LONGUENESSE (ST. OMER) SOUVENIR CEMETERY

Pas De Calais

France

GPS Coordinates Latitude: 50.73114 Longitude: 2.25023

Roll of Honour

Listed by Surname

Location Information

St. Omer is a large town 45 kilometres south-east of Calais. Longuenesse is a commune on the southern outskirts of St. Omer.

The Cemetery is approximately 3 kilometres from St Omer, beside the Wizernes (Abbeville) road (the D928), at its junction with the Rue des Bruyeres.

Visiting Information

Car parking is available at the front of the main entrance but is restricted. However, there is a large car park at the rear of the cemetery and access can be made via the service entrance.

Wheelchair access to this cemetery is possible with some difficulty.

Historical Information

St. Omer was the General Headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force from October 1914 to March 1916. Lord Roberts died there in November 1914. The town was a considerable hospital centre with the 4th, 10th, 7th Canadian, 9th Canadian and New Zealand Stationary Hospitals, the 7th, 58th (Scottish) and 59th (Northern) General Hospitals, and the 17th, 18th and 1st and 2nd Australian Casualty Clearing Stations all stationed there at some time during the war. St. Omer suffered air raids in November 1917 and May 1918, with serious loss of life.

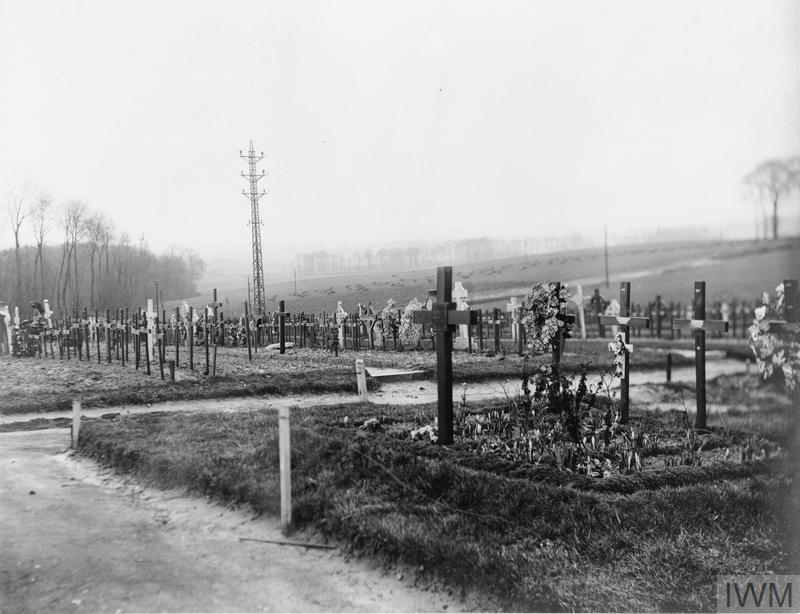

The cemetery takes its names from the triangular cemetery of the St. Omer garrison, properly called the Souvenir Cemetery (Cimetiere du Souvenir Francais) which is located next to the War Cemetery.

The Commonwealth section of the cemetery contains 2,874 Commonwealth burials of the First World War (6 unidentified), with special memorials commemorating 23 men of the Chinese Labour Corps whose graves could not be exactly located. Second World War burials number 403, (93 unidentified). Within the Commonwealth section there are also 34 non-war burials and 239 war graves of other nationalities.

Total Burials: 3,548.

World War One Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 2,484, Germany 182, Australia 156, Canada 150, New Zealand 53, South Africa 14, India 6. Total 3,055.

World War Two Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 289, Czechoslovakia 27, Canada 11, Australia 8, Poland 4, New Zealand 3. Total 342.

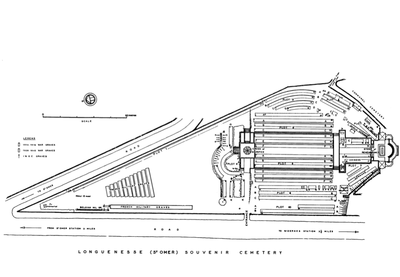

The cemetery was designed by Sir Herbert Baker and Arthur James Scott Hutton

St. Omer is a large town 45 kilometres south-east of Calais. Longuenesse is a commune on the southern outskirts of St. Omer.

