SUCRERIE MILITARY CEMETERY

Colincamps

Somme

France

GPS Coordinates Latitude: 50.09567 Longitude: 2.62341

Roll of Honour

Listed by Surname

Location Information

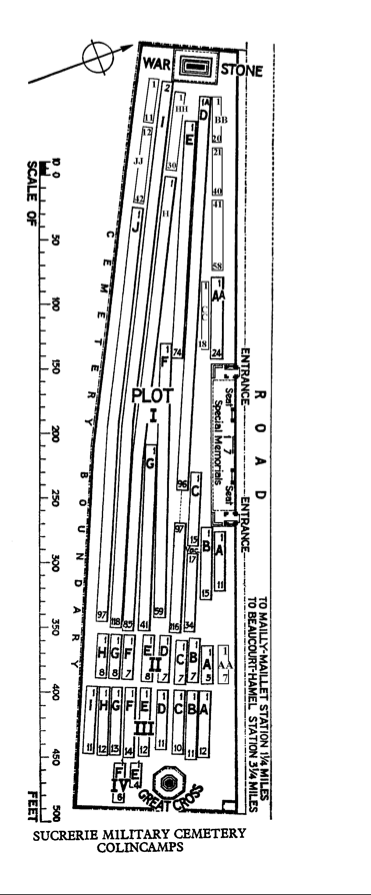

Colincamps is a village about 16 kilometres north of Albert. Sucrerie Military Cemetery is about 3 kilometres south-east of the village on the north side of the road from Mailly-Maillet to Puisieux. The cemetery is on the left; along a 400 metres dirt track.

Visiting Information

Wheelchair Access is possible with some difficulty.

Historical Information

The cemetery was begun by French troops in the early summer of 1915, and extended to the West by British units from July in that year until, with intervals, December 1918. It was called at first the 10th Brigade Cemetery. Until the German retreat in March 1917, it was never more than a 1.6 kilometres from the front line; and from the end of March 1918 (when the New Zealand Division was engaged in fighting at the Sucrerie) to the following August, it was under fire. The 285 French and twelve German graves were removed to other cemeteries after the Armistice, and in consequence there are gaps in the lettering of the Rows.

There are now 1111, 1914-18 war casualties commemorated in this site. Of these 226 casualties are unidentified.

The cemetery covers an area is 6,322 square metres and it is enclosed by a low brick wall.

Total Burials: 1111.

Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 796, New Zealand 62, Australia 14, South Africa 8, Canada 5. Total 885.

Unidentified Casualties: 226.

The cemetery was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and George Hartley Goldsmith

Shot at Dawn

14218 Private James Crozier, 9th Bn. Royal Irish Rifles, executed for desertion 27th February 1916. Plot I. A. 5. Son of Mrs. Elizabeth Crozier, of 80, Battenberg Street, Belfast.

A shipyard apprentice, he enlisted in Sept 1914 — possibly understating his age — & was sent to France in Oct 1915, when his ‘Army age’ was 19.

On 31 Jan 1916, his battalion went into the line at 1900. At 2045,

Crozier disappeared after being warned for sentry duty. He was next seen on 4 Feb, about 25 miles to the rear, being found without cap-badge, equipment or pay-book — & was arrested after admitting that he was a deserter.

At trial, Crozier said that he had felt ill on the day, & did not recall being warned for duty. In cross-examination, he admitted that he had felt ill before going into the lines; that he had not reported sick; & that he had left the trenches when bombardment was taking place.

After conviction, his conduct sheet revealed 2 charges of absence while in France, the latest being recorded on 21 Jan.

His CO — who said later in his memoirs that he had encouraged Crozier’s enlistment, promising his mother that he would look after him — said that Crozier was valueless as a soldier, having been a shirker for the previous 3 months. The Brigade commander recommended execution, but at Divisional level a medical examination was decided on. The finding on 18 Feb was that Crozier was, & had been sound in mind & body.

The CO related that he had attended at the time appointed for execution, having beforehand made Crozier drunk to ease his misery. ‘The whole battalion heard it on parade, a wall screening the victim from the men’s view’. The Assistant Provost Marshal & the Military Police were — anomalously — kept away from the scene, apparently because it was feared that the battalion would mutiny & might refuse to shoot; & in the event the squad fired wide.

(Corns, pp, 304-307)

14218 Private James Crozier, 9th Bn. Royal Irish Rifles, executed for desertion 27th February 1916. Plot I. A. 5. Son of Mrs. Elizabeth Crozier, of 80, Battenberg Street, Belfast.

A shipyard apprentice, he enlisted in Sept 1914 — possibly understating his age — & was sent to France in Oct 1915, when his ‘Army age’ was 19.

On 31 Jan 1916, his battalion went into the line at 1900. At 2045,

Crozier disappeared after being warned for sentry duty. He was next seen on 4 Feb, about 25 miles to the rear, being found without cap-badge, equipment or pay-book — & was arrested after admitting that he was a deserter.

At trial, Crozier said that he had felt ill on the day, & did not recall being warned for duty. In cross-examination, he admitted that he had felt ill before going into the lines; that he had not reported sick; & that he had left the trenches when bombardment was taking place.

After conviction, his conduct sheet revealed 2 charges of absence while in France, the latest being recorded on 21 Jan.

His CO — who said later in his memoirs that he had encouraged Crozier’s enlistment, promising his mother that he would look after him — said that Crozier was valueless as a soldier, having been a shirker for the previous 3 months. The Brigade commander recommended execution, but at Divisional level a medical examination was decided on. The finding on 18 Feb was that Crozier was, & had been sound in mind & body.

The CO related that he had attended at the time appointed for execution, having beforehand made Crozier drunk to ease his misery. ‘The whole battalion heard it on parade, a wall screening the victim from the men’s view’. The Assistant Provost Marshal & the Military Police were — anomalously — kept away from the scene, apparently because it was feared that the battalion would mutiny & might refuse to shoot; & in the event the squad fired wide.

(Corns, pp, 304-307)