Villers-Bretonneux Memorial

Roll of Honour

S - Z

6397 Private

Horace Claude Sambrook

19th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th April 1918, aged 31.

From Granville, NSW. A labourer prior to enlistment, Pte Sambrook embarked on board HMAT Suevic (A29) on 11 November 1916. He served in Belgium and France and was killed in action at Hangard Wood.

Horace Claude Sambrook

19th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th April 1918, aged 31.

From Granville, NSW. A labourer prior to enlistment, Pte Sambrook embarked on board HMAT Suevic (A29) on 11 November 1916. He served in Belgium and France and was killed in action at Hangard Wood.

3867 Private

Percy Single

47th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th August 1916, aged 29.

Son of Edwin Everett Single and Frances Hannah Single, of Woodford, Queensland. Born at Emmaville, New South Wales.

A blacksmith prior to enlisting on 3 June 1915, Pte Single embarked from Sydney, NSW, aboard HMAT Suffolk on 30 November 1915. He was killed in action at Pozieres, France.

Percy Single

47th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th August 1916, aged 29.

Son of Edwin Everett Single and Frances Hannah Single, of Woodford, Queensland. Born at Emmaville, New South Wales.

A blacksmith prior to enlisting on 3 June 1915, Pte Single embarked from Sydney, NSW, aboard HMAT Suffolk on 30 November 1915. He was killed in action at Pozieres, France.

Lieutenant

Elliott Darcy Slade

33rd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

30th March 1918, aged 23.

Son of John Elliott Slade and Ada Slade, of "Ellerker", Cleveland St., Wahroonga, New South Wales. Born at Dulwich Hill. New South Wales.

An articled clerk and university student in civilian life, 5027 Private Slade enlisted in Hospital Transports Staff (No 1 Hospital Ship HMAT Karoola (A63), Australian Army Medical Corps, on 31 May 1915. The unit embarked from Sydney on HMAT Orsova (A67) on 14 July 1915. He returned to Australia on 4 December 1915 whilst on duty with No 1 Hospital Ship. He then transferred to the 2nd Military District for allotment to a combatant corps. On 30 September 1916 with the rank of 2nd Lt, Slade was appointed to the 33rd Battalion. 2nd Lt Slade embarked with the 7th Reinforcements from Sydney on HMAT Anchises (A68) on 24 January 1917. During 1917, 2nd Lt Slade transferred to the 63 Battalion, was promoted to Lieutenant, and then transferred back to the 33rd Battalion. Lt Slade was in charge of 4 Platoon during operations near Hangard Wood, France, when he was killed in action on 3 March 1918. He was aged 23.

Elliott Darcy Slade

33rd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

30th March 1918, aged 23.

Son of John Elliott Slade and Ada Slade, of "Ellerker", Cleveland St., Wahroonga, New South Wales. Born at Dulwich Hill. New South Wales.

An articled clerk and university student in civilian life, 5027 Private Slade enlisted in Hospital Transports Staff (No 1 Hospital Ship HMAT Karoola (A63), Australian Army Medical Corps, on 31 May 1915. The unit embarked from Sydney on HMAT Orsova (A67) on 14 July 1915. He returned to Australia on 4 December 1915 whilst on duty with No 1 Hospital Ship. He then transferred to the 2nd Military District for allotment to a combatant corps. On 30 September 1916 with the rank of 2nd Lt, Slade was appointed to the 33rd Battalion. 2nd Lt Slade embarked with the 7th Reinforcements from Sydney on HMAT Anchises (A68) on 24 January 1917. During 1917, 2nd Lt Slade transferred to the 63 Battalion, was promoted to Lieutenant, and then transferred back to the 33rd Battalion. Lt Slade was in charge of 4 Platoon during operations near Hangard Wood, France, when he was killed in action on 3 March 1918. He was aged 23.

5477 Private

George Harold Slade

12th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

15th April 1917, aged 17.

Son of John Slade and his wife Alice Jane Tytherleigh, of Koree, Lynch's Creek, New South Wales. Born at Woodenbong, New South Wales.

A farmer prior to enlistment, he embarked with the 17th Reinforcements on SS Hawkes Bay on 20 April 1916. On 15 April 1917 he was killed in action at Lagnicourt, France, aged 17 years and seven months.

George Harold Slade

12th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

15th April 1917, aged 17.

Son of John Slade and his wife Alice Jane Tytherleigh, of Koree, Lynch's Creek, New South Wales. Born at Woodenbong, New South Wales.

A farmer prior to enlistment, he embarked with the 17th Reinforcements on SS Hawkes Bay on 20 April 1916. On 15 April 1917 he was killed in action at Lagnicourt, France, aged 17 years and seven months.

3879 Private

Frederick William Smith

32nd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

18th June 1918, aged 32.

A gardener from Hectorville, South Australia, prior to enlistment, he embarked with the 9th Reinforcements aboard HMAT Commonwealth on 21 September 1916 for Plymouth, England. He proceeded to France in late December 1916 but was hospitalised due to illness and did not join his battalion on the Western Front near Fricourt, France, until early February 1917. After a week in the field he was hospitalised for a further two months due to illness. Pte Smith was detached to the 8th Light Trench Mortar Battery from early October 1917 until late the following December. Pte Smith was killed in action Near Amiens, France, on 18 June 1918.

Frederick William Smith

32nd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

18th June 1918, aged 32.

A gardener from Hectorville, South Australia, prior to enlistment, he embarked with the 9th Reinforcements aboard HMAT Commonwealth on 21 September 1916 for Plymouth, England. He proceeded to France in late December 1916 but was hospitalised due to illness and did not join his battalion on the Western Front near Fricourt, France, until early February 1917. After a week in the field he was hospitalised for a further two months due to illness. Pte Smith was detached to the 8th Light Trench Mortar Battery from early October 1917 until late the following December. Pte Smith was killed in action Near Amiens, France, on 18 June 1918.

5092 Private

Hunter Laurence Smith

30th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

23rd June 1918, aged 19.

A clerk of Wallsend, NSW, he embarked on HMAT Marathon (A74) on 10 May 1917 with the 14th Reinforcements. He was killed in action at Morlancourt, France.

2483 Private T. Wolfe witnessed Hunter Smith's death, he said:

"During raiding operations on the morning of 23rd June 1918, Pte Smith and myself were in the same bombing team. After our advance had been stopped by heavy M. G. fire, Pte Smith and myself took cover in a shell hole and after our retire signal had been given, we tried to make our way back to our own lines. I was about 10 yards in advance of Smith, helping a wounded man along, when suddenly, a Very Light went up from the German line, and I saw Smith rise up and make to run and catch me up. He only went a couple of paces and an M. Gun opened fire on him and he fell. Shortly after, a large German bombing party bombed, and passed over the ground where he fell, and I had no possible hope of recovering his body as I couldn't leave the man I was helping in."

Hunter Laurence Smith

30th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

23rd June 1918, aged 19.

A clerk of Wallsend, NSW, he embarked on HMAT Marathon (A74) on 10 May 1917 with the 14th Reinforcements. He was killed in action at Morlancourt, France.

2483 Private T. Wolfe witnessed Hunter Smith's death, he said:

"During raiding operations on the morning of 23rd June 1918, Pte Smith and myself were in the same bombing team. After our advance had been stopped by heavy M. G. fire, Pte Smith and myself took cover in a shell hole and after our retire signal had been given, we tried to make our way back to our own lines. I was about 10 yards in advance of Smith, helping a wounded man along, when suddenly, a Very Light went up from the German line, and I saw Smith rise up and make to run and catch me up. He only went a couple of paces and an M. Gun opened fire on him and he fell. Shortly after, a large German bombing party bombed, and passed over the ground where he fell, and I had no possible hope of recovering his body as I couldn't leave the man I was helping in."

Lieutenant

John Lyall Smith, M. C.

25th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

29th July 1916, aged 30.

From Ayr, Qld; originally of Aberdeen, Scotland. A mason prior to enlisting on 7 February 1915, John Lyall Smith had served eighteen months with the Gordon Highlanders and four years with the Scottish Horse prior to coming to Australia. Given the rank of Regimental Sergeant Major at enlistment, he embarked with the 25th Battalion, Pioneers, from Brisbane onboard HMAT Aeneas (A60) on 29 June 1915. He arrived for service at Gallipoli on 4 September 1915 and was promoted to the rank of Second Lieutenant (2nd Lt) on 3 November 1915. 2nd Lt Smith arrived in France for service on the Western Front on 19 March 1916 and on 3 June 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for "gallant services" at Gallipoli. He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant (Lt) on 25 July 1916 and was killed in action at Pozieres, France.