The Cemetery is approximately 3 kilometres from St Omer, beside the Wizernes (Abbeville) road (the D928), at its junction with the Rue des Bruyeres.

Visiting Information

Car parking is available at the front of the main entrance but is restricted. However, there is a large car park at the rear of the cemetery and access can be made via the service entrance.

Wheelchair access to this cemetery is possible with some difficulty.

Historical Information

St. Omer was the General Headquarters of the British Expeditionary Force from October 1914 to March 1916. Lord Roberts died there in November 1914. The town was a considerable hospital centre with the 4th, 10th, 7th Canadian, 9th Canadian and New Zealand Stationary Hospitals, the 7th, 58th (Scottish) and 59th (Northern) General Hospitals, and the 17th, 18th and 1st and 2nd Australian Casualty Clearing Stations all stationed there at some time during the war. St. Omer suffered air raids in November 1917 and May 1918, with serious loss of life.

The cemetery takes its names from the triangular cemetery of the St. Omer garrison, properly called the Souvenir Cemetery (Cimetiere du Souvenir Francais) which is located next to the War Cemetery.

The Commonwealth section of the cemetery contains 2,874 Commonwealth burials of the First World War (6 unidentified), with special memorials commemorating 23 men of the Chinese Labour Corps whose graves could not be exactly located. Second World War burials number 403, (93 unidentified). Within the Commonwealth section there are also 34 non-war burials and 239 war graves of other nationalities.

Total Burials: 3,548.

World War One Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 2,484, Germany 182, Australia 156, Canada 150, New Zealand 53, South Africa 14, India 6. Total 3,055.

World War Two Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 289, Czechoslovakia 27, Canada 11, Australia 8, Poland 4, New Zealand 3. Total 342.

The cemetery was designed by Sir Herbert Baker and Arthur James Scott Hutton

Entrance to Cemetery and Cemetery Map

Pictures © Werner Van Caneghem

Commonwealth World War One

Pictures © Werner Van Caneghem

3697 Lance Corporal Cecil Reginald Noble, V. C.

"C" Company, 2nd Bn. Rifle Brigade

died of wounds 13th March 1915, aged 23.

Plot I. A. 57.

Son of Hannah Noble, of "Ferndean," 172, Capstone Rd., Bournemouth, and the late Frederick Leopold Noble.

His headstone bears the inscription " Keeping We Leave Thee Dear Until We Meet Again"

Citation:

An extract from the Supplement to the London Gazette of 27th April, 1915 (No. 29146) records the award of the V.C. to this N.C.O. and to C.S.M. H. Daniels "For most conspicuous bravery on 12th March, 1915, at Neuve-Chapelle, when their battalion was impeded in the advance to attack by wire entanglements, and subjected to a very severe machine-gun fire, these two men voluntarily rushed in front and succeeded in cutting the wires."

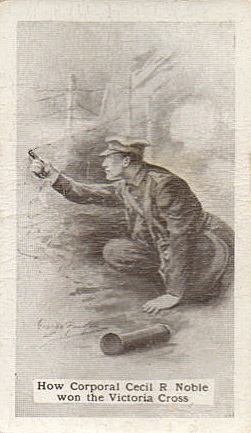

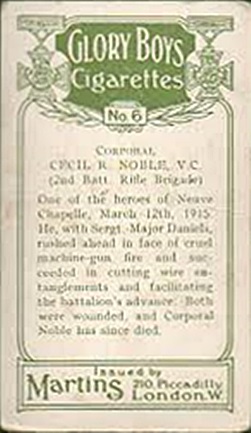

Cecil Noble's bravery was immortalised on this 1916 Martins "Glory Boys" Cigarette Card. (left) and a Cohen-Weenen "Victoria Cross Heroes card (right)

Other Nationalities

Pictures © Werner Van Caneghem

Images in this gallery © Geerhard Joos

Shot at Dawn

28719 Private, James Cuthbert, 9th Bn. Cheshire Regiment, executed for disobedience, 6th May 1916, aged 20. Son of Mrs. Edith Cuthbert, of 61, Webster Street, Oldham, Lancs. Plot V. F. 71.

