POPERINGHE NEW MILITARY CEMETERY

West-Vlaanderen

Belgium

GPS Coordinates Latitude: 50.84738 Longitude: 2.73305

Location Information

Poperinghe New Military Cemetery is located 10.5 Kms west of Ieper town centre, in the town of Poperinge itself. From Ieper, Poperinge is reached via the N308.

From Ieper town centre the Poperingseweg (N308), is reached via Elverdingsestraat then directly over two small roundabouts in the J. Capronstraat. The Poperingseweg is a continuation of the J. Capronstraat and begins after a prominent railway level crossing. On reaching the town of Poperinge, the left hand turning from the N308 leads onto the R33 Poperinge ring road. 1 Km along the R38 lies the right hand turning onto Deken De Bolan. The cemetery is located 100 metres from the ring road level with Onze Vrouwedreef on the right hand side of the road.

Visiting Information

Wheelchair access to the site is possible, but may be by an alternative entrance.

Historical Information

The town of Poperinghe (now Poperinge) was of great importance during the First World War because, although occasionally bombed or bombarded at long range, it was the nearest place to Ypres (now Ieper) which was both considerable in size and reasonably safe. It was at first a centre for Casualty Clearing Stations, but by 1916 it became necessary to move these units further back and field ambulances took their places.

The earliest Commonwealth graves in the town are in the communal cemetery. The Old Military Cemetery was made in the course of the First Battle of Ypres and was closed, so far as Commonwealth burials are concerned, at the beginning of May 1915. The New Military Cemetery was established in June 1915.

The New Military Cemetery contains 677 Commonwealth burials of the First World War and 271 French war graves.

Total Burials: 953.

Commonwealth Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 596, Canada 55, Australia 20, New Zealand 3. Total 574.

Commonwealth Unidentified Casualties: 103.

Other Nationalities: France 271, Belgium 2, Germany 1. Total 274.

The cemetery was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and Noel Ackroyd Rew

Poperinghe New Military Cemetery is located 10.5 Kms west of Ieper town centre, in the town of Poperinge itself. From Ieper, Poperinge is reached via the N308.

From Ieper town centre the Poperingseweg (N308), is reached via Elverdingsestraat then directly over two small roundabouts in the J. Capronstraat. The Poperingseweg is a continuation of the J. Capronstraat and begins after a prominent railway level crossing. On reaching the town of Poperinge, the left hand turning from the N308 leads onto the R33 Poperinge ring road. 1 Km along the R38 lies the right hand turning onto Deken De Bolan. The cemetery is located 100 metres from the ring road level with Onze Vrouwedreef on the right hand side of the road.

Visiting Information

Wheelchair access to the site is possible, but may be by an alternative entrance.

Historical Information

The town of Poperinghe (now Poperinge) was of great importance during the First World War because, although occasionally bombed or bombarded at long range, it was the nearest place to Ypres (now Ieper) which was both considerable in size and reasonably safe. It was at first a centre for Casualty Clearing Stations, but by 1916 it became necessary to move these units further back and field ambulances took their places.

The earliest Commonwealth graves in the town are in the communal cemetery. The Old Military Cemetery was made in the course of the First Battle of Ypres and was closed, so far as Commonwealth burials are concerned, at the beginning of May 1915. The New Military Cemetery was established in June 1915.

The New Military Cemetery contains 677 Commonwealth burials of the First World War and 271 French war graves.

Total Burials: 953.

Commonwealth Identified Casualties: United Kingdom 596, Canada 55, Australia 20, New Zealand 3. Total 574.

Commonwealth Unidentified Casualties: 103.

Other Nationalities: France 271, Belgium 2, Germany 1. Total 274.

The cemetery was designed by Sir Reginald Blomfield and Noel Ackroyd Rew

Cemetery images in this gallery © Werner Van Caneghem

Shot at Dawn Headstones in this gallery © Geerhard Joos

Shot at Dawn

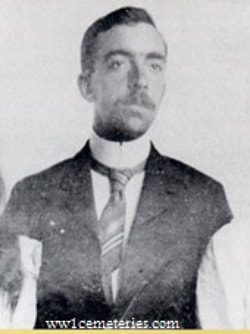

Second Lieutenant

Eric Skeffington Poole

11th Bn. West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales's Own)

Executed for desertion on 10th December 1916, aged 31.

Plot II. A. 11.

His headstone bears the inscription "Grant Him Eternal Rest O Lord Jesu' Mercy"

Son of Henry Skeffington Poole and Florence Hope Gibsone Poole, of 2, Rectory Place, Guildford, Surrey. Born Nova Scotia.

Having been born & lived in Canada, he served 2 years as a Lieutenant in the Militia. His family moved to England where he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in April 1915.