John Lyall Smith, M. C.

25th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

29th July 1916, aged 30.

From Ayr, Qld; originally of Aberdeen, Scotland. A mason prior to enlisting on 7 February 1915, John Lyall Smith had served eighteen months with the Gordon Highlanders and four years with the Scottish Horse prior to coming to Australia. Given the rank of Regimental Sergeant Major at enlistment, he embarked with the 25th Battalion, Pioneers, from Brisbane onboard HMAT Aeneas (A60) on 29 June 1915. He arrived for service at Gallipoli on 4 September 1915 and was promoted to the rank of Second Lieutenant (2nd Lt) on 3 November 1915. 2nd Lt Smith arrived in France for service on the Western Front on 19 March 1916 and on 3 June 1916 he was awarded the Military Cross (MC) for "gallant services" at Gallipoli. He was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant (Lt) on 25 July 1916 and was killed in action at Pozieres, France.

4299 Private

Robert Percival Staley

7th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

15th April 1918

A farm labourer of Maryborough, Victoria, he embarked on HMAT Demosthenes on 29 December 1915 with the 13th Reinforcements. A member of a mobile gun crew, he was killed on 15 April 1918, while standing up to shoot from a field post at a crossroad at Nieppe Forest, near Ypres. He was buried at the estaminet (inn) opposite top the field post, but no cross was erected. His grave was lost.

Robert Percival Staley

7th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

15th April 1918

A farm labourer of Maryborough, Victoria, he embarked on HMAT Demosthenes on 29 December 1915 with the 13th Reinforcements. A member of a mobile gun crew, he was killed on 15 April 1918, while standing up to shoot from a field post at a crossroad at Nieppe Forest, near Ypres. He was buried at the estaminet (inn) opposite top the field post, but no cross was erected. His grave was lost.

2169 Private

Ion* Bossley Varnell Tillett

34th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th May 1918, aged 28.

Son of George Bossley Varnell Tillett and Christena Tillett, of Kendall, Camden Haven, New South Wales. Born at Toowoomba, Queensland.

From Kendall, NSW. An engineer before enlisting in April 1916, Pte Tillett left Australia for England with the 3rd Reinforcements in August 1916, and arrived in France for service on the Western Front in November 1916. He was killed during the 34th Battalion's attack on the German positions along the Bray-Corbie Road near Morlancourt

2298, Corporal H. H. Dight of the same battalion witnessed Private Tillett's death:

"B Company was in action on the north side of the Bray-Corbie Road, they hopped over about 10.30pm., and about 20 minutes afterwards, when they had advanced 3 or 400 yards, Tillett was hit in the head by a bomb while they were lying in front of the enemy wire trying to get through it.

I saw Tillett get up holding his head and call out for stretcher bearers. He walked for a few paces and then fell, apparently dead. One of his mates, named George Shearwood, was killed outright by the same bomb. I had to keep going and succeeded in killing with bombs two of the men who had killed Tillett and Shearwood and shot another of the enemy.

The obejective was captured.

I heard that Tillett was buried though never learned the exact place. Tillett was highly thought of by his mates, being of a quiet disposition, we had been in several stunts together and knew each other very well."

George Shearwood's grave was also lost and he is commemorated along with Ion Tillett on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial.

* Note: CWGC show his name as Ian but Australian records show it as Ion.

Ion* Bossley Varnell Tillett

34th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th May 1918, aged 28.

Son of George Bossley Varnell Tillett and Christena Tillett, of Kendall, Camden Haven, New South Wales. Born at Toowoomba, Queensland.

From Kendall, NSW. An engineer before enlisting in April 1916, Pte Tillett left Australia for England with the 3rd Reinforcements in August 1916, and arrived in France for service on the Western Front in November 1916. He was killed during the 34th Battalion's attack on the German positions along the Bray-Corbie Road near Morlancourt

2298, Corporal H. H. Dight of the same battalion witnessed Private Tillett's death:

"B Company was in action on the north side of the Bray-Corbie Road, they hopped over about 10.30pm., and about 20 minutes afterwards, when they had advanced 3 or 400 yards, Tillett was hit in the head by a bomb while they were lying in front of the enemy wire trying to get through it.

I saw Tillett get up holding his head and call out for stretcher bearers. He walked for a few paces and then fell, apparently dead. One of his mates, named George Shearwood, was killed outright by the same bomb. I had to keep going and succeeded in killing with bombs two of the men who had killed Tillett and Shearwood and shot another of the enemy.

The obejective was captured.

I heard that Tillett was buried though never learned the exact place. Tillett was highly thought of by his mates, being of a quiet disposition, we had been in several stunts together and knew each other very well."

George Shearwood's grave was also lost and he is commemorated along with Ion Tillett on the Villers-Bretonneux Memorial.

* Note: CWGC show his name as Ian but Australian records show it as Ion.

5417 Private

Sydney Henry Turpin

26th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

2nd April 1918, aged 26.

Son of Henry and Annie Turpin; husband of Charlotte Turpin, of Nind St., Southport, Oueensland.

A labourer prior to enlisting in February 1916, Pte Turpin embarked from Brisbane with the 14th Reinforcements on board HMAT Itonus (A50) on 8 August 1916.

He was killed in action at Messines, Belgium.

Sydney Henry Turpin

26th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

2nd April 1918, aged 26.

Son of Henry and Annie Turpin; husband of Charlotte Turpin, of Nind St., Southport, Oueensland.

A labourer prior to enlisting in February 1916, Pte Turpin embarked from Brisbane with the 14th Reinforcements on board HMAT Itonus (A50) on 8 August 1916.

He was killed in action at Messines, Belgium.

2094 Private

Claude Ernest Ward

22nd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

Between 27th July and 4th August 1916.

From Point Lonsdale, Vic. Pte Ward enlisted on 26 July 1915 and embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT Anchises on 26 August 1915. He was killed in action on 27 July 1916 in France while serving with the 22nd Battalion.

Claude Ernest Ward

22nd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

Between 27th July and 4th August 1916.

From Point Lonsdale, Vic. Pte Ward enlisted on 26 July 1915 and embarked from Melbourne aboard HMAT Anchises on 26 August 1915. He was killed in action on 27 July 1916 in France while serving with the 22nd Battalion.

Captain

Thomas Kennedy Westbrook

2nd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th May 1917, aged 21.

Son of Thomas Lempriere Westbrook and Margaret Elizabeth Westbrook, of "Lineda", Doncaster Avenue, Kensington, New South Wales. Born at Waverley, New South Wales.

Enlisted as a Second Lieutenant on 27 August 1914, aged 19, and embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT Suffolk on 18 October 1914. In March 1916 he was promoted to the rank of captain. Captain Westbrook was killed in action in France on 7 May 1917.

550 Private, A. R. Shewes witnessed the death of Captain Westbrook:

"I saw him killed at Bullecourt, May 7th 1917, death instantaneous. Hit with fragments of a shell through the neck, I was wounded by the same shell very close to him, and I saw them carry him away to the dressing station a mile off. I cannot say where he was buried."

Thomas Kennedy Westbrook

2nd Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

7th May 1917, aged 21.

Son of Thomas Lempriere Westbrook and Margaret Elizabeth Westbrook, of "Lineda", Doncaster Avenue, Kensington, New South Wales. Born at Waverley, New South Wales.

Enlisted as a Second Lieutenant on 27 August 1914, aged 19, and embarked from Sydney aboard HMAT Suffolk on 18 October 1914. In March 1916 he was promoted to the rank of captain. Captain Westbrook was killed in action in France on 7 May 1917.

550 Private, A. R. Shewes witnessed the death of Captain Westbrook:

"I saw him killed at Bullecourt, May 7th 1917, death instantaneous. Hit with fragments of a shell through the neck, I was wounded by the same shell very close to him, and I saw them carry him away to the dressing station a mile off. I cannot say where he was buried."

Second Lieutenant

Lindsay Claude Wickham, M. M.

10th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

25th July 1916, aged 21.

Son of Benjamin and Alice Wickham. Born in South Australia.

