statement on the Ostend Raid.

In preparation for the attack, Godsal and Lynes had carefully consulted available charts of Ostend following the previous operation's failure caused by German repositioning of navigation buoys. This careful study was, however, rendered worthless by a sudden fog which obliterated all sight of the shore. Steaming back and forth across the harbour entrance in the fog as the monitors and German shore batteries engaged in a long range artillery duel over the lost cruiser, Godsal looked for the piers marking the entrance to the canal. As he searched, two German torpedo boats sailed from Ostend to intercept the cruiser, but in the heavy fog they collided and, disabled, limped back to shore. During this period, Godsal's motor launches lost track of the cruiser in the murk, and it was not until the third pass that Vindictive found the entrance, accompanied by only one of the launches. Heading straight into the mouth of the canal, guided by a flare dropped by the launch, Vindictive became an instant target of the German batteries and was badly damaged, the shellfire exacerbating the damage suffered in the earlier Zeebrugge Raid and seriously damaging Vindictive's port propeller.

Alfred Godsal intended to swing Vindictive broadside on into the channel mouth, but as he ordered the turn, the right screw broke down completely, preventing the cruiser from fully turning. Before this was realised on the cruiser's bridge, a shell fired from a gun battery on shore struck Commander Godsal directly, killing him instantly and shattering the bridge structure. Most of the bridge crew were killed or wounded by the blast, including First Lieutenant Victor Crutchley, who staggered to the wheel and attempted to force the ship to make the full turn into the channel. The damaged propeller made this manoeuvre impossible and the drifting cruiser floated out of the channel and became stuck on a sandbank outside, only partially obscuring the entranceway.

Evacuation of HMS Vindictive

Realising that further manoeuvring would be pointless, Crutchley ordered the charges to be blown and the ship evacuated.As Engineer-Lieutenant William Bury prepared to detonate the scuttling charges, Crutchley took a survey of the ship and ordered all survivors to take to the boats on the seaward side of the wreck. As men scrambled down the ship's flank away from the shells and machine-gun bullets spitting from the harbour entrance, Crutchley made a final survey with an electric torch looking for wounded men amongst the dead on the decks. Satisfied that none alive remained aboard, he too leapt onto the deck of a motor launch bobbing below. The rescue mission itself, however, was not going as planned. Of the five motor launches attached to the expedition, only one had remained with the cruiser in the fog; ML254 commanded by Lieutenant Geoffrey Drummond. The launch—like the cruiser—was riddled with bullets; her commander was wounded and her executive officer dead. Despite her sheltered position behind the cruiser, fire from shore continued to enfilade the launch and a number of those aboard, including Lieutenant Bury, suffered broken ankles as they jumped onto the heaving deck.

ML254 then began slowly to leave the harbour mouth, carrying 38 survivors of Vindictive's 55 crewmen huddled on deck, where they remained exposed to machine gun fire from the shore. As Drummond turned his boat seawards and proceeded back to the offshore squadron which was still engaged in an artillery duel with the German defenders, one of the missing launches, ML276 passed her, having caught up with the lost cruiser at this late stage. Drummond called to ML276's commander—Lieutenant Rowley Bourke—that he believed there were still men in the water and Bourke immediately entered the harbour to search for them. Drummond's launch proceeded to the rendezvous with the destroyer HMS Warwick, overweight and sinking, so severe was the damage she had suffered.

Hearing cries, Bourke entered the harbour but could not identify the lost men. Despite heavy machine gun and artillery fire, Bourke returned to the scene of the wreck four times before they discovered two sailors and Vindictive's badly wounded navigation officer Sir John Alleyne clinging to an upturned boat. Hauling the men aboard, Bourke turned for the safety of the open sea, but as he did, two 6 inch shells struck the launch, smashing the lifeboat and destroying the compressed air tanks. This stalled the engines and caused a wave of highly corrosive acid to wash over the deck, causing severe damage to the launch's hull and almost suffocating the unconscious Alleyne. Under heavy fire, the boat staggered out of the harbour and was taken under tow by another late-arriving motor launch. After the operation, Bourke's launch was discovered to have 55 bullet and shrapnel holes.

Offshore, as Warwick's officers, Keyes' staff and the survivors of Vindictive gathered on the destroyer's deck to discuss the operation, an enormous explosion rocked the ship causing her to list severely. Warwick had struck one of the defensive mines off Ostend and was now in danger of sinking herself. The destroyer HMS Velox was lashed alongside and survivors from Warwick, Vindictive and ML254 transferred across to the sound ship. This ragged ensemble did not reach Dover until early the following morning, with Warwick still afloat. British casualties were reported in the immediate aftermath as being eight dead, ten missing and 29 wounded. German losses were three killed and eight wounded.