On 5 Oct 1916, his battalion carried out a relief of the front line trenches at Flers, but Poole went missing, being found by the RMP on 7 Oct at Henencourt. His CO ordered a regimental court of inquiry, as a result of which a charge sheet was drawn up, alleging an offence of absence with intent to avoid duty. On 17 Oct, the Brigade commander— to whom the court’s findings were forwarded — noted that Poole had been admitted to hospital suffering from shell-shock in early July; opined that Poole was ‘of nervous temperament, useless in action, & dangerous as an example to the men’; & recommended that he be sent away from the firing line as soon as possible, & usefully employed elsewhere.

2 days later an RAMC Lieut Colonel examined Poole & found that he had a highly-strung, neurotic temperament, & that excitement might ‘bring on a condition of mental aberration which would make him not responsible to his actions’.

On 25 Oct, the Army commander decided on a court martial on a charge of desertion. Before trial, the defending officer sought a medical board to examine the man he was to represent, but this was refused ‘in the absence of strong grounds’, & the point made that it was open to the accused to call medical evidence at trial.

At trial, the CO said that he knew Poole had been in hospital; & that Poole was rather stupid. Another defence witness said that, on the morning of 5 Oct, Poole had said that he felt ‘damned bad’ & had thought of seeing a doctor; & had also mentioned ‘a touch of rheumatism’.

It further emerged that on 7 Oct, when Poole was found, he was wearing a private’s tunic with a star on each shoulder strap, & a leather jacket over the tunic, the Quartermaster who collected him finding him ‘very dazed’, ‘very confused’ & seemingly not responsible for his actions (he had seen him in the same state in August); but that Poole appeared much better after a night’s rest.

In his own evidence, Poole said that he had been sent to hospital with shell-shock in July, rejoining his unit about 1 Sept; that on 5 Oct, he had left no-one in charge of his platoon, & had told no-one that he was leaving, being confused & with great difficulty in making up his mind. A defence witness who had known Poole in England gave his view that in times of stress or under shell-fire, Poole might become so confused as not to be responsible for his action.

After conviction, the CO doubted that Poole would have realised the seriousness of his actions, while the Brigade commander suggested that Poole had merely ‘wandered away aimlessly’. The Divisional & Corps commanders recommended commutation, but the Army commander disagreed.

However before the final stage of confirmation, a Medical Board was appointed. The medical history before it showed Poole’s classification as shell-shocked on 7 July; his hospital treatment thereafter; & the final opinion that Poole was unfit for duty, & should be sent to temporary base duty. However on arrival at the Base Depot, he was classified as ‘A’ (fit for duty). The Medical Board reported that Poole was (1) on 5 Oct, of sound mind & capable of appreciating the nature & quality of his action in absenting himself, & that such an act was wrong; & (2) that he was at the time of examination of sound mind.

Sentence was confirmed on 6 Dec 1916, Haig stating in his diary that ‘it is highly important that all ranks should realize that the law is the same for an officer as a private’.

Of the 46 officers tried for desertion during the war, 4 death sentences were awarded, Poole being 1 of the only 2 executed. (Corns, pp. 325-336)

Eric Skeffington Poole

11th Bn. West Yorkshire Regiment (Prince of Wales's Own)

Executed for desertion on 10th December 1916, aged 31.

Plot II. A. 11.

His headstone bears the inscription "Grant Him Eternal Rest O Lord Jesu' Mercy"

Son of Henry Skeffington Poole and Florence Hope Gibsone Poole, of 2, Rectory Place, Guildford, Surrey. Born Nova Scotia.

Having been born & lived in Canada, he served 2 years as a Lieutenant in the Militia. His family moved to England where he was commissioned as a Second Lieutenant in April 1915.

On 5 Oct 1916, his battalion carried out a relief of the front line trenches at Flers, but Poole went missing, being found by the RMP on 7 Oct at Henencourt. His CO ordered a regimental court of inquiry, as a result of which a charge sheet was drawn up, alleging an offence of absence with intent to avoid duty. On 17 Oct, the Brigade commander— to whom the court’s findings were forwarded — noted that Poole had been admitted to hospital suffering from shell-shock in early July; opined that Poole was ‘of nervous temperament, useless in action, & dangerous as an example to the men’; & recommended that he be sent away from the firing line as soon as possible, & usefully employed elsewhere.

2 days later an RAMC Lieut Colonel examined Poole & found that he had a highly-strung, neurotic temperament, & that excitement might ‘bring on a condition of mental aberration which would make him not responsible to his actions’.