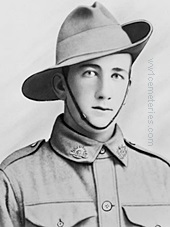

The image shows him when he was 447 Lance Corporal Wickham. A carpenter prior to enlistment, he embarked with B Company from Adelaide aboard HMAT Ascanius on 20 October 1914. The 10th Battalion was among the covering force for the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. L Cpl Wickham suffered several bouts of illness during the Gallipoli campaign and was invalided to Egypt in November 1915. Moving with his unit to France in April 1916, he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant the following month. On 25 July 1916 Sgt Wickham's unit took part in an attack at Pozieres. He was recommended for the award of a Military Medal for leading a party along the parapet and throwing bombs into a German trench, continuing until it was taken despite suffering a leg injury. After his leg was dressed, Sgt Wickham assisted in carrying a badly wounded man, named Fred Brown who died on the way, to the aid post, carrying him for part of the way on his back. Shortly after the battle he was reported wounded and missing in action.

Lindsay Claude Wickham, M. M.

10th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

25th July 1916, aged 21.

Son of Benjamin and Alice Wickham. Born in South Australia.

The image shows him when he was 447 Lance Corporal Wickham. A carpenter prior to enlistment, he embarked with B Company from Adelaide aboard HMAT Ascanius on 20 October 1914. The 10th Battalion was among the covering force for the ANZAC landing at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915. L Cpl Wickham suffered several bouts of illness during the Gallipoli campaign and was invalided to Egypt in November 1915. Moving with his unit to France in April 1916, he was promoted to the rank of Sergeant the following month. On 25 July 1916 Sgt Wickham's unit took part in an attack at Pozieres. He was recommended for the award of a Military Medal for leading a party along the parapet and throwing bombs into a German trench, continuing until it was taken despite suffering a leg injury. After his leg was dressed, Sgt Wickham assisted in carrying a badly wounded man, named Fred Brown who died on the way, to the aid post, carrying him for part of the way on his back. Shortly after the battle he was reported wounded and missing in action.

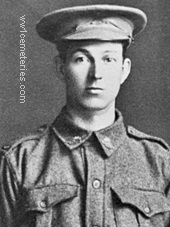

545 Corporal

Gilbert Glenloth Wilson

2nd Pioneers, Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

14th November 1916, aged 24.

Son of Frederick Wilson, of Iob, Princes St., Port Melbourne and the late Eleanor Wilson. Bom at Sale Victoria.

An engine cleaner for the Victorian Railways prior to enlistment, Pte Wilson embarked on board HMAT Ulysses (A38) on 10 May 1915. He served at Gallipoli from August 1915 until December 1915. Pte Wilson was transferred to the 2nd Pioneer Battalion and arrived in France in March 1916 being appointed Lance Corporal and then Acting Corporal in August 1916. Corporal Wilson was killed in action at Flers, France on 14 November 1916. He was 24 years of age. Corporal Wilson's brother Lieutenant Frederick Gladstone Wilson, aged 19, was killed in action at Gallipoli on 26 April 1915 and buried at Courtney's and Steel's Post Cemetery.

Gilbert Glenloth Wilson

2nd Pioneers, Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

14th November 1916, aged 24.

Son of Frederick Wilson, of Iob, Princes St., Port Melbourne and the late Eleanor Wilson. Bom at Sale Victoria.

An engine cleaner for the Victorian Railways prior to enlistment, Pte Wilson embarked on board HMAT Ulysses (A38) on 10 May 1915. He served at Gallipoli from August 1915 until December 1915. Pte Wilson was transferred to the 2nd Pioneer Battalion and arrived in France in March 1916 being appointed Lance Corporal and then Acting Corporal in August 1916. Corporal Wilson was killed in action at Flers, France on 14 November 1916. He was 24 years of age. Corporal Wilson's brother Lieutenant Frederick Gladstone Wilson, aged 19, was killed in action at Gallipoli on 26 April 1915 and buried at Courtney's and Steel's Post Cemetery.

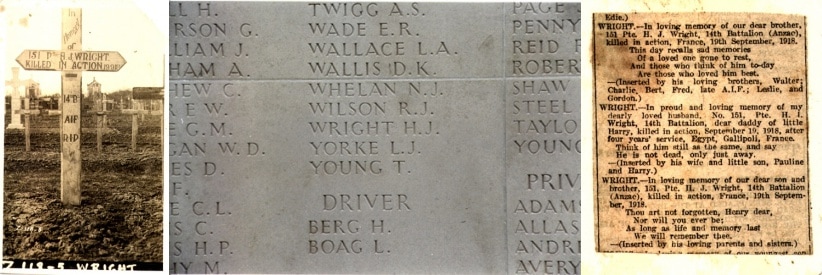

151 Private

Henry James Wright

14th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

19th September 1918, aged 30.

Son of Edward and Marion Emma Wright; husband of Pauline Wright, of 6, Winifred St., Essendon, Victoria.

Henry James Wright

14th Bn. Australian Infantry, A. I. F.

19th September 1918, aged 30.

Son of Edward and Marion Emma Wright; husband of Pauline Wright, of 6, Winifred St., Essendon, Victoria.

IT’S MY DUTY TO GO

(All pictures and text by Ken Wright)

I never met my uncle Henry but I wish I had. It was only through my interest in a few surviving letters and postcards from the Great War that I have managed to trace some of his life. It was a period when writing a letter was something done with style. To get to know Henry the journey begins with the news of war with Germany was declared on 4 August 1914. Patriotic fever spread through out Australia and Henry Wright’s decision was final. No matter what his new wife Pauline said, or his parents, or any of his six brothers and two sisters. He was going to enlist. War had been declared and the Australian Imperial Forces needed men to fight. Besides he argued, it was his duty to go. Henry left of the family home at no 6 Winifred Street, North Essendon a Melbourne suburb [Victoria-Australia] for the spartan army barracks at Broadmeadows and became Private H. J. Wright, regimental number 151, A Company, 14th Battalion on 1st October 1914. He was only 26. After fifteen weeks basic training, Private Wright sailed from Port Melbourne aboard the troopship A38 [Ulysses] bound for the Middle East. Henry became a prolific letter writer, but most of the letters have now been lost over time. The following article is from the surviving postcards and letters and has been shortened to present the family closeness, emotions, sentence structure and use of words of the time. The reader might also note that the war is seen as an adventure in the first letters and slowly changes to the realisation that war is nothing more than misery and death.

Henry went ashore at Gallipoli at 10-30am on 26 April 1915 and describes his experience in a letter to a brother on June 27.

Dear Les, Just a few lines in answer to your welcome letter received here 23rd June and dated May 14th. Well Les, I am pleased to hear you are well and like your place. I had a letter from Mother saying Bert and Fred had sailed but did not know what place they were going to. I thought that we still had a few brothers left who would enlist. I suppose you would have had a try had you been old enough. Well Les, I have up to now managed to dodge the bullets which fall pretty thick at times. We are giving the Turks all the fight they want. They are very frightened of the bayonet. They squeal like blue hell when they get a touch. We live in dugouts cut in the side of the hill just like rabbits. They are pretty safe from bullets and shrapnel. We do our own cooking and are getting experts at it. Now Les, I will close hoping you are well and will always be pleased to hear from you,-------------- ---I remain your loving brother, Henry.

Unfortunately Henry was wounded by shrapnel in an attack on Hill 60 on 21 August and sent to England onboard a hospital ship and unaware of his younger brothers, Fred and Albert, members of the 21st Battalion had landed on Gallipoli on 7th September 1915. Fred was later sent home and discharged as medically unfit with Enteric fever in 1916, and Albert went on to fight in France and Flanders but he was also sent home and discharged with trench feet in 1917.

Henry went ashore at Gallipoli at 10-30am on 26 April 1915 and describes his experience in a letter to a brother on June 27.

Dear Les, Just a few lines in answer to your welcome letter received here 23rd June and dated May 14th. Well Les, I am pleased to hear you are well and like your place. I had a letter from Mother saying Bert and Fred had sailed but did not know what place they were going to. I thought that we still had a few brothers left who would enlist. I suppose you would have had a try had you been old enough. Well Les, I have up to now managed to dodge the bullets which fall pretty thick at times. We are giving the Turks all the fight they want. They are very frightened of the bayonet. They squeal like blue hell when they get a touch. We live in dugouts cut in the side of the hill just like rabbits. They are pretty safe from bullets and shrapnel. We do our own cooking and are getting experts at it. Now Les, I will close hoping you are well and will always be pleased to hear from you,-------------- ---I remain your loving brother, Henry.