On the night of 14-15 April 1916, a wiring party was due to go out into No-man’s-land: it comprised a sergeant, a corporal & 8 men under the command of Second Lieut Kenyon. There seems to have been a general agreement amongst the men — almost certainly encouraged by the NCOs — that it was dangerously light & that they should all refuse to go out, Cuthbert saying at one stage that he would rather be shot than go out wiring that night. Second Lieut Kenyon failed to get the men out, so the company commander ordered the whole party to follow him, advising the recalcitrant men of the penalty for disobedience, but Cuthbert & 2 other privates nonetheless remained behind.

All 3 were found Guilty at court-martial & sentenced to death. That on Cuthbert, who was said to be a source of corruption in the regiment, was confirmed by Haig, while the sentences on the other 2 were commuted.

The widespread reluctance to go out in the wiring party seems to have been well-founded, for Second Lieut Kenyon was shot & wounded, while the author of the War Diary for the following night mentions the shine of the moon making it too light for wiring in front. (Corns, pp. 128-130)

32559 Private, Charles Bain Nicholson, 8th Bn. Yorks and Lancaster Regiment, executed for desertion, 27th October 1917, aged 19. Twin son of Alexander and Catherine Nicholson, of 11, Leven St., Middlesbrough. Plot IV. E. 66.

In June 1917, he deserted & was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment with hard labour — which was commuted to 90 days’ Field Punishment No 1. Before completion of sentence, Nicholson again went absent, for which 2 years' imprisonment with hard labour was imposed — the sentence being later suspended. However he went absent yet again, only to be arrested & brought once more to trial. By a sad coincidence, his twin brother was killed in action 2 days after what was to be Nicholson’s final trial. (Putkowski, pp.211-212)

8752 Private, Isaac Reid, 2nd Bn. Scots Guards, executed for desertion, 9th April 1915. Plot III. B. 26.

He deserted during the attack on Neuve Chapelle & was discovered in the rear a few hours later. Unrepresented at trial, Reid (who had given inconsistent answers when previously questioned) admitted losing his head & expressed regret. His character was described as very good, but it was further stated that he was not a good fighter. Mercy was recommended, but in vain. (Putkowski, p.40)

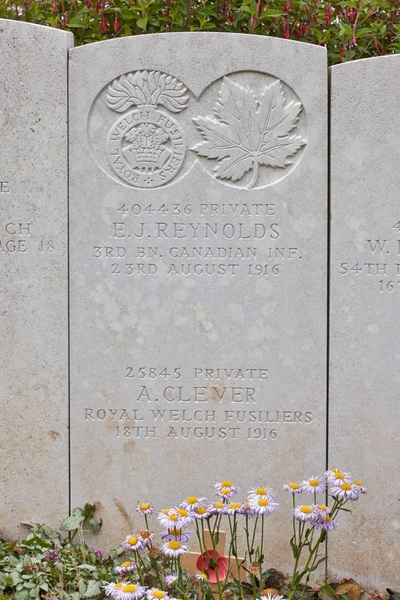

404436 Private, E. J. Reynolds, 3rd Bn. Canadian Infantry, executed for desertion, 23rd August 1916. Plot IV. A. 39.

He ‘fell out’ on the way to the trenches. Throwing down his rifle, Reynolds insisted that he would not go even at the point of a bayonet. At the trial, Reynolds’ captain, the platoon commander & sergeant all testified to the courage formerly shown by the accused — but in vain. (Putkowski, pp102-103)

7552 Lance Serjeant, William Walton, 2nd Bn. King's Royal Rifle Corps, executed for desertion, 23rd March 1915, aged 26. Son of Mrs. H. Walton, of 5, Pelham Street, Hanley, Staffs. Plot I. A. 68.

He was a Reservist, who had served 2 years in India.

On 1 Nov 1914, his battalion was under heavy fire near Ypres, when it was suddenly called to reinforce another battalion that had been overrun. Walton was present when his company fell in, but was not seen again till 3 Mar 1915.

On or about 18 Dec 1914, he arrived at the house of a Frenchman in Arques — tired, wet through, with traces of wounds, but with no rifle or equipment — & sought a bed for the night. He stayed there for some time, even after the Gendarmerie were informed of his presence on 23 Dec.

