WIMEREUX COMMUNAL CEMETERY

Pas De Calais

France

GPS Coordinates: Latitude: 50.77389, Longitude: 1.61333

Roll of Honour

Listed by Surname

Location Information

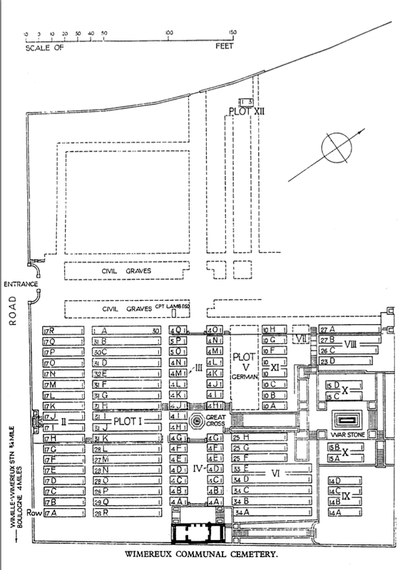

Wimereux is a small town situated approximately 5 kilometres north of Boulogne.

From the centre of Boulogne take the A16 to Calais and exit at junction 33. Follow the D242 into Wimereux and at the first roundabout in town, take the third exit, continuing on the D242 and after approximately 200 yards, turn left into a one way road. The Cemetery lies at the end of this road.