Unfortunately Henry was wounded by shrapnel in an attack on Hill 60 on 21 August and sent to England onboard a hospital ship and unaware of his younger brothers, Fred and Albert, members of the 21st Battalion had landed on Gallipoli on 7th September 1915. Fred was later sent home and discharged as medically unfit with Enteric fever in 1916, and Albert went on to fight in France and Flanders but he was also sent home and discharged with trench feet in 1917.

Henry's brothers Fred, Albert & Charles

From hospital, Henry wrote two letters describing how Australians were treated in England.

My Dear Mother,

You no doubt are very anxious about me, for I suppose you would get a telegram to say that I was wounded and you are wondering how badly. I am pleased to say my wounds are not serious, and also that I am a lucky man to be sitting up in bed in dear old England. I am in the Hampstead (New End) Military Hospital where we are looked after splendidly. When the boys are able to walk, they are allowed out from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. They are often taken for motor trips all over London. The people are very kind, and invite the boys to afternoon tea. The Old Bull and Bush Inn is only ten minutes walk from here. Little did I think I would one day see the original? I will write to you again about the different places when I can get about. Don’t worry about me, my wounds are not serious. I expect to be about in a couple of weeks. I have an appetite like a horse [I should think so after bully beef and biscuits for four months]

My dear Mother, Father, Brothers and Sisters,

I am getting along splendidly, and can get about with the aid of a stick. I have had a great week for outings. SUNDAY,--Motor drive to the country and saw the great flying grounds at Hendon; then afternoon tea at a lovely house at Highgate [ photo taken on the lawn] ; entertained with music; plenty of cigars and cigarettes.

MONDAY – A motor drive to the country, 30 miles of lovely scenery; afternoon tea on the lawn.

TUESDAY—20 of us were entertained at the Hampstead Golf Club. We had a competition game and I reckon I am hot stuff at golf. We were treated very well—plenty of cigarettes and our tea was good. I thought I would never be able to get up from the table. The ladies sang songs to us. Of course I made eyes at one of the young ladies and we got quite chatty and I was sorry we had to go. I am looking forward to the next invitation to play golf.

WEDNESDAY--- Three of us motored out to Watford and had afternoon tea at the big house.

SATURDAY---A lady took five of us in a motor to Richmond, about 18 miles from here. We had a glorious time. We passed Lord’s Cricket ground, over Hammersmith Bridge, through the great Richmond Park, covered with forests of oak, chestnut and silver birch trees and saw hundreds of deer. We had afternoon tea on the banks of the Thames, came back through Bush Park. We were shown Hampton Court Palace, the favourite residence of Queen Victoria. We crossed over Kingston Bridge and had a real good time. The people here are very good to Australians and cannot do enough for us. If we go for a walk in the afternoon we are stopped by the women and children and given cigarettes and sweets and asked to come for tea. We have concerts two or three times a week, some of the best singers and artists from theatres entertaining us. The weather here is getting cold, so we are to have more concerts and moving pictures. Corporal Stuckey is here with me. He was wounded the same day as myself. You remember he and Trevillian came to tea one Sunday night before we left Broadmeadows. Tomorrow, Stuckey, two other Australians and myself are invited for a motor ride to the principal parts of London. So tomorrow I will have some news to tell you of our trip.

TUESDAY---I do not know how to tell you what a splendid outing we had today. I will do my best to explain it. We left here at 2pm and were soon in the crowded but wonderful city of London. We crossed Blackfriars Bridge over the Thames, did Regent Street, Leicester Square [ high monument of Ajax defying the lightning ] Trafalgar Square, with the splendid monument of Nelson and the Duke of Wellington. We motored around the historical building, the Tower of London, which dates back hundreds of years. I cannot write how these wonderful buildings impress one at first sight. When I get my furlough I am going to look over this building and I will write you more news of it. We passed over Tower Bridge---a tremendous big bridge. A roadway is lifted up by hydraulic power to let the steamers pass. We then recrossed the Thames over Westminister Bridge, saw the bronze statue of Boadicea, and the wonderful obelisk of Cleopatra. This huge stone was brought from Egypt in Queen Victoria’s time, and was cut out of solid granite about the time the Pyramids were built. We saw the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, Scotland Yard, Westminster Abbey, Albert Memorial, St Paul’s Cathedral, Buckingham Palace, the wonderful Queen Victoria Memorial, Hyde Park, Rotten Row and dozens of other places of interest. I have not written of the splendour and wonder of it all but when I get out on furlough, I mean to spend most of the time inside these old historical places and will be able to describe them better to you.

Well, my dear Mother and Father, I know you must be having a most anxious time, wondering how we are all getting on and dread each day to hear bad news; but the danger is not so great as you imagine, and if you could see us at our work in the trenches and under fire, and how lightly we take it all, I am sure you would not worry so much. I [and my brothers, I am sure] are always thinking of you at home. I can see you now, dear Mother, sitting down doing crochet work and Dad on the sofa reading the paper. How lonely the old house must seem; but cheer up, we will some day all return again. We are doing work for our country that you must be proud of. You have given four sons and this is a very big thing out of our family. I will send you postcards of London and the principal buildings when I get out. I cannot draw any money while in hospital. I do not mind being here for we are treated like toffs.

While Henry was recovering from his wounds, enjoying English hospitality and afternoon tea on the lawns, motor drives in the country, his Battalion was withdrawn from Gallipoli on 18 December 1915 and sent to France. Henry returned to active service in April 1916. Brother Charles arrived in France and was in action in the same area. In those days, getting shot was an occupational hazard and the Wright brothers were attracting their fair share of lead. Henry was wounded again, this time in the right arm, left leg and suffers from shell-shock in or near Pozieres on 2 July 1916 and sent to the Northumberland War Hospital in England to recover. Not to be out done by his brother, Charlie is shot in the right leg in an attack on Mouquet Farm also near Pozieres. He took seven months to recover only to be shot again in April 1917; this time it was the right arm, head and back. The Army decided to send him back home as medically unfit in August 1918.

Henry remained in England as his wounds were taking a long time to heal. He was eventually fit enough to be transferred from hospital to the School of Musketry in Tidworth on 2 February, 1917, where he was given light cleaning duties. It was from here Henry wrote on 6 October about his most inner most thoughts about the war, the nostalgia for his home and about his life in general.

Dear Les and Gordon,

I think it is about time I wrote you a few lines for no doubt you want to know a little news of this side of the world. It always appeals to anyone who has not travelled that they would like to see different parts of the world, but take my dinkum tip and stick to the dear old home for there is absolutely no place like it. Mind you, I am not sorry I came away because to hang back would be like a coward’s game, but to leave home just to roam about is a very foolish idea. I know when I was your age I was always wanting to roam the world. I know perfectly well now that ones home sweet home is paradise. I have been hungry many a time and scores of times been without a smoke. Just sitting down to Bully beef and biscuits for three meals a day of course next day you would get a change to biscuits and Bully beef.

Well dear Brothers, I will begin my explanation of the countries I have visited with Egypt. Now Egypt is a pretty but dirty place. The natives are a very stinking lot of devils and if you do not watch them, they will put a knife between your ribs. They are very treacherous and the only way to treat them is to make them frightened of you. When we first went to Egypt, we could get things very cheap, but when they found out the Australians had plenty of money, everything went up double the price. We could buy 2 big oranges for a half penny, 6 eggs, twopence or a good feed for sixpence. The native women do all the work. It is a very common sight to see them carrying heavy loads on their head and a baby on their back. Of course these are the Arabs and they are black. The Egyptians are as white skinned as us and are very fine race of people. As you know by the history books, Egypt is a very old place and has some very old interesting sites. The Pyramids are a wonderful sight and the Tombs which date back thousands of years ago. I think every Australian who went to Egypt took the opportunity of seeing these wonderful old places. We were camped at Heliopolis about 10 miles from Cairo and close to our camp was a very old burying ground and often our boys would go over and dig up the remains and find beads, coins and other curios. I have seen some of the boys come home with a skull and put a lighted candle inside of it at night time. You can guess it would give the boys who came home late a big scare especially if they were a bit tipsy. Heliopolis camp was only a desert when we first landed there but all sorts of shops went up like lightning and many a nigger made a fortune in no time. Our boys spent thousands and thousands of pounds in Egypt. Australians are the best paid soldiers in the world and they deserve it for they are bonza fighters.