On 25 Oct, the Army commander decided on a court martial on a charge of desertion. Before trial, the defending officer sought a medical board to examine the man he was to represent, but this was refused ‘in the absence of strong grounds’, & the point made that it was open to the accused to call medical evidence at trial.

At trial, the CO said that he knew Poole had been in hospital; & that Poole was rather stupid. Another defence witness said that, on the morning of 5 Oct, Poole had said that he felt ‘damned bad’ & had thought of seeing a doctor; & had also mentioned ‘a touch of rheumatism’.

It further emerged that on 7 Oct, when Poole was found, he was wearing a private’s tunic with a star on each shoulder strap, & a leather jacket over the tunic, the Quartermaster who collected him finding him ‘very dazed’, ‘very confused’ & seemingly not responsible for his actions (he had seen him in the same state in August); but that Poole appeared much better after a night’s rest.

In his own evidence, Poole said that he had been sent to hospital with shell-shock in July, rejoining his unit about 1 Sept; that on 5 Oct, he had left no-one in charge of his platoon, & had told no-one that he was leaving, being confused & with great difficulty in making up his mind. A defence witness who had known Poole in England gave his view that in times of stress or under shell-fire, Poole might become so confused as not to be responsible for his action.

After conviction, the CO doubted that Poole would have realised the seriousness of his actions, while the Brigade commander suggested that Poole had merely ‘wandered away aimlessly’. The Divisional & Corps commanders recommended commutation, but the Army commander disagreed.

However before the final stage of confirmation, a Medical Board was appointed. The medical history before it showed Poole’s classification as shell-shocked on 7 July; his hospital treatment thereafter; & the final opinion that Poole was unfit for duty, & should be sent to temporary base duty. However on arrival at the Base Depot, he was classified as ‘A’ (fit for duty). The Medical Board reported that Poole was (1) on 5 Oct, of sound mind & capable of appreciating the nature & quality of his action in absenting himself, & that such an act was wrong; & (2) that he was at the time of examination of sound mind.

Sentence was confirmed on 6 Dec 1916, Haig stating in his diary that ‘it is highly important that all ranks should realize that the law is the same for an officer as a private’.

Of the 46 officers tried for desertion during the war, 4 death sentences were awarded, Poole being 1 of the only 2 executed. (Corns, pp. 325-336)

4242 Private

Reginald Thomas Tite

13th Bn. Royal Sussex Regiment

Executed for cowardice on 25th November 1916, aged 27.

Plot II. F. 9.

Son of Mrs. Harriet J. Tite, of 56, Downes St., Old Kent Road, Peckham.

On the morning of 9 Oct 1916, when the battalion trenches were under fire, Tite was in a Lewis gun team, & asked to leave the trench. This was refused, but he was shown a safe place nearby. Tite seems to have gone missing for a short while, but reported back c 1230. Given further duty in the trench, he left, telling a sergeant that he could not stay in the line. When ordered back, he said that he couldn’t stick it.

At trial, he said (but not on oath): ‘……I am very queer when in the line….When there is bombardment, I seem to take leave of my senses…..I have to clear out’.

His record showed that he was serving under a suspended sentence of 4 years’ Penal Servitude imposed for Disobedience.

Despite what Tite had said, he was not seen by a doctor, apart from the usual pre-trial examination.

His father, who later lost another son in the war & likewise 2 nephews, seems to have been deceived about the cause of death of this son, for the Death Certificate gives the cause merely as ‘Death’ ! (Corns, pp 206-207, 212; Putkowski, pp. 136-137)

Reginald Thomas Tite

13th Bn. Royal Sussex Regiment

Executed for cowardice on 25th November 1916, aged 27.

Plot II. F. 9.

Son of Mrs. Harriet J. Tite, of 56, Downes St., Old Kent Road, Peckham.

On the morning of 9 Oct 1916, when the battalion trenches were under fire, Tite was in a Lewis gun team, & asked to leave the trench. This was refused, but he was shown a safe place nearby. Tite seems to have gone missing for a short while, but reported back c 1230. Given further duty in the trench, he left, telling a sergeant that he could not stay in the line. When ordered back, he said that he couldn’t stick it.

At trial, he said (but not on oath): ‘……I am very queer when in the line….When there is bombardment, I seem to take leave of my senses…..I have to clear out’.

His record showed that he was serving under a suspended sentence of 4 years’ Penal Servitude imposed for Disobedience.

Despite what Tite had said, he was not seen by a doctor, apart from the usual pre-trial examination.

His father, who later lost another son in the war & likewise 2 nephews, seems to have been deceived about the cause of death of this son, for the Death Certificate gives the cause merely as ‘Death’ ! (Corns, pp 206-207, 212; Putkowski, pp. 136-137)

13216 Serjeant

John Thomas Wall

3rd Bn. Worcestershire Regiment

Executed for desertion on 6th September 1917, aged 22.