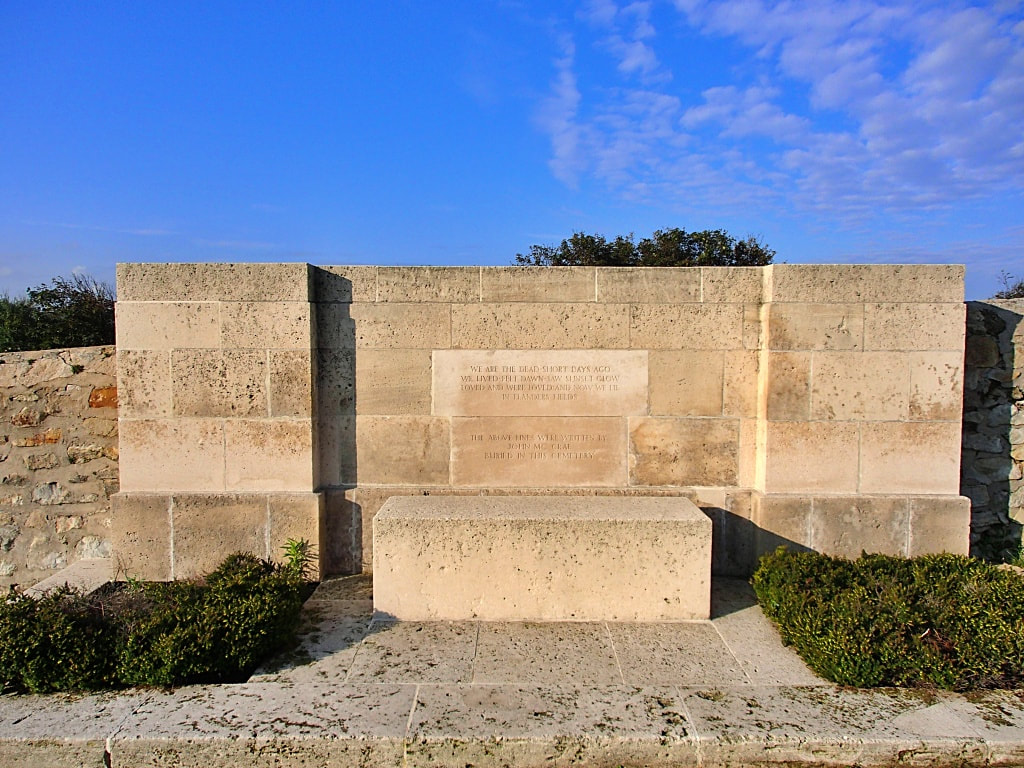

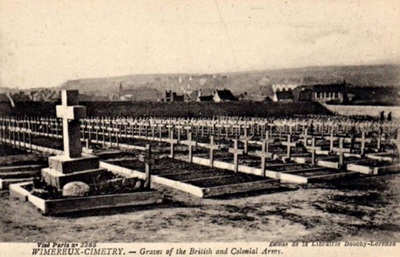

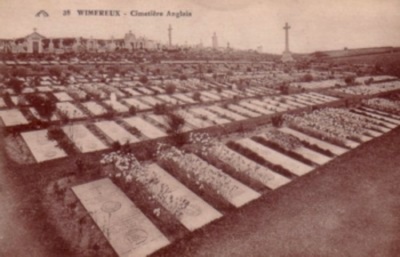

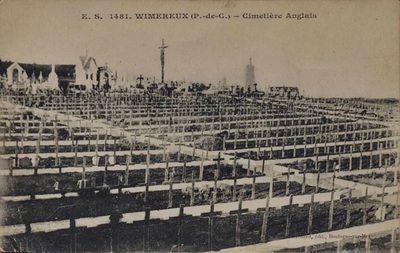

The Commonwealth War Graves are situated to the rear of the Communal Cemetery. Because of the sandy nature of the soil, the headstones lie flat upon the graves.

Visiting Information

The opening hours are :

on 1st November to 31 March on 8.00 to 17.00

on 1st April to 31 October on 8.00 to 19.0

Wheelchair access to this cemetery is possible with some difficulty.

Historical Information

Wimereux was the headquarters of the Queen Mary's Army Auxilliary Corps during the First World War and in 1919 it became the General Headquarters of the British Army.

From October 1914 onwards, Boulogne and Wimereux formed an important hospital centre and until June 1918, the medical units at Wimereux used the communal cemetery for burials, the south-eastern half having been set aside for Commonwealth graves, although a few burial were also made among the civilian graves. By June 1918, this half of the cemetery was filled, and subsequent burials from the hospitals at Wimereux were made in the new military cemetery at Terlincthun.

During the Second World War, British Rear Headquarters moved from Boulogne to Wimereux for a few days in May 1940, prior to the evacuation of the British Expeditionary Force from Dunkirk. Thereafter, Wimereux was in German hands and the German Naval Headquarters were situated on the northern side of the town. After D-Day, as Allied forces moved northwards, the town was shelled from Cap Griz-Nez, and was re-taken by the Canadian 1st Army on 22 September 1944.