At his arrest on 3 Mar, Walton seemed ‘half-dazed’ & unwilling or incapable when dealing with simple questions. In a statement made later the same day, he said ‘I have been suffering a nervous breakdown ever since I was wounded’.

At trial, Walton testified to say that he had led his company forward under heavy fire; had then been given charge of some stragglers by an officer; had been wounded, spending some days in a trench; & thereafter had been in Cassel, Arques, & Hazebrouck, all the while trying to find his battalion.

No evidence was adduced as to his state of mind, not even by Walton himself.

After conviction, the Brigade commander was advised by the Chaplain that W’s mind seemed unhinged, & that Walton seemed incapable of understanding his situation, & therefore asked that the condemned man be kept under observation. He was not, but was examined by 3 RAMC officers who reported that Walton was of sound mind. (Corns, pp 314-316)

Gallery of Shot at Dawn Graves © Geerhard Joos

28719 Private, James Cuthbert, 9th Bn. Cheshire Regiment, executed for disobedience, 6th May 1916, aged 20. Son of Mrs. Edith Cuthbert, of 61, Webster Street, Oldham, Lancs. Plot V. F. 71.

On the night of 14-15 April 1916, a wiring party was due to go out into No-man’s-land: it comprised a sergeant, a corporal & 8 men under the command of Second Lieut Kenyon. There seems to have been a general agreement amongst the men — almost certainly encouraged by the NCOs — that it was dangerously light & that they should all refuse to go out, Cuthbert saying at one stage that he would rather be shot than go out wiring that night. Second Lieut Kenyon failed to get the men out, so the company commander ordered the whole party to follow him, advising the recalcitrant men of the penalty for disobedience, but Cuthbert & 2 other privates nonetheless remained behind.

All 3 were found Guilty at court-martial & sentenced to death. That on Cuthbert, who was said to be a source of corruption in the regiment, was confirmed by Haig, while the sentences on the other 2 were commuted.

The widespread reluctance to go out in the wiring party seems to have been well-founded, for Second Lieut Kenyon was shot & wounded, while the author of the War Diary for the following night mentions the shine of the moon making it too light for wiring in front. (Corns, pp. 128-130)

32559 Private, Charles Bain Nicholson, 8th Bn. Yorks and Lancaster Regiment, executed for desertion, 27th October 1917, aged 19. Twin son of Alexander and Catherine Nicholson, of 11, Leven St., Middlesbrough. Plot IV. E. 66.

In June 1917, he deserted & was sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment with hard labour — which was commuted to 90 days’ Field Punishment No 1. Before completion of sentence, Nicholson again went absent, for which 2 years' imprisonment with hard labour was imposed — the sentence being later suspended. However he went absent yet again, only to be arrested & brought once more to trial. By a sad coincidence, his twin brother was killed in action 2 days after what was to be Nicholson’s final trial. (Putkowski, pp.211-212)

8752 Private, Isaac Reid, 2nd Bn. Scots Guards, executed for desertion, 9th April 1915. Plot III. B. 26.

He deserted during the attack on Neuve Chapelle & was discovered in the rear a few hours later. Unrepresented at trial, Reid (who had given inconsistent answers when previously questioned) admitted losing his head & expressed regret. His character was described as very good, but it was further stated that he was not a good fighter. Mercy was recommended, but in vain. (Putkowski, p.40)

404436 Private, E. J. Reynolds, 3rd Bn. Canadian Infantry, executed for desertion, 23rd August 1916. Plot IV. A. 39.

He ‘fell out’ on the way to the trenches. Throwing down his rifle, Reynolds insisted that he would not go even at the point of a bayonet. At the trial, Reynolds’ captain, the platoon commander & sergeant all testified to the courage formerly shown by the accused — but in vain. (Putkowski, pp102-103)

7552 Lance Serjeant, William Walton, 2nd Bn. King's Royal Rifle Corps, executed for desertion, 23rd March 1915, aged 26. Son of Mrs. H. Walton, of 5, Pelham Street, Hanley, Staffs. Plot I. A. 68.