Well dear brothers, we did not have the luck to take Constantinople. I cannot tell you much of the Turkish cities but I saw plenty of Turks at Gallipoli. I can say they are a fine body of men and dash good fighters. My rememberances of the four months on the Peninsula are like a big nightmare. I had a charmed life there and don’t know how I escaped being blown to pieces many a time. I could fill a book of narrow escapes. Now we will pass on to the land of frogs and snails. By joves it seemed a lovely country after Egypt and Gallipoli. Everywhere you see lovely fields of grape vines, fruit trees, cultivated land and rivers. The people are a splendid race and women work in the fields like a man. It is a common sight to see them ploughing and hoeing in the fields and we Australians were always greeted the time of day. We often bought bread off them instead of eating biscuits. Our three days trip from Marseilles to a place called Baielui was through the prettiest country I ever saw. We were within 8 miles of Paris and could see the Eiffel Tower plainly. It was a certainty that if they took us through Paris, we would have taken leave and had a look around Paris. We were only a little over a week at Baielui about 10 miles from the trenches. We could plainly hear the booming of the heavy guns.

Well brothers, everyone who goes to the front has narrow escapes and I have had mine. One day in the trenches, previous to doing this raid, Frank Trevillian and I were just killing time and having a sing-song and old Fritz was shelling our part of the trench with a 9 point 5 shell (known amongst the soldiers as coal boxes). Now one of these coal boxes landed two yards in front of the trenches where Frank and I was, and by a piece of luck, missed fire. Had it gone off, we should have been in little pieces? Frank and I looked at one another and then went on singing, but I can tell you, it made us think of better places than that dammed old trench. By Joves, as I sit here and write these lines to you boys, I am indeed thankful I am having a spell from it all and sincerely hope I have no more fighting for a while. I am not afraid to go back, but I think it only right that we old hands should have a spell. I have now six scars from bullets to show, so think that quite sufficient. I had word from Charlie lately saying he was being discharged from hospital, so I am in hopes of seeing him soon. Poor old Bert will miss Charlie very much. I do hope he gets through alright. Fred is very lucky getting his discharge and I am very glad for it will help to cheer up Mother and Dad. I’ll bet you boys are proud of your soldier brothers and you have the satisfaction of saying that none of them were slackers.

Well dear brothers, war is nothing else but pure murder and the sooner it is all over the better for everyone concerned. I am looking forward to the time when it is all over and we can come home again. I guess we will have a good old time. I am positive that at Dad’s spree the champagne will get a severe hiding. I have contracted a terrible thirst since joining the Army. Of course I put it down to Bully Beef.

Well dear brothers, we have some characters in the Australian Army. All kinds from bank clerks to bush whackers. Wherever there is a mix up with fists, some of our boys are in it, but a softer hearted lot you could not find in the whole world. They are ever willing to help a man wounded, or anyone down on his luck. They have taught many an Englishman manners by getting up and giving a lady their seat. They are rough and ready but no matter what country they go to, they are classed as gentlemen. In Hospital over here we are treated with great respect and want for nothing. We get scores of invitations to visit the wealthy peoples’ houses. I have had many an outing and hope for many more similar ones. I have a nice light job now looking after these rooms in a musketry school. I have only to keep them tidy, and can finish them in two hours. The job may last six weeks or six months. I hope it hangs out until the end of the war. Three good meals a day and a nice warm bed to lie on so I can’t growl. Now Leslie and Gordon, I want you to write me a letter and let me know how you are getting on, what kind of work you are doing and if you want to know any particular news about different countries I have been in. Just mention it in your letter and I will be only too pleased to give you any information I can. I will now close, hoping this finds you both well,

I remain your aff brother Henry.

On 16 April 1918 Henry wrote to his mother and his emotional yearning for home and family shows in the letter.

My Dear Mother,

Just a few lines to say I am well and still going strong at the Musketry School. All those rumours of having to go to France again have now died down and we are going on as usual. I am very thankful for I should not like going over there again. I have had all the fighting I want for all time.

Well dear Mother, I was very pleased to receive 6 letters today from Australia, three from you, two from Pauline and one from Charlie and you can guess how pleased I was to hear Charlie had returned home safely. I only wished I could see you all seated down in the old home, so happy and contented all would be.

Well cheerio dear Mother, my time is coming along by next Xmas and don’t forget to keep that Hogshead of beer on ice. Joves, I get thirsty every time I think of it. I guess I can do justice to my share of it. I do not mention Champayne now as I reckon the Australians have drank all that in France. You can bet I had my share when I was there. By Joves, young Gordon is a brick and is sticking to that job in N.S.W. I reckon it will be the making of him. I sincerely hope he sticks to banking his money as he is doing for it is the finest thing for a young fellow to have a few pounds behind him. I really had no idea work was at such a standstill in Australia. Is Leslie a carpenter? For some months back you mentioned that he was working for Mr Musgrove. So Fred is once again Postman. Does he think it better than soldiering? I wish I had half his luck. I suppose Bert is a gentleman, gets out of bed at 6 every morning [I mean 10 ] By Joves, I laughed at Gordon’s letter that you enclosed. He said his boss had been to America, South Sea Islands and Christ knows where [I wonder where that place is] I am very pleased to know Miss Addey writes to you. Every letter I get from her you are mentioned and I have always an invitation to call and see them whenever I can get leave. Charlie will be able to tell you what a lovely home they have and how splendid they treated him and myself. It is indeed a home away from home. I hope Charlie will not forget to write a few lines to her. I was surprised to hear Bob Bruce is in hospital. Still, he is indeed having a bad time of it. Remember me to him when you write.

Well Mum, I will soon be out of the twenties, only a few days to go now and I will be 30 years of age and reckon it quite time I was home and looking after my little son and heir and I am sure he will want a little sister to play with. I am thinking he will soon be following his old dad over here if this war lasts much longer. What a grand time it will be when it is all over and we get back again to dear old Aussie .You cannot imagine how the dear old place appeals to us after being years away. Well dear Mother, I still do the washing here for the Sargeants and it always brings me in a few extra bob. Everything is so very dear over here. Just now, cigarettes are five and a halfpence a packet of 10 and tobacco is nine and a halfpence an ounce. I was very lucky in receiving a lb of Havelock tobacco from Pauline a couple of weeks ago. It is 2/6 a two ounce tin over here. The civil population are having a terrible hard time of it and I do not know how they manage to live, the prices of food stuffs is awful. Thanks very much for papers and paper cuttings. Everything like that is all news to me. So Florrie [Henry’s sister] has another daughter. By Joves, those two mean business and I don’t think it fair, for I have no chance of keeping pace with them. I reckon I will have to knock them out two at a time. Well now my dear Mother, I must close my letter for this time as I will be soon running out of ink or you will be charged extra postage so with fondest love to all and cheerio till Xmas next,

I remain your ever loving son, Henry.

Henry was quite comfortable in the School of Musketry and naturally in no hurry to return to active service but he failed to obey an order given by an N.C.O and was fined 7 days pay on 24 April 1918 and ordered back to active service.

Overseas Training Battalion, Longbridge, Deverill, Near Warminister, Wiltshire, England. 12 July, 1918.

My dear Father,

Just a few lines to say I am well and will in four days time, be going back to France to fight this Hun. I am now in splendid health and can almost tip the scale at 13 stone. I am just about jumping out of my skin with good training we get and do not mind in the least having to go back. It is for you dear people at home that I am thinking. You will worry, but you must buck up for I may be back again in England before this reaches you.

Well Dad, she is some war and is hanging out a long time, years longer than any of us thought, but there is no doubt that America’s millions of men is going to bring us a victory within a few months. Well Dad, I was in hopes of having Christmas back home with you all but will have to again postpone it. Still I guess that Hogshead beer will keep for another year. We must not forget a goodnight then. I guess you were pleased to have Fred, Bert and Charlie home again and don’t forget Dad, I will soon be back, my good luck will always stick. So Dad, I want you all to cheer up, I am going over to the big stouch with a good heart and I want you to keep the home fires burning and don’t let anything happen to that beer.

Your loving son, Henry.

No 1 Command Depot, Sutton Veny, Wiltshire, England.