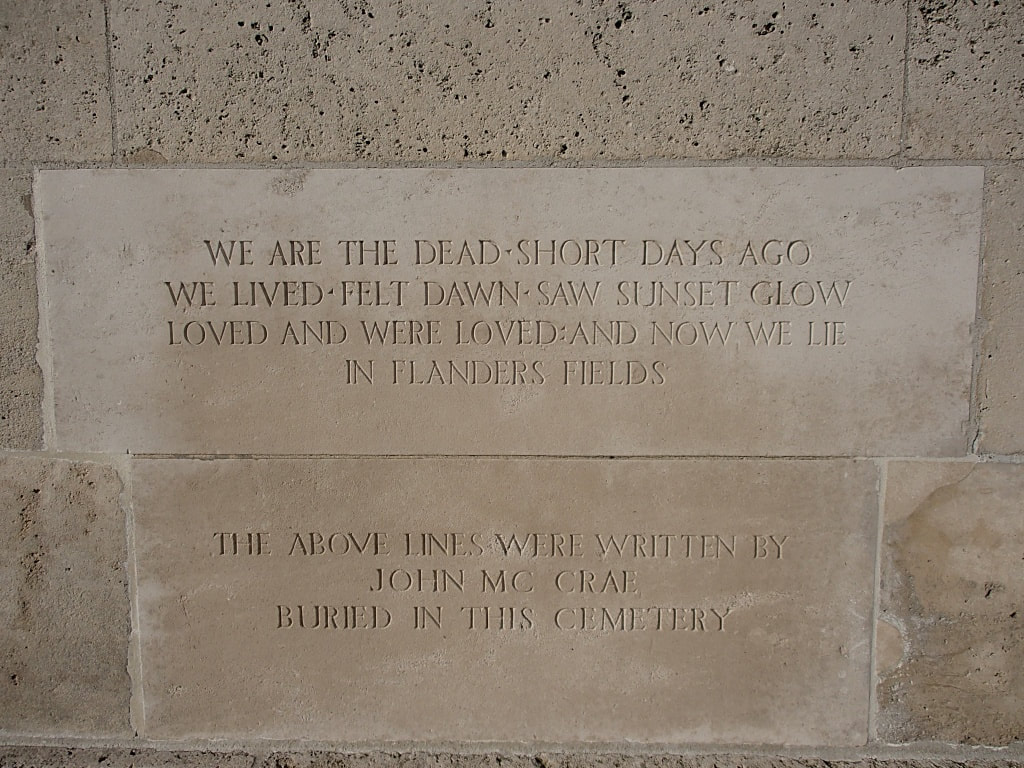

Buried here is Lt.-Col. John McCrae, author of the poem "In Flanders Fields.

There are also five French and a plot of 170 German war graves. The cemetery also contains 14 Second World War burials, six of them unidentified.

Total Burials: 3,036.

Commonwealth Identified Casualties World War One: United Kingdom 2328, Canada 220, Australia 208, New Zealand 79, South Africa 10. Total 2,845.

Other Nationalities: World War One: Germany 170, France 5. Total 175.

Commonwealth Identified Casualties World War Two: United Kingdom 8.

Unidentified Casualties World War Two: 6.

The Commonwealth section was designed by Charles Holden and William Harrison Cowlishaw

This cemetery is the burial place of the Canadian medical officer, Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, who in 1915 wrote the celebrated poem "In Flanders Fields". His grave is shown below (Image courtesy of Mike Booker).

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Informal portrait of Lieutenant Colonel (Lieut Col) John McCrae of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, who wrote the famous First World War poem, 'In Flanders Fields'. It was from the theme of the poem that the annual Poppy Day Appeal to aid funds for the alleviation of distress among widows and dependants of servicemen was inspired. The red poppy was also adopted as an emblem of remembrance. Colonel McCrae died on active service on the 28 January 1918 and was buried at Wimereux in France. Lieut Col McCrae is seen here playing with a dog.

Images in this gallery © Geerhard Joos

Doing their Bit - The Voluntary Aid Detachment

by Janine Lawrence

Over the centuries the history of our country has been littered with governmental mistakes and mishaps. How refreshing then, that in 1908 the new Secretary of State for War, Lord Haldane, undertook reforms in the army which were to have far-reaching effects.

He established a new part-time army of volunteers who were fully-trained soldiers in full-time jobs and who were organised on a county system. This Territorial Force became jokingly known as the 'Saturday Night Soldiers' as the young men who joined were taught to shoulder arms at weekly meetings and drills. They even attended summer camp and many 'Terriers' were at camp when war was declared in August 1914.

In 1909, with unbelievable foresight, the War Office issued a 'Scheme for the Organisation of Voluntary Aid in England and Wales' which recognised the need to provide sufficient medical backup to supplement the Territorial Force in the event of war. Ultimate efficiency would not be realised unless all voluntary aid was co-ordinated and the Territorial Associations were directed to entrust the work to the British Red Cross which had also adopted the county system of organisation. They joined up with the Order of St John of Jerusalem and thus, the organisation known as the Voluntary Aid Detachment was born.

Detachments were divided into those for men and those for women. Men's detachments numbered 56 lead by a commandant and comprising a medical officer, a quartermaster, a pharmacist and four section leaders each responsible for 12 men. They were usually responsible for transport and converting suitable buildings into hospitals and clearing stations and would also act as stretcher-bearers and male nurses if required. After enrolment the men studied first aid and were lectured in the various duties connected with transport and camps.

The women's detachments were less than half the strength of the men. They were also led by a commandant, who could either be male or female and not necessarily a doctor, a quartermaster, a trained nurse as a lady superintendent and 20 women of whom four had to be qualified cooks. It was felt the women's detachments would be better served to the 'less arduous' task of forming railway rest stations where they could prepare and serve meals for sick and wounded soldiers. It was obvious they were seen more as domestic assistants than nurses! However, they were given lectures in first aid, home nursing, hygiene and cookery and were occasionally given training in infirmaries. They were taught to identify suitable buildings for use as temporary hospitals and how to obtain equipment and supplies.