He was a Reservist, who had served 2 years in India.

On 1 Nov 1914, his battalion was under heavy fire near Ypres, when it was suddenly called to reinforce another battalion that had been overrun. Walton was present when his company fell in, but was not seen again till 3 Mar 1915.

On or about 18 Dec 1914, he arrived at the house of a Frenchman in Arques — tired, wet through, with traces of wounds, but with no rifle or equipment — & sought a bed for the night. He stayed there for some time, even after the Gendarmerie were informed of his presence on 23 Dec.

At his arrest on 3 Mar, Walton seemed ‘half-dazed’ & unwilling or incapable when dealing with simple questions. In a statement made later the same day, he said ‘I have been suffering a nervous breakdown ever since I was wounded’.

At trial, Walton testified to say that he had led his company forward under heavy fire; had then been given charge of some stragglers by an officer; had been wounded, spending some days in a trench; & thereafter had been in Cassel, Arques, & Hazebrouck, all the while trying to find his battalion.

No evidence was adduced as to his state of mind, not even by Walton himself.

After conviction, the Brigade commander was advised by the Chaplain that W’s mind seemed unhinged, & that Walton seemed incapable of understanding his situation, & therefore asked that the condemned man be kept under observation. He was not, but was examined by 3 RAMC officers who reported that Walton was of sound mind. (Corns, pp 314-316)

Gallery of Shot at Dawn Graves © Geerhard Joos

Images in gallery below © Nicholas Philpot

The graves of Staff Nurse Agnes Murdoch Climie and Sister Mabel Lee Milne of the Territorial Force Nursing Service, as well as Daisy Kathleen Mary Coles and Elizabeth Thomson of the Voluntary Aid Detachments, killed by enemy aircraft 30th September 1917, erected by officers and nursing staff of the No. 4 Stationary Hospital [or the 58th (Scottish) General Hospital] at Longuenesse in Souvenir Cemetery. © The rights holder (IWM Q 108207)

Doing their Bit - The Voluntary Aid Detachment

by Janine Lawrence

Over the centuries the history of our country has been littered with governmental mistakes and mishaps. How refreshing then, that in 1908 the new Secretary of State for War, Lord Haldane, undertook reforms in the army which were to have far-reaching effects.

He established a new part-time army of volunteers who were fully-trained soldiers in full-time jobs and who were organised on a county system. This Territorial Force became jokingly known as the 'Saturday Night Soldiers' as the young men who joined were taught to shoulder arms at weekly meetings and drills. They even attended summer camp and many 'Terriers' were at camp when war was declared in August 1914.

In 1909, with unbelievable foresight, the War Office issued a 'Scheme for the Organisation of Voluntary Aid in England and Wales' which recognised the need to provide sufficient medical backup to supplement the Territorial Force in the event of war. Ultimate efficiency would not be realised unless all voluntary aid was co-ordinated and the Territorial Associations were directed to entrust the work to the British Red Cross which had also adopted the county system of organisation. They joined up with the Order of St John of Jerusalem and thus, the organisation known as the Voluntary Aid Detachment was born.

Detachments were divided into those for men and those for women. Men's detachments numbered 56 lead by a commandant and comprising a medical officer, a quartermaster, a pharmacist and four section leaders each responsible for 12 men. They were usually responsible for transport and converting suitable buildings into hospitals and clearing stations and would also act as stretcher-bearers and male nurses if required. After enrolment the men studied first aid and were lectured in the various duties connected with transport and camps.

The women's detachments were less than half the strength of the men. They were also led by a commandant, who could either be male or female and not necessarily a doctor, a quartermaster, a trained nurse as a lady superintendent and 20 women of whom four had to be qualified cooks. It was felt the women's detachments would be better served to the 'less arduous' task of forming railway rest stations where they could prepare and serve meals for sick and wounded soldiers. It was obvious they were seen more as domestic assistants than nurses! However, they were given lectures in first aid, home nursing, hygiene and cookery and were occasionally given training in infirmaries. They were taught to identify suitable buildings for use as temporary hospitals and how to obtain equipment and supplies.