Dear Leslie,

I have just received a letter from Mother dated 18th April and you were at that time wanting Dad’s and Mother’s consent to join up. Well dear Brother, I certainly admire your pluck for wanting to do your bit, but if this reaches you before you have taken that step, I would like to point out a few of the disadvantages of this rotten life. First of all, you will miss all those comforts you are use to at home and this is more than you can ever dream of. You will be allowed to draw 2 shillings per day [only] and this at the present time is equal to 6 pence in peace time. I am drawing 1 shilling and I cannot keep my self in smokes. You will find the tucker is much harder to take than you are used to at home. I wish I could sit down to a good square meal like Mother can cook but I am on Army rations and I have not any spare shillings to buy any extra. I have to just want. Here is our day’s menu,

Breakfast;1 slice of dark bread with dripping, a small quantity of a greasy looking mess called Curry and Rice, half pint tea minus sugar.

Dinner; Stew, 1 slice bread, rice pudding or sago.

Tea; 1 slice of bread, jam, margarine, half pint tea.

I don’t know if you ever tasted margarine, I hope not.

Now you are bossed and bullied about by Corporals, Sgnts, Officers and LanceJacks from morning till night and you have to do all kinds of unpleasant duties. You cannot refuse unless you like to lose a few days pay and do a few days clink.

Now Les, Just consider yourself well off where you are and try and use your common sense a little. Surely you must admit Mother and Dad have had enough worry over Fred, Bert, Charlie and myself. I am going to France in a couple of week’s time. I will represent you there and as a last wish, I want you to hang on where you are. You can never realise the misery of it all until you have seen some of it. Hoping dear Brother, this finds you well and that you think before enlisting,

Your loving Brother, Henry.

Henry finally returned to his Battalion on 24 July and wrote home again from somewhere in France on 7 August.

My dear Mother, Father, Sisters and Brothers,

I am going into a big fight to-night and would just like write a few lines for one never knows what may happen. I cannot tell you where we are making our drive but you will read of it in the papers. Well dear parents, brothers and sisters, should I go under you will know I have done my duty and have always tried to play the game. I do indeed feel very thankful that Charlie, Bert, and Fred are back home with you. I am going into that great fight with a good heart and with loving thoughts of you all, my ever fondest love to all,

I remain your ever loving son, Henry.

In a following letter on 20 August he wrote to his parents from the Western Front recording his recent battles and his nostalgia for home as he had not been back to Australia for 40 months.

My dear mother,

We just come out from the front line and our Division was supposed to be out for a couple of weeks spell but everything is so indefinite we may have to go in again in a few days time. Well dear Mother, I was very pleased to receive your letter of 23rd June and know you are alright but you must not worry so much about me. I will come through alright and will admit it is a touch different to my job at Tidworth but still don’t mind and guess it is my fate to see it through and dear Mother, I am ever so grateful it has fallen to myself as the eldest of our four boys to carry on. It does indeed make it easier for me to know my younger brothers are safe home. I am applying for my furlough to Australia but of course will probably have to wait my turn. Pauline says in her letter that she is also trying to get me home so between us we may soon have satisfaction. I think I should just about go out of my head at the thought of coming back to Aussie again. We are always hearing news of the 1914 men being relieved from the line but it seems to stop at that. Anyway, I mean to try hard for it.

Well dear Mother, I am pleased to know Charlie is going through the operation to his arm and do hope it will be a success. I am also pleased to know Bert, Fred and Leslie are working and hope Leslie has changed his mind about joining up and hope Dad is all right again. I reckon Dad ought to have a spell for good, he has done his share. Still dear Mother, I know Dad would not be satisfied with nothing to do. I still have that snap that Fred took of Dad in the garden and like it very much. It brings back memories of that day Charlie and I were told to weed the peas but we went off bird nesting. When we came home for tea, we had to set to and do the weeding anyway. Well, they were good old times and we boys had as good a home as anyone could have wished for. I received a letter from Charlie, Les and Fred by the same mail as yours but I will owe them a letter as we are limited in sending letters and I want to make certain of one for you and Pauline every week.

Well dear Mother, I have made a lot of friends since coming back to the trenches but I cannot say they are nice ones. They are grey in colour and have legs on both sides. Some say Keating’s powder is good but I think a change in flannels much better. People say ‘chats’[lice] will not live on a person in poor health. I must be in tiptop health. Well now dear Mother, I draw my letter to a close hoping this finds you all in the best of health and fondest love to all.

I remain your loving son Henry.

This was Henry’s last letter. He was killed by shellfire around 4pm on 19 September in the Ascension Wood area south west of Bellicourt. His family was notified of his death by the Reverend, Mr Madsen of Richardson Street, Essendon.

My Dear Mother,

You no doubt are very anxious about me, for I suppose you would get a telegram to say that I was wounded and you are wondering how badly. I am pleased to say my wounds are not serious, and also that I am a lucky man to be sitting up in bed in dear old England. I am in the Hampstead (New End) Military Hospital where we are looked after splendidly. When the boys are able to walk, they are allowed out from 2 p.m. to 6 p.m. They are often taken for motor trips all over London. The people are very kind, and invite the boys to afternoon tea. The Old Bull and Bush Inn is only ten minutes walk from here. Little did I think I would one day see the original? I will write to you again about the different places when I can get about. Don’t worry about me, my wounds are not serious. I expect to be about in a couple of weeks. I have an appetite like a horse [I should think so after bully beef and biscuits for four months]

My dear Mother, Father, Brothers and Sisters,

I am getting along splendidly, and can get about with the aid of a stick. I have had a great week for outings. SUNDAY,--Motor drive to the country and saw the great flying grounds at Hendon; then afternoon tea at a lovely house at Highgate [ photo taken on the lawn] ; entertained with music; plenty of cigars and cigarettes.

MONDAY – A motor drive to the country, 30 miles of lovely scenery; afternoon tea on the lawn.

TUESDAY—20 of us were entertained at the Hampstead Golf Club. We had a competition game and I reckon I am hot stuff at golf. We were treated very well—plenty of cigarettes and our tea was good. I thought I would never be able to get up from the table. The ladies sang songs to us. Of course I made eyes at one of the young ladies and we got quite chatty and I was sorry we had to go. I am looking forward to the next invitation to play golf.

WEDNESDAY--- Three of us motored out to Watford and had afternoon tea at the big house.

SATURDAY---A lady took five of us in a motor to Richmond, about 18 miles from here. We had a glorious time. We passed Lord’s Cricket ground, over Hammersmith Bridge, through the great Richmond Park, covered with forests of oak, chestnut and silver birch trees and saw hundreds of deer. We had afternoon tea on the banks of the Thames, came back through Bush Park. We were shown Hampton Court Palace, the favourite residence of Queen Victoria. We crossed over Kingston Bridge and had a real good time. The people here are very good to Australians and cannot do enough for us. If we go for a walk in the afternoon we are stopped by the women and children and given cigarettes and sweets and asked to come for tea. We have concerts two or three times a week, some of the best singers and artists from theatres entertaining us. The weather here is getting cold, so we are to have more concerts and moving pictures. Corporal Stuckey is here with me. He was wounded the same day as myself. You remember he and Trevillian came to tea one Sunday night before we left Broadmeadows. Tomorrow, Stuckey, two other Australians and myself are invited for a motor ride to the principal parts of London. So tomorrow I will have some news to tell you of our trip.

TUESDAY---I do not know how to tell you what a splendid outing we had today. I will do my best to explain it. We left here at 2pm and were soon in the crowded but wonderful city of London. We crossed Blackfriars Bridge over the Thames, did Regent Street, Leicester Square [ high monument of Ajax defying the lightning ] Trafalgar Square, with the splendid monument of Nelson and the Duke of Wellington. We motored around the historical building, the Tower of London, which dates back hundreds of years. I cannot write how these wonderful buildings impress one at first sight. When I get my furlough I am going to look over this building and I will write you more news of it. We passed over Tower Bridge---a tremendous big bridge. A roadway is lifted up by hydraulic power to let the steamers pass. We then recrossed the Thames over Westminister Bridge, saw the bronze statue of Boadicea, and the wonderful obelisk of Cleopatra. This huge stone was brought from Egypt in Queen Victoria’s time, and was cut out of solid granite about the time the Pyramids were built. We saw the Houses of Parliament and Big Ben, Scotland Yard, Westminster Abbey, Albert Memorial, St Paul’s Cathedral, Buckingham Palace, the wonderful Queen Victoria Memorial, Hyde Park, Rotten Row and dozens of other places of interest. I have not written of the splendour and wonder of it all but when I get out on furlough, I mean to spend most of the time inside these old historical places and will be able to describe them better to you.