Plot II. F. 42.

His headstone bears the inscription "For Ever with The Lord"

Son of William and Harriet Wall, of Hill Cottages, Bockleton, nr. Tenbury, Worcestershire.

Enlisted in 1912, & had served with his battalion in every engagement. Wall disappeared during an attack, no motive for this uncharacteristic behaviour emerging at his subsequent trial. (Putkowski, p 191)

John Thomas Wall

3rd Bn. Worcestershire Regiment

Executed for desertion on 6th September 1917, aged 22.

Plot II. F. 42.

His headstone bears the inscription "For Ever with The Lord"

Son of William and Harriet Wall, of Hill Cottages, Bockleton, nr. Tenbury, Worcestershire.

Enlisted in 1912, & had served with his battalion in every engagement. Wall disappeared during an attack, no motive for this uncharacteristic behaviour emerging at his subsequent trial. (Putkowski, p 191)

3/4071 Private J. Bennett, 1st Bn. Hampshire Regiment, executed for cowardice on 28th August 1916, aged 19. Plot II. J. 7. Son of John Bennett, of 37, Vernon Rd., Bow, London.

He enlisted in June 1914, but because of his youth was not sent to France till Nov 1915. On 8 Aug 1916 his battalion was serving in the Ypres Salient, when at c 2200 he was seen to don his smoke helmet when the gas alarm was sounded & half an hour later was found missing when his platoon was to move forward. In the early hours of the next day, Bennett was seen c ¾ of a mile to the rear, saying that he had lost his nerve & had climbed out of the trench; & when he had returned, his company had gone.

In evidence at trial, Bennett said that he had climbed out of the trench into a shell-hole, without knowing what he was doing, & not remembering anything after that. He added that because of a previous similar occurrence he was awaiting a medical inspection — an assertion later reported to be untrue.

His record was a bad one: offences of non-compliance with orders in the UK + 2 years’ imprisonment with hard labour imposed for absence, probably from the fighting on the Somme. His CSM said that he was absolutely useless, & readily went to pieces. The CO related that most of Bennett’s 9 months with the BEF had been spent in hospital or with the transport, adding that a man of such disposition (who may not have known what he was doing) was a positive danger anywhere in the firing line, his conduct capable of giving rise to panic among his comrades. The Brigade commander recommended commutation since Bennett had apparently been too terrified to know what he was doing, but the Divisional & Corps commanders disagreed, the latter writing that: ‘Cowards of this sort are a serious danger’, & that the death penalty was provided in order to make men fear running away more than they feared the enemy. The Army commander concurred. (Corns, pp197-199,212)

12772 Private Albert Botfield, 9th Bn. South Staffordshire Regiment, executed for cowardice on 18th October 1916, aged 28. Plot II. F. 7.

He enlisted in Sept 1914, & in Sept 1916 was serving in a pioneering battalion. In the evening of 21 Sept, Bennett’s platoon were digging new trenches SE of Pozières, when at c 1915 a shell burst near by. Bennett ran away — & was seen returning to his bivouac at 0700 the next day.

At trial, he said on oath that when the shell burst he jumped into the trench & after things had quietened down he went to look for his party but was told that he was going in the wrong direction. He then sat down & slept till c 0400 — an account that varied slightly under cross-examination. Questioned by the court, Bennett said ‘I was nervous that’s why I took so long to come home’.

As to his record: in Jan 1916 he received 90 days’ Field Punishment No 1 for absenting himself from his reinforcement draft for a week; in June, another 28 days for 2 offences of absence; & in September a further 90 days, again for absence — a sentence probably still being served at the time of his final offence. The sentence of death was endorsed by all the unit commanders. (Corns, pp 200-202,212).

34595 Private James Crampton, 9th Bn. Yorks & Lancs Regiment, executed for desertion on 4th February 1917, aged 39. Plot II. B. 14 (D)

He had served 4½ months at Gallipoli when his unit was transferred to the front line in France. Crampton made off & was arrested 3 months later in Armentières — without his equipment. His plea at trial that he must have been ill led to medical examination — which availed him nothing. (Putkowski, p. 160)

8833 Private George Everill, 1st Bn. North Staffordshire Regiment, executed for desertion on 14th September 1917, aged 30. Plot II. F. 44. Son of Mrs. E. Everill, of 40, Mount Pleasant, Shelton, Hanley; husband of Mrs. L. Everill, of 7, Southampton St., Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent.