Within a year membership numbered somewhere around 6000 with over 2,500 detachments. These numbers increased considerably after the outbreak of war in 1914 and numbers rose to over 74,000, two-thirds of whom were women and girls.

As men were called away to answer their country's call it fell upon the women to fill their shoes in whatever way they could. Initially it was mostly middle-class women who were eager to 'do their bit' and they took on roles such as ambulance drivers, welfare officers, fundraisers, civil defence workers and even letter writers for the illiterate. It is interesting to note that the novelist, Agatha Christie was a VAD and worked in a hospital pharmacy where she learned about poisons!

The military authorities were reluctant at this early stage to accept VADs on the front line, perhaps thinking that the battlefield was no place for a woman. However, this restriction was lifted in 1915 and women volunteers over the age of twenty three and with more than three months experience were allowed to go to the Western Front, Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. Eventually VAD's were also sent to the Eastern Front.

Before the outbreak of war some VADs had taken short nursing courses for which they were awarded certificates. Qualified nurses had undertaken three years training and were understandably suspicious of these short courses, referring to the volunteers as 'ignorant amateurs'. Quarrels broke out and there are even reports of open conflict before the new spirit of unity in time of war was felt and working together for mutual benefit was the order of the day.

The VAD's became very active in the war effort using influence to transport themselves to the conflicts in France to care for the sick and wounded and thus carving out for themselves a clear role as nurses or orderlies in hospitals at home and in the theatres of war. By 1916 their numbers had increased to 80,000.

In 1917 clear regulations were laid down by the British Red Cross which governed the employment of nursing VAD's in military hospitals. Age limits were specified and volunteers should be between 21 and 48 years of age for home service and 23 and 42 for foreign. They were to be appointed for one month on probation during which time they were assessed for suitability by the matron. They then had to sign an agreement to serve for six months or the duration of the war, at home or abroad. Salary would be £20 per annum rising to £22.10.0 for those who signed on for another six months at the end of their current contract. Increments of a further £2.10.0 would be paid every six months until probationers reached the maximum of £30 per annum.

It was also laid down that VAD's should work under fully trained nurses with duties including sweeping, dusting, polishing, cleaning, washing patients' crockery, sorting linen and any nursing duties allotted by the matron.

Meanwhile, VAD hospitals were being set up in Blighty and were mostly located in large houses loaned for the purpose by their owners. Gustard Wood at Wheathampstead and The Bury at King's Walden are just two Hertfordshire premises used. The Council School in Royston and the former mental hospital, Napsbury in Colney Heath are examples of institutes put into service.

These hospitals received the sum of three shillings per day per patient from the War Office and were expected to raise additional funds themselves. As everyone was keen to be seen to help the war effort this was not difficult and local newspapers regularly featured lists of donations received - obviously anonymity did not seem to be the case!

Many women returning home after the conflict ended undertook formal nurse training and registration with the General Nursing Council. Others tried to pick up the threads of their former lives. What must be certain is that life could never have been the same for any of them again. The sight, smell and fear of war must have been imprinted on every mind bringing about a change in the lives of women which would grow and grow over the following years.

Our thanks to Janine Lawrence for permission to use this article

© Janine Lawrence

by Janine Lawrence

Over the centuries the history of our country has been littered with governmental mistakes and mishaps. How refreshing then, that in 1908 the new Secretary of State for War, Lord Haldane, undertook reforms in the army which were to have far-reaching effects.

He established a new part-time army of volunteers who were fully-trained soldiers in full-time jobs and who were organised on a county system. This Territorial Force became jokingly known as the 'Saturday Night Soldiers' as the young men who joined were taught to shoulder arms at weekly meetings and drills. They even attended summer camp and many 'Terriers' were at camp when war was declared in August 1914.

In 1909, with unbelievable foresight, the War Office issued a 'Scheme for the Organisation of Voluntary Aid in England and Wales' which recognised the need to provide sufficient medical backup to supplement the Territorial Force in the event of war. Ultimate efficiency would not be realised unless all voluntary aid was co-ordinated and the Territorial Associations were directed to entrust the work to the British Red Cross which had also adopted the county system of organisation. They joined up with the Order of St John of Jerusalem and thus, the organisation known as the Voluntary Aid Detachment was born.