Aftermath

Despite German claims that the blockage did not impede their operations, the operation to close the Ostend canal seemed to have been at least partially successful. The channel was largely blocked and so Bruges was ostensibly closed off from the open sea, even if the position of the blockship meant that smaller ships could get through. In fact, the entire operation had been rendered moot before it even began, due to events at the wider canal in Zeebrugge. British assessments of that operation had proven optimistic and the channel there had not been properly closed. Small coastal submarines of the UC class had been able to pass through the channel as early as the morning after the Zeebrugge Raid and German naval engineers were able to dredge channels around the blockages at both ports over the coming weeks.

At Ostend, Vindictive did prevent larger warships passing through the channel, although smaller craft could still come and go at will. The larger warships in Bruges were trapped there for the remaining months of the war; the town was captured by the Allies in October 1918. The blockages at Ostend and Zeebrugge took several years to clear completely, not being totally removed until 1921. On a strategic scale the effects of the raids at Ostend and Zeebrugge on the battle of the Atlantic were negligible. Despite this, in Britain the Ostend Raid was feted as a success. Three Victoria Crosses and a host of lesser awards were given to the men involved. The Admiralty presented it as a fine example of daring and careful planning from the Royal Navy, providing a valuable morale boost at one of the most critical moments of the war.

Source - Wikipedia

Despite German claims that the blockage did not impede their operations, the operation to close the Ostend canal seemed to have been at least partially successful. The channel was largely blocked and so Bruges was ostensibly closed off from the open sea, even if the position of the blockship meant that smaller ships could get through. In fact, the entire operation had been rendered moot before it even began, due to events at the wider canal in Zeebrugge. British assessments of that operation had proven optimistic and the channel there had not been properly closed. Small coastal submarines of the UC class had been able to pass through the channel as early as the morning after the Zeebrugge Raid and German naval engineers were able to dredge channels around the blockages at both ports over the coming weeks.

At Ostend, Vindictive did prevent larger warships passing through the channel, although smaller craft could still come and go at will. The larger warships in Bruges were trapped there for the remaining months of the war; the town was captured by the Allies in October 1918. The blockages at Ostend and Zeebrugge took several years to clear completely, not being totally removed until 1921. On a strategic scale the effects of the raids at Ostend and Zeebrugge on the battle of the Atlantic were negligible. Despite this, in Britain the Ostend Raid was feted as a success. Three Victoria Crosses and a host of lesser awards were given to the men involved. The Admiralty presented it as a fine example of daring and careful planning from the Royal Navy, providing a valuable morale boost at one of the most critical moments of the war.

Source - Wikipedia

Second Lieutenant

Curtis Matthew De Rochie

27th Sqdn. Royal Flying Corps

14th July 1917

Row A. 10.

Son of Curtis Peter DeRochie and Catherine (Kate) Murphy of Cornwall, Ontario, Canada, brother to Loretta DeRochie Mahoney and Merchant Michael Mahoney, Uncle to Anne Kathleen Mahoney Summers and Charles Curtis Mahoney

"The Uncle we never knew, whose memory was never forgotten."

Remembered by his great nieces and nephews in the Mahoney and DeRochie families

Picture courtesy of Trish Mahoney-Laska, great-niece.

Curtis Matthew De Rochie

27th Sqdn. Royal Flying Corps

14th July 1917

Row A. 10.

Son of Curtis Peter DeRochie and Catherine (Kate) Murphy of Cornwall, Ontario, Canada, brother to Loretta DeRochie Mahoney and Merchant Michael Mahoney, Uncle to Anne Kathleen Mahoney Summers and Charles Curtis Mahoney

"The Uncle we never knew, whose memory was never forgotten."

Remembered by his great nieces and nephews in the Mahoney and DeRochie families

Picture courtesy of Trish Mahoney-Laska, great-niece.

Commander

Alfred Edmund Godsal, D. S. O., Croix de Guerre (France).

H.M.S. "Vindictive" Royal Navy

10th May 1918, aged 33.

Row A. 17.

Son of Major and Mrs Philip Godsal, Iscoyd Park, Whitchurch, Salop

He died as Captain of HMS Vindictive in the Second Ostend Raid, having previously been in command of HMS Brilliant in the First Ostend Raid on 23 April 1918.

Picture courtesy of Brigadier D H Godsal MBE DL, great nephew of Commander Godsal

Alfred Edmund Godsal, D. S. O., Croix de Guerre (France).

H.M.S. "Vindictive" Royal Navy

10th May 1918, aged 33.

Row A. 17.

Son of Major and Mrs Philip Godsal, Iscoyd Park, Whitchurch, Salop

He died as Captain of HMS Vindictive in the Second Ostend Raid, having previously been in command of HMS Brilliant in the First Ostend Raid on 23 April 1918.

Picture courtesy of Brigadier D H Godsal MBE DL, great nephew of Commander Godsal