On separate occasions over c 18 months, he was convicted of using insubordinate language; wilful defiance; absence; & using threatening language. Following his punishment for the last offence, he was convicted again of wilful defiance, for which he was serving Field Punishment, when he was warned to be ready to move up for active operations. When mustered later in the day, he managed to absent himself — leaving his rifle & equipment behind — but was found & arrested the next day. At trial, the accused questioned no witness & made no statement of his own. (Putkowski, p 193-194)

16120 Private John W. Fryer, 12th (Bermondsey) Bn. East Surrey Regiment, executed for desertion on 14th June 1917, aged 23. Plot II. D. 14.

He deserted when serving under a suspended sentence of 2 years’ imprisonment imposed for a previous offence of Desertion. (Putkowski, pp 174-175)

15605 Private Frederick C. Gore, 7th Bn. The Buffs ( East Kent Regiment), executed for desertion on 16th October 1917, aged 19. Plot II. J. 34.

On 10 Aug 1917, when serving near Ypres, he was warned for parade, but soon went missing. Gore was next heard of on 19 Aug, when he presented himself at Boulogne, saying that he was a deserter from Etaples. He was wearing uniform, & gave his correct name & regiment.

At trial, his written statement said that he had deserted ‘because I cannot stand the strain of the shell-fire owing to the very bad state of my nerves’; & that before he came to France, he had been rejected for service abroad because of his nerves. He added that the MO had said that nothing could be done for him. When questioned, he gave some detail: he had spent 5 weeks in hospital for shell-shock, before being returned to his unit about mid-June 1917; & that he had ‘another shaking up when we were holding the line at the end of July’, after which he was examined only by a stretcher-bearer, & sent back to duty.

His conduct sheet showed 4 offences committed between Mar 1916 & July 1917, one of which related to an absence in Apr 1917, when his Lance Corporal’s stripe was taken away. (Corns, pp. 323-324)

416874 Private Come LaLiberté, 3rd Bn. Canadian Expeditionary Force, executed for desertion on 4th August 1916, aged 25. Plot II. H. 3. Son of Luger and Eugenie Hamel LaLiberté, of 170, St. Ferdinand St., Montreal.

He deserted when his unit was billeted within the Ypres Salient, & was executed in front of his battalion. (Putkowski, pp. 98-99)

2974 Private Bernard McGeehan, 1/8th Bn. King’s Liverpool Regiment, executed for desertion on 2nd November 1916. Plot II. D. 9.

His battalion having suffered considerable losses in attack, he deserted from the renewed action. (Putkowski, p. 128)

23686 Private James S. Michael, 10th Bn. Cameronians, Scottish Rifles, executed for desertion on 24th August 1917. Plot II. H. 24.

He deserted to avoid fighting in the Ypres Salient. (Putkowski, p. 187)

7429 Private Herbert Morris, 6th Bn. British West Indies Regiment, executed for desertion on 20th September 1917, aged 17. Plot II. F. 45. Son of William and Ophelia Morris, of Riversdale P.O., St. Catherine, Jamaica.

A Jamaican, he had enlisted in Dec 1916 in a recruitment drive in the West Indies, & arrived in France in Apr 1917. After brief acclimatisation, the battalion moved to communications duties in the Ypres area. On 20 Aug 1917, Morris went missing from a working party, turning up the next day at the St Martin rest camp at Boulogne, saying that he had been sent there by mistake & was on his way to Le Havre. As he had no rifle, equipment or leave pass, he was arrested.

At trial on 7 Sept, Morris — who was unrepresented — made an unsworn statement, saying that he could not stand the sound of the guns, & that the doctor that he had seen on 19 Aug gave him no satisfaction. Despite this defence, no medical examination was ordered, nor was the doctor called to testify.

2 officers gave evidence that Morris had never given any trouble, & worked willingly, but it further appeared that Morris had gone missing on 16 July, being found in Boulogne the next day — for which 14 days’ Field Punishment No 1 had been imposed. (Corns, p. 300)

G/11296 Private William Henry Simmonds, 23rd Bn. Middlesex Regiment, executed for desertion on 1st December 1916, aged 23. Plot II. E. 9. Son of William and Emily Simmonds, of 18, Sidney Terrace, Bedfont Lane, Feltham, Middlesex.