Within a year membership numbered somewhere around 6000 with over 2,500 detachments. These numbers increased considerably after the outbreak of war in 1914 and numbers rose to over 74,000, two-thirds of whom were women and girls.

As men were called away to answer their country's call it fell upon the women to fill their shoes in whatever way they could. Initially it was mostly middle-class women who were eager to 'do their bit' and they took on roles such as ambulance drivers, welfare officers, fundraisers, civil defence workers and even letter writers for the illiterate. It is interesting to note that the novelist, Agatha Christie was a VAD and worked in a hospital pharmacy where she learned about poisons!

The military authorities were reluctant at this early stage to accept VADs on the front line, perhaps thinking that the battlefield was no place for a woman. However, this restriction was lifted in 1915 and women volunteers over the age of twenty three and with more than three months experience were allowed to go to the Western Front, Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. Eventually VAD's were also sent to the Eastern Front.

Before the outbreak of war some VADs had taken short nursing courses for which they were awarded certificates. Qualified nurses had undertaken three years training and were understandably suspicious of these short courses, referring to the volunteers as 'ignorant amateurs'. Quarrels broke out and there are even reports of open conflict before the new spirit of unity in time of war was felt and working together for mutual benefit was the order of the day.

The VAD's became very active in the war effort using influence to transport themselves to the conflicts in France to care for the sick and wounded and thus carving out for themselves a clear role as nurses or orderlies in hospitals at home and in the theatres of war. By 1916 their numbers had increased to 80,000.

In 1917 clear regulations were laid down by the British Red Cross which governed the employment of nursing VAD's in military hospitals. Age limits were specified and volunteers should be between 21 and 48 years of age for home service and 23 and 42 for foreign. They were to be appointed for one month on probation during which time they were assessed for suitability by the matron. They then had to sign an agreement to serve for six months or the duration of the war, at home or abroad. Salary would be £20 per annum rising to £22.10.0 for those who signed on for another six months at the end of their current contract. Increments of a further £2.10.0 would be paid every six months until probationers reached the maximum of £30 per annum.

It was also laid down that VAD's should work under fully trained nurses with duties including sweeping, dusting, polishing, cleaning, washing patients' crockery, sorting linen and any nursing duties allotted by the matron.

Meanwhile, VAD hospitals were being set up in Blighty and were mostly located in large houses loaned for the purpose by their owners. Gustard Wood at Wheathampstead and The Bury at King's Walden are just two Hertfordshire premises used. The Council School in Royston and the former mental hospital, Napsbury in Colney Heath are examples of institutes put into service.

These hospitals received the sum of three shillings per day per patient from the War Office and were expected to raise additional funds themselves. As everyone was keen to be seen to help the war effort this was not difficult and local newspapers regularly featured lists of donations received - obviously anonymity did not seem to be the case!

Many women returning home after the conflict ended undertook formal nurse training and registration with the General Nursing Council. Others tried to pick up the threads of their former lives. What must be certain is that life could never have been the same for any of them again. The sight, smell and fear of war must have been imprinted on every mind bringing about a change in the lives of women which would grow and grow over the following years.

Our thanks to Janine Lawrence for permission to use this article.

© Janine Lawrence

by Janine Lawrence

Over the centuries the history of our country has been littered with governmental mistakes and mishaps. How refreshing then, that in 1908 the new Secretary of State for War, Lord Haldane, undertook reforms in the army which were to have far-reaching effects.

He established a new part-time army of volunteers who were fully-trained soldiers in full-time jobs and who were organised on a county system. This Territorial Force became jokingly known as the 'Saturday Night Soldiers' as the young men who joined were taught to shoulder arms at weekly meetings and drills. They even attended summer camp and many 'Terriers' were at camp when war was declared in August 1914.

In 1909, with unbelievable foresight, the War Office issued a 'Scheme for the Organisation of Voluntary Aid in England and Wales' which recognised the need to provide sufficient medical backup to supplement the Territorial Force in the event of war. Ultimate efficiency would not be realised unless all voluntary aid was co-ordinated and the Territorial Associations were directed to entrust the work to the British Red Cross which had also adopted the county system of organisation. They joined up with the Order of St John of Jerusalem and thus, the organisation known as the Voluntary Aid Detachment was born.