Detachments were divided into those for men and those for women. Men's detachments numbered 56 lead by a commandant and comprising a medical officer, a quartermaster, a pharmacist and four section leaders each responsible for 12 men. They were usually responsible for transport and converting suitable buildings into hospitals and clearing stations and would also act as stretcher-bearers and male nurses if required. After enrolment the men studied first aid and were lectured in the various duties connected with transport and camps.

The women's detachments were less than half the strength of the men. They were also led by a commandant, who could either be male or female and not necessarily a doctor, a quartermaster, a trained nurse as a lady superintendent and 20 women of whom four had to be qualified cooks. It was felt the women's detachments would be better served to the 'less arduous' task of forming railway rest stations where they could prepare and serve meals for sick and wounded soldiers. It was obvious they were seen more as domestic assistants than nurses! However, they were given lectures in first aid, home nursing, hygiene and cookery and were occasionally given training in infirmaries. They were taught to identify suitable buildings for use as temporary hospitals and how to obtain equipment and supplies.

Within a year membership numbered somewhere around 6000 with over 2,500 detachments. These numbers increased considerably after the outbreak of war in 1914 and numbers rose to over 74,000, two-thirds of whom were women and girls.

As men were called away to answer their country's call it fell upon the women to fill their shoes in whatever way they could. Initially it was mostly middle-class women who were eager to 'do their bit' and they took on roles such as ambulance drivers, welfare officers, fundraisers, civil defence workers and even letter writers for the illiterate. It is interesting to note that the novelist, Agatha Christie was a VAD and worked in a hospital pharmacy where she learned about poisons!

The military authorities were reluctant at this early stage to accept VADs on the front line, perhaps thinking that the battlefield was no place for a woman. However, this restriction was lifted in 1915 and women volunteers over the age of twenty three and with more than three months experience were allowed to go to the Western Front, Gallipoli and Mesopotamia. Eventually VAD's were also sent to the Eastern Front.

Before the outbreak of war some VADs had taken short nursing courses for which they were awarded certificates. Qualified nurses had undertaken three years training and were understandably suspicious of these short courses, referring to the volunteers as 'ignorant amateurs'. Quarrels broke out and there are even reports of open conflict before the new spirit of unity in time of war was felt and working together for mutual benefit was the order of the day.

The VAD's became very active in the war effort using influence to transport themselves to the conflicts in France to care for the sick and wounded and thus carving out for themselves a clear role as nurses or orderlies in hospitals at home and in the theatres of war. By 1916 their numbers had increased to 80,000.

In 1917 clear regulations were laid down by the British Red Cross which governed the employment of nursing VAD's in military hospitals. Age limits were specified and volunteers should be between 21 and 48 years of age for home service and 23 and 42 for foreign. They were to be appointed for one month on probation during which time they were assessed for suitability by the matron. They then had to sign an agreement to serve for six months or the duration of the war, at home or abroad. Salary would be £20 per annum rising to £22.10.0 for those who signed on for another six months at the end of their current contract. Increments of a further £2.10.0 would be paid every six months until probationers reached the maximum of £30 per annum.

It was also laid down that VAD's should work under fully trained nurses with duties including sweeping, dusting, polishing, cleaning, washing patients' crockery, sorting linen and any nursing duties allotted by the matron.

Meanwhile, VAD hospitals were being set up in Blighty and were mostly located in large houses loaned for the purpose by their owners. Gustard Wood at Wheathampstead and The Bury at King's Walden are just two Hertfordshire premises used. The Council School in Royston and the former mental hospital, Napsbury in Colney Heath are examples of institutes put into service.

These hospitals received the sum of three shillings per day per patient from the War Office and were expected to raise additional funds themselves. As everyone was keen to be seen to help the war effort this was not difficult and local newspapers regularly featured lists of donations received - obviously anonymity did not seem to be the case!

Many women returning home after the conflict ended undertook formal nurse training and registration with the General Nursing Council. Others tried to pick up the threads of their former lives. What must be certain is that life could never have been the same for any of them again. The sight, smell and fear of war must have been imprinted on every mind bringing about a change in the lives of women which would grow and grow over the following years.

Our thanks to Janine Lawrence for permission to use this article

© Janine Lawrence