Deserted from the Somme Front. (Putkowski, p 140)

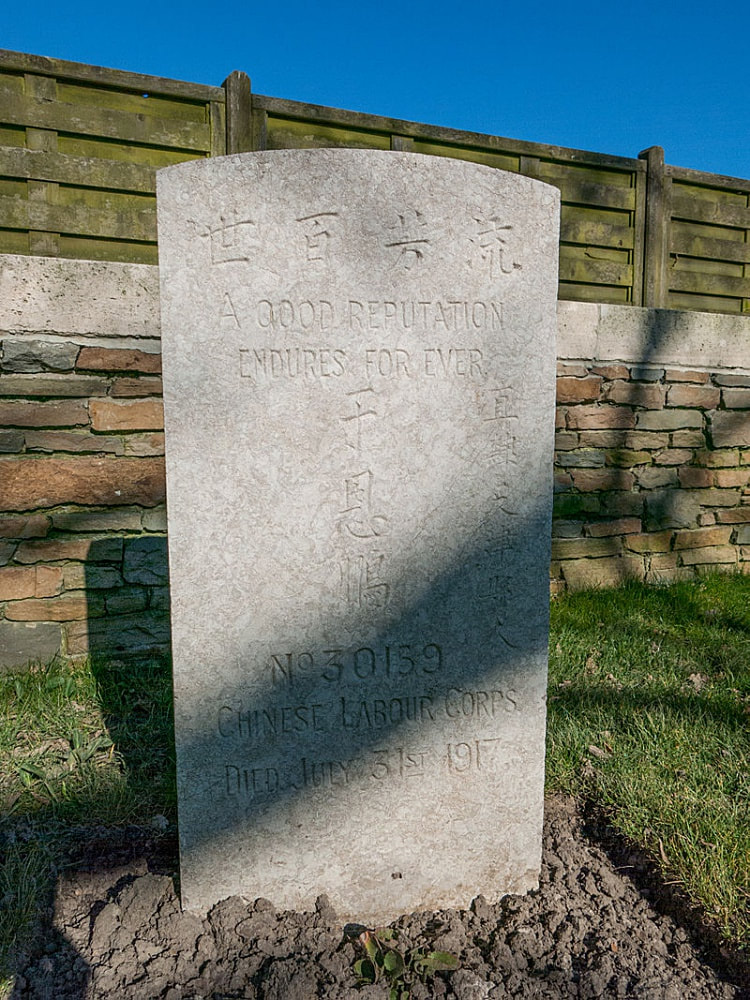

88378 Private Joseph Stedman, 117th Company, Machine Gun Corps, executed for deserton on 5th September 1917, aged 25. Plot II. F. 41. Son of Henry Patrick and Sarah Stedman, of Liverpool.

He was the first soldier from a machine-gun company to be executed. Note the terms of the inscription on his headstone — composed by his family who were seemingly unaware of, or deceived about the true cause of death. (Putkowski,pp. 189-190)

2554 Private Richard Stevenson, 1/4th Bn. Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, executed for desertion on 25th October 1916. Plot II. H. 9.

He was found to be missing after his battalion was warned to move up to the trenches on the Somme Front, & was arrested in a back-area 4 days later. At trial he gave an account inconsistent with that given on arrest a month earlier, & in the end confessed that he had lost his head & drifted away. (Putkowski, pp 121-122)

10701 Private James H. Wilson, 4th Bn. Canadian Expeditionary Force, executed for desertion on 9th July 1916. Plot II. H. 2.

An Irishman who had seen previous war service with the Connaught Rangers, he went absent to avoid service in the trenches in the Ypres Salient. (Putkowski, p 93)

He enlisted in June 1914, but because of his youth was not sent to France till Nov 1915. On 8 Aug 1916 his battalion was serving in the Ypres Salient, when at c 2200 he was seen to don his smoke helmet when the gas alarm was sounded & half an hour later was found missing when his platoon was to move forward. In the early hours of the next day, Bennett was seen c ¾ of a mile to the rear, saying that he had lost his nerve & had climbed out of the trench; & when he had returned, his company had gone.

In evidence at trial, Bennett said that he had climbed out of the trench into a shell-hole, without knowing what he was doing, & not remembering anything after that. He added that because of a previous similar occurrence he was awaiting a medical inspection — an assertion later reported to be untrue.

His record was a bad one: offences of non-compliance with orders in the UK + 2 years’ imprisonment with hard labour imposed for absence, probably from the fighting on the Somme. His CSM said that he was absolutely useless, & readily went to pieces. The CO related that most of Bennett’s 9 months with the BEF had been spent in hospital or with the transport, adding that a man of such disposition (who may not have known what he was doing) was a positive danger anywhere in the firing line, his conduct capable of giving rise to panic among his comrades. The Brigade commander recommended commutation since Bennett had apparently been too terrified to know what he was doing, but the Divisional & Corps commanders disagreed, the latter writing that: ‘Cowards of this sort are a serious danger’, & that the death penalty was provided in order to make men fear running away more than they feared the enemy. The Army commander concurred. (Corns, pp197-199,212)

12772 Private Albert Botfield, 9th Bn. South Staffordshire Regiment, executed for cowardice on 18th October 1916, aged 28. Plot II. F. 7.