Detachments were divided into those for men and those for women. Men's detachments numbered 56 lead by a commandant and comprising a medical officer, a quartermaster, a pharmacist and four section leaders each responsible for 12 men. They were usually responsible for transport and converting suitable buildings into hospitals and clearing stations and would also act as stretcher-bearers and male nurses if required. After enrolment the men studied first aid and were lectured in the various duties connected with transport and camps.

The women's detachments were less than half the strength of the men. They were also led by a commandant, who could either be male or female and not necessarily a doctor, a quartermaster, a trained nurse as a lady superintendent and 20 women of whom four had to be qualified cooks. It was felt the women's detachments would be better served to the 'less arduous' task of forming railway rest stations where they could prepare and serve meals for sick and wounded soldiers. It was obvious they were seen more as domestic assistants than nurses! However, they were given lectures in first aid, home nursing, hygiene and cookery and were occasionally given training in infirmaries. They were taught to identify suitable buildings for use as temporary hospitals and how to obtain equipment and supplies.

Within a year membership numbered somewhere around 6000 with over 2,500 detachments. These numbers increased considerably after the outbreak of war in 1914 and numbers rose to over 74,000, two-thirds of whom were women and girls.

As men were called away to answer their country's call it fell upon the women to fill their shoes in whatever way they could. Initially it was mostly middle-class women who were eager to 'do their bit' and they took on roles such as ambulance drivers, welfare officers, fundraisers, civil defence workers and even letter writers for the illiterate. It is interesting to note that the novelist, Agatha Christie was a VAD and worked in a hospital pharmacy where she learned about poisons!

The military authorities were reluctant at this early stage to accept VADs on the front line, perhaps thinking that the battlefield was no place for a woman. However, this restriction was lifted in 1915 and women volunteers over the age of twenty three and with more than three months experience were allowed to go to the Western Front, Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. Eventually VAD's were also sent to the Eastern Front.

Before the outbreak of war some VADs had taken short nursing courses for which they were awarded certificates. Qualified nurses had undertaken three years training and were understandably suspicious of these short courses, referring to the volunteers as 'ignorant amateurs'. Quarrels broke out and there are even reports of open conflict before the new spirit of unity in time of war was felt and working together for mutual benefit was the order of the day.

The VAD's became very active in the war effort using influence to transport themselves to the conflicts in France to care for the sick and wounded and thus carving out for themselves a clear role as nurses or orderlies in hospitals at home and in the theatres of war. By 1916 their numbers had increased to 80,000.

In 1917 clear regulations were laid down by the British Red Cross which governed the employment of nursing VAD's in military hospitals. Age limits were specified and volunteers should be between 21 and 48 years of age for home service and 23 and 42 for foreign. They were to be appointed for one month on probation during which time they were assessed for suitability by the matron. They then had to sign an agreement to serve for six months or the duration of the war, at home or abroad. Salary would be £20 per annum rising to £22.10.0 for those who signed on for another six months at the end of their current contract. Increments of a further £2.10.0 would be paid every six months until probationers reached the maximum of £30 per annum.

It was also laid down that VAD's should work under fully trained nurses with duties including sweeping, dusting, polishing, cleaning, washing patients' crockery, sorting linen and any nursing duties allotted by the matron.

Meanwhile, VAD hospitals were being set up in Blighty and were mostly located in large houses loaned for the purpose by their owners. Gustard Wood at Wheathampstead and The Bury at King's Walden are just two Hertfordshire premises used. The Council School in Royston and the former mental hospital, Napsbury in Colney Heath are examples of institutes put into service.

These hospitals received the sum of three shillings per day per patient from the War Office and were expected to raise additional funds themselves. As everyone was keen to be seen to help the war effort this was not difficult and local newspapers regularly featured lists of donations received - obviously anonymity did not seem to be the case!

Many women returning home after the conflict ended undertook formal nurse training and registration with the General Nursing Council. Others tried to pick up the threads of their former lives. What must be certain is that life could never have been the same for any of them again. The sight, smell and fear of war must have been imprinted on every mind bringing about a change in the lives of women which would grow and grow over the following years.

Our thanks to Janine Lawrence for permission to use this article.

© Janine Lawrence