Well, my dear Mother and Father, I know you must be having a most anxious time, wondering how we are all getting on and dread each day to hear bad news; but the danger is not so great as you imagine, and if you could see us at our work in the trenches and under fire, and how lightly we take it all, I am sure you would not worry so much. I [and my brothers, I am sure] are always thinking of you at home. I can see you now, dear Mother, sitting down doing crochet work and Dad on the sofa reading the paper. How lonely the old house must seem; but cheer up, we will some day all return again. We are doing work for our country that you must be proud of. You have given four sons and this is a very big thing out of our family. I will send you postcards of London and the principal buildings when I get out. I cannot draw any money while in hospital. I do not mind being here for we are treated like toffs.

While Henry was recovering from his wounds, enjoying English hospitality and afternoon tea on the lawns, motor drives in the country, his Battalion was withdrawn from Gallipoli on 18 December 1915 and sent to France. Henry returned to active service in April 1916. Brother Charles arrived in France and was in action in the same area. In those days, getting shot was an occupational hazard and the Wright brothers were attracting their fair share of lead. Henry was wounded again, this time in the right arm, left leg and suffers from shell-shock in or near Pozieres on 2 July 1916 and sent to the Northumberland War Hospital in England to recover. Not to be out done by his brother, Charlie is shot in the right leg in an attack on Mouquet Farm also near Pozieres. He took seven months to recover only to be shot again in April 1917; this time it was the right arm, head and back. The Army decided to send him back home as medically unfit in August 1918.

Henry remained in England as his wounds were taking a long time to heal. He was eventually fit enough to be transferred from hospital to the School of Musketry in Tidworth on 2 February, 1917, where he was given light cleaning duties. It was from here Henry wrote on 6 October about his most inner most thoughts about the war, the nostalgia for his home and about his life in general.

Dear Les and Gordon,

I think it is about time I wrote you a few lines for no doubt you want to know a little news of this side of the world. It always appeals to anyone who has not travelled that they would like to see different parts of the world, but take my dinkum tip and stick to the dear old home for there is absolutely no place like it. Mind you, I am not sorry I came away because to hang back would be like a coward’s game, but to leave home just to roam about is a very foolish idea. I know when I was your age I was always wanting to roam the world. I know perfectly well now that ones home sweet home is paradise. I have been hungry many a time and scores of times been without a smoke. Just sitting down to Bully beef and biscuits for three meals a day of course next day you would get a change to biscuits and Bully beef.

Well dear Brothers, I will begin my explanation of the countries I have visited with Egypt. Now Egypt is a pretty but dirty place. The natives are a very stinking lot of devils and if you do not watch them, they will put a knife between your ribs. They are very treacherous and the only way to treat them is to make them frightened of you. When we first went to Egypt, we could get things very cheap, but when they found out the Australians had plenty of money, everything went up double the price. We could buy 2 big oranges for a half penny, 6 eggs, twopence or a good feed for sixpence. The native women do all the work. It is a very common sight to see them carrying heavy loads on their head and a baby on their back. Of course these are the Arabs and they are black. The Egyptians are as white skinned as us and are very fine race of people. As you know by the history books, Egypt is a very old place and has some very old interesting sites. The Pyramids are a wonderful sight and the Tombs which date back thousands of years ago. I think every Australian who went to Egypt took the opportunity of seeing these wonderful old places. We were camped at Heliopolis about 10 miles from Cairo and close to our camp was a very old burying ground and often our boys would go over and dig up the remains and find beads, coins and other curios. I have seen some of the boys come home with a skull and put a lighted candle inside of it at night time. You can guess it would give the boys who came home late a big scare especially if they were a bit tipsy. Heliopolis camp was only a desert when we first landed there but all sorts of shops went up like lightning and many a nigger made a fortune in no time. Our boys spent thousands and thousands of pounds in Egypt. Australians are the best paid soldiers in the world and they deserve it for they are bonza fighters.

Well dear brothers, we did not have the luck to take Constantinople. I cannot tell you much of the Turkish cities but I saw plenty of Turks at Gallipoli. I can say they are a fine body of men and dash good fighters. My rememberances of the four months on the Peninsula are like a big nightmare. I had a charmed life there and don’t know how I escaped being blown to pieces many a time. I could fill a book of narrow escapes. Now we will pass on to the land of frogs and snails. By joves it seemed a lovely country after Egypt and Gallipoli. Everywhere you see lovely fields of grape vines, fruit trees, cultivated land and rivers. The people are a splendid race and women work in the fields like a man. It is a common sight to see them ploughing and hoeing in the fields and we Australians were always greeted the time of day. We often bought bread off them instead of eating biscuits. Our three days trip from Marseilles to a place called Baielui was through the prettiest country I ever saw. We were within 8 miles of Paris and could see the Eiffel Tower plainly. It was a certainty that if they took us through Paris, we would have taken leave and had a look around Paris. We were only a little over a week at Baielui about 10 miles from the trenches. We could plainly hear the booming of the heavy guns.

Well brothers, everyone who goes to the front has narrow escapes and I have had mine. One day in the trenches, previous to doing this raid, Frank Trevillian and I were just killing time and having a sing-song and old Fritz was shelling our part of the trench with a 9 point 5 shell (known amongst the soldiers as coal boxes). Now one of these coal boxes landed two yards in front of the trenches where Frank and I was, and by a piece of luck, missed fire. Had it gone off, we should have been in little pieces? Frank and I looked at one another and then went on singing, but I can tell you, it made us think of better places than that dammed old trench. By Joves, as I sit here and write these lines to you boys, I am indeed thankful I am having a spell from it all and sincerely hope I have no more fighting for a while. I am not afraid to go back, but I think it only right that we old hands should have a spell. I have now six scars from bullets to show, so think that quite sufficient. I had word from Charlie lately saying he was being discharged from hospital, so I am in hopes of seeing him soon. Poor old Bert will miss Charlie very much. I do hope he gets through alright. Fred is very lucky getting his discharge and I am very glad for it will help to cheer up Mother and Dad. I’ll bet you boys are proud of your soldier brothers and you have the satisfaction of saying that none of them were slackers.

Well dear brothers, war is nothing else but pure murder and the sooner it is all over the better for everyone concerned. I am looking forward to the time when it is all over and we can come home again. I guess we will have a good old time. I am positive that at Dad’s spree the champagne will get a severe hiding. I have contracted a terrible thirst since joining the Army. Of course I put it down to Bully Beef.

Well dear brothers, we have some characters in the Australian Army. All kinds from bank clerks to bush whackers. Wherever there is a mix up with fists, some of our boys are in it, but a softer hearted lot you could not find in the whole world. They are ever willing to help a man wounded, or anyone down on his luck. They have taught many an Englishman manners by getting up and giving a lady their seat. They are rough and ready but no matter what country they go to, they are classed as gentlemen. In Hospital over here we are treated with great respect and want for nothing. We get scores of invitations to visit the wealthy peoples’ houses. I have had many an outing and hope for many more similar ones. I have a nice light job now looking after these rooms in a musketry school. I have only to keep them tidy, and can finish them in two hours. The job may last six weeks or six months. I hope it hangs out until the end of the war. Three good meals a day and a nice warm bed to lie on so I can’t growl. Now Leslie and Gordon, I want you to write me a letter and let me know how you are getting on, what kind of work you are doing and if you want to know any particular news about different countries I have been in. Just mention it in your letter and I will be only too pleased to give you any information I can. I will now close, hoping this finds you both well,

I remain your aff brother Henry.

On 16 April 1918 Henry wrote to his mother and his emotional yearning for home and family shows in the letter.

My Dear Mother,

Just a few lines to say I am well and still going strong at the Musketry School. All those rumours of having to go to France again have now died down and we are going on as usual. I am very thankful for I should not like going over there again. I have had all the fighting I want for all time.

Well dear Mother, I was very pleased to receive 6 letters today from Australia, three from you, two from Pauline and one from Charlie and you can guess how pleased I was to hear Charlie had returned home safely. I only wished I could see you all seated down in the old home, so happy and contented all would be.