He enlisted in Sept 1914, & in Sept 1916 was serving in a pioneering battalion. In the evening of 21 Sept, Bennett’s platoon were digging new trenches SE of Pozières, when at c 1915 a shell burst near by. Bennett ran away — & was seen returning to his bivouac at 0700 the next day.

At trial, he said on oath that when the shell burst he jumped into the trench & after things had quietened down he went to look for his party but was told that he was going in the wrong direction. He then sat down & slept till c 0400 — an account that varied slightly under cross-examination. Questioned by the court, Bennett said ‘I was nervous that’s why I took so long to come home’.

As to his record: in Jan 1916 he received 90 days’ Field Punishment No 1 for absenting himself from his reinforcement draft for a week; in June, another 28 days for 2 offences of absence; & in September a further 90 days, again for absence — a sentence probably still being served at the time of his final offence. The sentence of death was endorsed by all the unit commanders. (Corns, pp 200-202,212).

34595 Private James Crampton, 9th Bn. Yorks & Lancs Regiment, executed for desertion on 4th February 1917, aged 39. Plot II. B. 14 (D)

He had served 4½ months at Gallipoli when his unit was transferred to the front line in France. Crampton made off & was arrested 3 months later in Armentières — without his equipment. His plea at trial that he must have been ill led to medical examination — which availed him nothing. (Putkowski, p. 160)

8833 Private George Everill, 1st Bn. North Staffordshire Regiment, executed for desertion on 14th September 1917, aged 30. Plot II. F. 44. Son of Mrs. E. Everill, of 40, Mount Pleasant, Shelton, Hanley; husband of Mrs. L. Everill, of 7, Southampton St., Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent.

On separate occasions over c 18 months, he was convicted of using insubordinate language; wilful defiance; absence; & using threatening language. Following his punishment for the last offence, he was convicted again of wilful defiance, for which he was serving Field Punishment, when he was warned to be ready to move up for active operations. When mustered later in the day, he managed to absent himself — leaving his rifle & equipment behind — but was found & arrested the next day. At trial, the accused questioned no witness & made no statement of his own. (Putkowski, p 193-194)

16120 Private John W. Fryer, 12th (Bermondsey) Bn. East Surrey Regiment, executed for desertion on 14th June 1917, aged 23. Plot II. D. 14.

He deserted when serving under a suspended sentence of 2 years’ imprisonment imposed for a previous offence of Desertion. (Putkowski, pp 174-175)

15605 Private Frederick C. Gore, 7th Bn. The Buffs ( East Kent Regiment), executed for desertion on 16th October 1917, aged 19. Plot II. J. 34.

On 10 Aug 1917, when serving near Ypres, he was warned for parade, but soon went missing. Gore was next heard of on 19 Aug, when he presented himself at Boulogne, saying that he was a deserter from Etaples. He was wearing uniform, & gave his correct name & regiment.

At trial, his written statement said that he had deserted ‘because I cannot stand the strain of the shell-fire owing to the very bad state of my nerves’; & that before he came to France, he had been rejected for service abroad because of his nerves. He added that the MO had said that nothing could be done for him. When questioned, he gave some detail: he had spent 5 weeks in hospital for shell-shock, before being returned to his unit about mid-June 1917; & that he had ‘another shaking up when we were holding the line at the end of July’, after which he was examined only by a stretcher-bearer, & sent back to duty.

His conduct sheet showed 4 offences committed between Mar 1916 & July 1917, one of which related to an absence in Apr 1917, when his Lance Corporal’s stripe was taken away. (Corns, pp. 323-324)

416874 Private Come LaLiberté, 3rd Bn. Canadian Expeditionary Force, executed for desertion on 4th August 1916, aged 25. Plot II. H. 3. Son of Luger and Eugenie Hamel LaLiberté, of 170, St. Ferdinand St., Montreal.

He deserted when his unit was billeted within the Ypres Salient, & was executed in front of his battalion. (Putkowski, pp. 98-99)

2974 Private Bernard McGeehan, 1/8th Bn. King’s Liverpool Regiment, executed for desertion on 2nd November 1916. Plot II. D. 9.

His battalion having suffered considerable losses in attack, he deserted from the renewed action. (Putkowski, p. 128)

23686 Private James S. Michael, 10th Bn. Cameronians, Scottish Rifles, executed for desertion on 24th August 1917. Plot II. H. 24.

He deserted to avoid fighting in the Ypres Salient. (Putkowski, p. 187)

7429 Private Herbert Morris, 6th Bn. British West Indies Regiment, executed for desertion on 20th September 1917, aged 17. Plot II. F. 45. Son of William and Ophelia Morris, of Riversdale P.O., St. Catherine, Jamaica.