Well cheerio dear Mother, my time is coming along by next Xmas and don’t forget to keep that Hogshead of beer on ice. Joves, I get thirsty every time I think of it. I guess I can do justice to my share of it. I do not mention Champayne now as I reckon the Australians have drank all that in France. You can bet I had my share when I was there. By Joves, young Gordon is a brick and is sticking to that job in N.S.W. I reckon it will be the making of him. I sincerely hope he sticks to banking his money as he is doing for it is the finest thing for a young fellow to have a few pounds behind him. I really had no idea work was at such a standstill in Australia. Is Leslie a carpenter? For some months back you mentioned that he was working for Mr Musgrove. So Fred is once again Postman. Does he think it better than soldiering? I wish I had half his luck. I suppose Bert is a gentleman, gets out of bed at 6 every morning [I mean 10 ] By Joves, I laughed at Gordon’s letter that you enclosed. He said his boss had been to America, South Sea Islands and Christ knows where [I wonder where that place is] I am very pleased to know Miss Addey writes to you. Every letter I get from her you are mentioned and I have always an invitation to call and see them whenever I can get leave. Charlie will be able to tell you what a lovely home they have and how splendid they treated him and myself. It is indeed a home away from home. I hope Charlie will not forget to write a few lines to her. I was surprised to hear Bob Bruce is in hospital. Still, he is indeed having a bad time of it. Remember me to him when you write.

Well Mum, I will soon be out of the twenties, only a few days to go now and I will be 30 years of age and reckon it quite time I was home and looking after my little son and heir and I am sure he will want a little sister to play with. I am thinking he will soon be following his old dad over here if this war lasts much longer. What a grand time it will be when it is all over and we get back again to dear old Aussie .You cannot imagine how the dear old place appeals to us after being years away. Well dear Mother, I still do the washing here for the Sargeants and it always brings me in a few extra bob. Everything is so very dear over here. Just now, cigarettes are five and a halfpence a packet of 10 and tobacco is nine and a halfpence an ounce. I was very lucky in receiving a lb of Havelock tobacco from Pauline a couple of weeks ago. It is 2/6 a two ounce tin over here. The civil population are having a terrible hard time of it and I do not know how they manage to live, the prices of food stuffs is awful. Thanks very much for papers and paper cuttings. Everything like that is all news to me. So Florrie [Henry’s sister] has another daughter. By Joves, those two mean business and I don’t think it fair, for I have no chance of keeping pace with them. I reckon I will have to knock them out two at a time. Well now my dear Mother, I must close my letter for this time as I will be soon running out of ink or you will be charged extra postage so with fondest love to all and cheerio till Xmas next,

I remain your ever loving son, Henry.

Henry was quite comfortable in the School of Musketry and naturally in no hurry to return to active service but he failed to obey an order given by an N.C.O and was fined 7 days pay on 24 April 1918 and ordered back to active service.

Overseas Training Battalion, Longbridge, Deverill, Near Warminister, Wiltshire, England. 12 July, 1918.

My dear Father,

Just a few lines to say I am well and will in four days time, be going back to France to fight this Hun. I am now in splendid health and can almost tip the scale at 13 stone. I am just about jumping out of my skin with good training we get and do not mind in the least having to go back. It is for you dear people at home that I am thinking. You will worry, but you must buck up for I may be back again in England before this reaches you.

Well Dad, she is some war and is hanging out a long time, years longer than any of us thought, but there is no doubt that America’s millions of men is going to bring us a victory within a few months. Well Dad, I was in hopes of having Christmas back home with you all but will have to again postpone it. Still I guess that Hogshead beer will keep for another year. We must not forget a goodnight then. I guess you were pleased to have Fred, Bert and Charlie home again and don’t forget Dad, I will soon be back, my good luck will always stick. So Dad, I want you all to cheer up, I am going over to the big stouch with a good heart and I want you to keep the home fires burning and don’t let anything happen to that beer.

Your loving son, Henry.

No 1 Command Depot, Sutton Veny, Wiltshire, England.

Dear Leslie,

I have just received a letter from Mother dated 18th April and you were at that time wanting Dad’s and Mother’s consent to join up. Well dear Brother, I certainly admire your pluck for wanting to do your bit, but if this reaches you before you have taken that step, I would like to point out a few of the disadvantages of this rotten life. First of all, you will miss all those comforts you are use to at home and this is more than you can ever dream of. You will be allowed to draw 2 shillings per day [only] and this at the present time is equal to 6 pence in peace time. I am drawing 1 shilling and I cannot keep my self in smokes. You will find the tucker is much harder to take than you are used to at home. I wish I could sit down to a good square meal like Mother can cook but I am on Army rations and I have not any spare shillings to buy any extra. I have to just want. Here is our day’s menu,

Breakfast;1 slice of dark bread with dripping, a small quantity of a greasy looking mess called Curry and Rice, half pint tea minus sugar.

Dinner; Stew, 1 slice bread, rice pudding or sago.

Tea; 1 slice of bread, jam, margarine, half pint tea.

I don’t know if you ever tasted margarine, I hope not.

Now you are bossed and bullied about by Corporals, Sgnts, Officers and LanceJacks from morning till night and you have to do all kinds of unpleasant duties. You cannot refuse unless you like to lose a few days pay and do a few days clink.

Now Les, Just consider yourself well off where you are and try and use your common sense a little. Surely you must admit Mother and Dad have had enough worry over Fred, Bert, Charlie and myself. I am going to France in a couple of week’s time. I will represent you there and as a last wish, I want you to hang on where you are. You can never realise the misery of it all until you have seen some of it. Hoping dear Brother, this finds you well and that you think before enlisting,

Your loving Brother, Henry.

Henry finally returned to his Battalion on 24 July and wrote home again from somewhere in France on 7 August.

My dear Mother, Father, Sisters and Brothers,

I am going into a big fight to-night and would just like write a few lines for one never knows what may happen. I cannot tell you where we are making our drive but you will read of it in the papers. Well dear parents, brothers and sisters, should I go under you will know I have done my duty and have always tried to play the game. I do indeed feel very thankful that Charlie, Bert, and Fred are back home with you. I am going into that great fight with a good heart and with loving thoughts of you all, my ever fondest love to all,

I remain your ever loving son, Henry.

In a following letter on 20 August he wrote to his parents from the Western Front recording his recent battles and his nostalgia for home as he had not been back to Australia for 40 months.

My dear mother,

We just come out from the front line and our Division was supposed to be out for a couple of weeks spell but everything is so indefinite we may have to go in again in a few days time. Well dear Mother, I was very pleased to receive your letter of 23rd June and know you are alright but you must not worry so much about me. I will come through alright and will admit it is a touch different to my job at Tidworth but still don’t mind and guess it is my fate to see it through and dear Mother, I am ever so grateful it has fallen to myself as the eldest of our four boys to carry on. It does indeed make it easier for me to know my younger brothers are safe home. I am applying for my furlough to Australia but of course will probably have to wait my turn. Pauline says in her letter that she is also trying to get me home so between us we may soon have satisfaction. I think I should just about go out of my head at the thought of coming back to Aussie again. We are always hearing news of the 1914 men being relieved from the line but it seems to stop at that. Anyway, I mean to try hard for it.

Well dear Mother, I am pleased to know Charlie is going through the operation to his arm and do hope it will be a success. I am also pleased to know Bert, Fred and Leslie are working and hope Leslie has changed his mind about joining up and hope Dad is all right again. I reckon Dad ought to have a spell for good, he has done his share. Still dear Mother, I know Dad would not be satisfied with nothing to do. I still have that snap that Fred took of Dad in the garden and like it very much. It brings back memories of that day Charlie and I were told to weed the peas but we went off bird nesting. When we came home for tea, we had to set to and do the weeding anyway. Well, they were good old times and we boys had as good a home as anyone could have wished for. I received a letter from Charlie, Les and Fred by the same mail as yours but I will owe them a letter as we are limited in sending letters and I want to make certain of one for you and Pauline every week.

Well dear Mother, I have made a lot of friends since coming back to the trenches but I cannot say they are nice ones. They are grey in colour and have legs on both sides. Some say Keating’s powder is good but I think a change in flannels much better. People say ‘chats’[lice] will not live on a person in poor health. I must be in tiptop health. Well now dear Mother, I draw my letter to a close hoping this finds you all in the best of health and fondest love to all.

I remain your loving son Henry.

This was Henry’s last letter. He was killed by shellfire around 4pm on 19 September in the Ascension Wood area south west of Bellicourt. His family was notified of his death by the Reverend, Mr Madsen of Richardson Street, Essendon.

A letter (below) from the Defence Department explains why there is no known grave even though the grave marker on the left indicated a burial location.The third image is a newspaper article in memory of Henry.

After the war on 3 February 1919, Henry’s wife Pauline wrote to the Australian Base Records Department.

Dear Sir,