A Jamaican, he had enlisted in Dec 1916 in a recruitment drive in the West Indies, & arrived in France in Apr 1917. After brief acclimatisation, the battalion moved to communications duties in the Ypres area. On 20 Aug 1917, Morris went missing from a working party, turning up the next day at the St Martin rest camp at Boulogne, saying that he had been sent there by mistake & was on his way to Le Havre. As he had no rifle, equipment or leave pass, he was arrested.

At trial on 7 Sept, Morris — who was unrepresented — made an unsworn statement, saying that he could not stand the sound of the guns, & that the doctor that he had seen on 19 Aug gave him no satisfaction. Despite this defence, no medical examination was ordered, nor was the doctor called to testify.

2 officers gave evidence that Morris had never given any trouble, & worked willingly, but it further appeared that Morris had gone missing on 16 July, being found in Boulogne the next day — for which 14 days’ Field Punishment No 1 had been imposed. (Corns, p. 300)

G/11296 Private William Henry Simmonds, 23rd Bn. Middlesex Regiment, executed for desertion on 1st December 1916, aged 23. Plot II. E. 9. Son of William and Emily Simmonds, of 18, Sidney Terrace, Bedfont Lane, Feltham, Middlesex.

Deserted from the Somme Front. (Putkowski, p 140)

88378 Private Joseph Stedman, 117th Company, Machine Gun Corps, executed for deserton on 5th September 1917, aged 25. Plot II. F. 41. Son of Henry Patrick and Sarah Stedman, of Liverpool.

He was the first soldier from a machine-gun company to be executed. Note the terms of the inscription on his headstone — composed by his family who were seemingly unaware of, or deceived about the true cause of death. (Putkowski,pp. 189-190)

2554 Private Richard Stevenson, 1/4th Bn. Loyal North Lancashire Regiment, executed for desertion on 25th October 1916. Plot II. H. 9.

He was found to be missing after his battalion was warned to move up to the trenches on the Somme Front, & was arrested in a back-area 4 days later. At trial he gave an account inconsistent with that given on arrest a month earlier, & in the end confessed that he had lost his head & drifted away. (Putkowski, pp 121-122)

10701 Private James H. Wilson, 4th Bn. Canadian Expeditionary Force, executed for desertion on 9th July 1916. Plot II. H. 2.

An Irishman who had seen previous war service with the Connaught Rangers, he went absent to avoid service in the trenches in the Ypres Salient. (Putkowski, p 93)

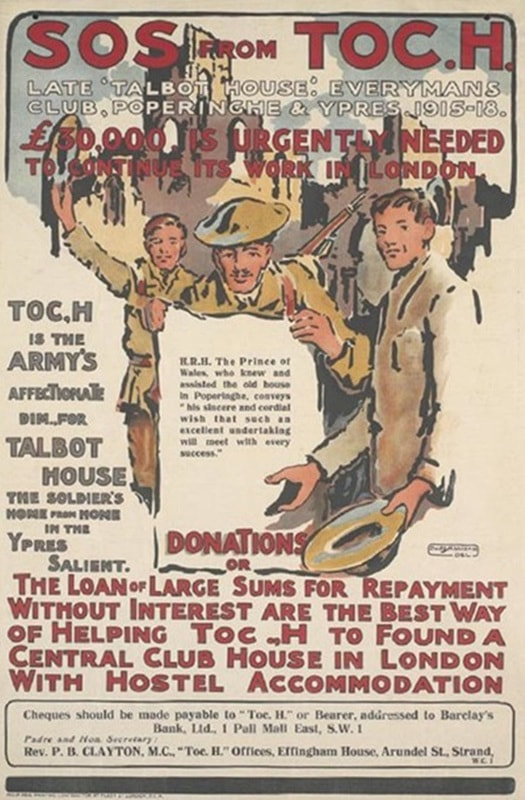

TOC H was a rest centre for British soldiers of all ranks stationed in the Ypres sector in Flanders. It was the idea of a young army chaplain, the Reverend ‘Tubby’ Clayton, who established the centre in ‘Talbot House’ [TOC H in Army telephone jargon] in the Belgian town of Poperinge. Talbot House offered British troops a respite from the Front and an opportunity to develop and examine their understanding of the Christian faith. After the war former soldiers from Talbot House continued the work of TOC H as a civilian charity, establishing hostels and local branches to promote the Christian faith through community orientated work programmes. The work of TOC H continues to this day as an international Christian organisation involved in various charitable and social projects.

© IWM (Art.IWM PST 10992)

© IWM (Art.IWM PST 10992)